“Atoms and void and nothing else.”

contents

- support the china channel: fund original translations from Chinese!

- little smarty visits the future: classic 70s chinese sci fi

- jiang shigong’s clash of civilizations: fukuyama or huntingdon, pick one

- unending capitalism: an interview with karl gerth

- this week in history: 1711, 1881, 1898

- colophon: reading, writing, listening

support the china channel: fund original translations from Chinese! (permalink)

Three years ago, I had the honor of helping launch the LARB China Channel. (If you are looking for someone to thank for the fluorescent pink theme & chop, look no further…) Having since stepped away from day-to-day operations, I still miss getting to translate stuff like this:

https://chinachannel.org/2017/09/27/lu-xun-demon-hunter/

Or share translations of stories published elsewhere:

https://chinachannel.org/2017/11/03/han-song-finished/

I still write the occasional review, but it’s just not the same (although astute readers will notice a theme):

https://chinachannel.org/2020/05/15/lovecraft/

If you’d like to support the excellent work of other aspiring translators of Chinese short stories and creative non-fiction, the Channel has a set up a Patreon account which (when I last checked) was (just 3 bucks!) short of $100 dollars a month in pledges:

https://chinachannel.org/2020/08/31/patreon-translations/

I know, I know. Everyone seems to be passing the hat these days. But on the other hand, if you’re frustrated with the how little coverage Chinese-language writers get in English, here is a concrete way to make sure that more of them get to be heard.

[blatant self-promotion over!]

little smarty visits the future: classic 70s chinese sci fi

(permalink)

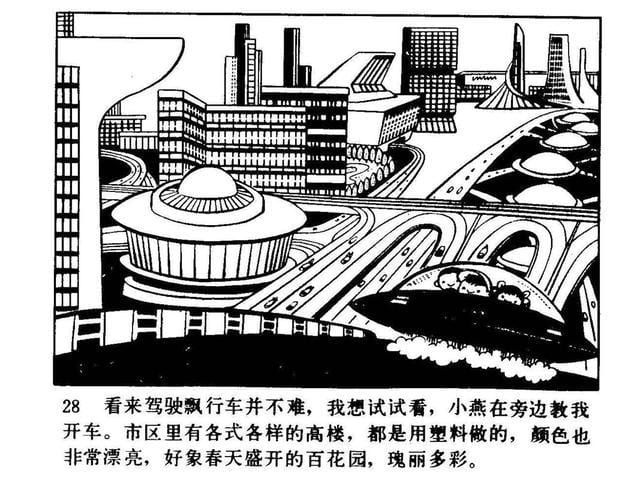

Very excited to see that the Modern Chinese Literature and Culture Resource Center has posted a translation of a 1980 comic book adaptation of Ye Yonglie’s 叶永烈 classic science fiction yarn, Little Smarty Visits the Future 《小灵通漫游未来》(thread)

https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/little-smarty-travels-to-the-future/

This week they posted part II, a new essay on the story by Lena Henningsen:

https://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/little-smarty-intro/

Ye passed away May of this year, so the timing is bittersweet. I’d been planning to do a translation of this comic for ages, so I’m glad that Henningsen and her students (Adrian Ewald, Lars Konheiser, Elena Mannich) took this on — I only wish that Ye was still here to see it.

As Henningsen explains, Ye wrote with the story in the mid-1960s, but couldn’t actually publish it until 1978, two years after the (unofficial) end of the Cultural Revolution.

In her essay, Henningsen traces the history of science fiction in the PRC, from the first 1950s in the 1950s, to the second wave of the late 1970s (to which Smarty belongs) and the third wave of last decade.

She also discusses lianhuanhua (comic books), which were “used as a tool to promote knowledge or inculcate ideology among young readers […] [and] can be read as illustrations of reality or as illustrations of imagined realities”.

In the final section of her essay, Henningsen compares the 1980 comic book adaptation with the original 1978 illustrated novel, and also a second comic book adaptation — there were several — to tease out some significant details in the story.

She also touches on the concept of 2nd wave Chinese science fiction as “lobby literature”, an idea which was suggested by Rudolph Wagner (another great who left us too soon) in his seminal essay included in this collection:

https://archive.org/details/aftermaochinesel0000unse

In his essay, which was written in 1983, Wagner argues that Chinese science fiction in the late 70s and early 80s was designed to “lobby” for the special treatment of scientists and other intellectuals in the wake of the Cultural Revolution.

He makes a good case for it, but I’m not sure I’m entirely convinced — there are some pretty wild stories from the 2nd wave. Hopefully more of them will be translated and made available to be read online like this

Also, I highly recommend bookmarking the Politics of Reading (READCHINA) website, where a gigaton of PRC popular culture is set to appear on your ansible in the very near future:

jiang shigong’s clash of civilizations: fukuyama or huntingdon, pick one (permalink)

Last week David Ownby posted a new translation of a recent (very long) essay on Sino-US relations by the legal and political philosopher Jiang Shigong 强世功 to the Reading the Chinese Dream site:

https://www.readingthechinadream.com/blog/jiang-shigong-on-sino-us-relations

(thread)

Having 个人利益 when it comes to Sino-US relations, I was curious to see what he had to say.

In his introduction to the translation, Ownby describes Jiang as an “important spokesman for China’s New Left, and a major apologist for the Xi Jinping regime.” From his essay, I would say that is a fair description.

Accordingly, Ownby notes that he doesn’t personally find Jiang’s “triumphalist” commentary particularly convincing, but suggests that Jiang is worth reading because of his closeness to the leadership.

The essay is largely framed around two concepts, which Jiang treats as mutually exclusive: On the one hand, Francis Fukuyama’s reading of liberal democracy as the “end of history”, and on the other, Samuel P. Huntington’s prediction of a 21st century “clash of civilizations.”

For Jiang, Huntington provides a “realist’s heartfelt advice to the liberal idealist,” because unlike Fukuyama’s “normative analysis,” his analysis is “the analysis of political history.”

From here Jiang discusses why “in Huntington’s view, the first question in politics is not the form of the government, but instead the question of how to establish stable political authority only after which can one impose political order and avoid political decay.”

In this reading, Huntington (who famously credited “democratic distemper” with the US defeat in Vietnam), allows Jiang to advance the claim that “being pro-America brings political decay, while leaving behind political decay requires opposing America.”

Earlier in the essay, Jiang argues that that “politics is the art of winning hearts and minds” because “what people need is not just an increase in wealth; much more important is to renew our belief in how to act as people, in social norms, and in life ideals.”

Ownby suggests that Jiang’s use of Huntingdon is a strategic appeal to liberals, “a rallying cry to Chinese intellectuals to surrender their American dreams and come back to the motherland. Huntington said it was okay.”

In his conclusion, Jiang writes, “only if we gradually develop a stable and desirable lifestyle will other countries wish to emulate our experience and our lifestyle, at which point we can consciously or unconsciously shape the world.”

He seems to be reassuring intellectuals that if China goes its own way, sooner or later the world will follow: “It’s like dealing with the pandemic. Whether they wanted to or not, Western countries finally did like we did, put on their masks and practiced social distancing.”

The problem (to my mind) with Jiang’s argument is that he frames the choice facing China as an either/or proposition. Fukuyama or Huntington, pick one! It isn’t obvious to me, however, that either of these choices is the right one.

Fortunately, it’s not up to me, and equally fortunately, Jiang’s opinions are by no means the only ones in currency within or without China at the moment.

As a follow-up, Ownby suggests two recent essays also available in translation on Reading the Chinese Dream. The first is by Yuan Peng, based in Beijing:

https://www.readingthechinadream.com/yuan-peng-coronavirus-pandemic.html

And the second, which is more critical, is by Deng Yuwen, who is (presumably) based outside of China:

https://www.readingthechinadream.com/deng-yuwen-chinese-statism.html

unending capitalism: an interview with karl gerth (permalink)

Just up on the New Books in East Asia podcast, Sarah Bramao-Ramos interviews Karl Gerth on his latest book, Unending Capitalism: How Consumerism Negated China’s Communist Revolution (Cambridge University Press, May 2020):

In the interview, Gerth discusses his overarching research project, to write a “sweeping history of consumerism in 20th century China.” He describes his first book, on the origins and political uses of Republican-era consumerism as more of a traditional scholarly monograph:

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674016545

(This book was a big inspiration for me when I was writing my MA thesis on cartoonists as cultural entrepreneurs in 1920s Shanghai.)

Whereas his second book, on consumerism in the contemporary PRC, was written with a general audience in mind:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780809026890

This is Gerth’s third book, and it takes aim at consumerism in “the mysterious middle” — the period from the Communist victory in 1949 up to early 1980s (known in China as ‘Reform and Opening’).

As Gerth explains in the interview, most historians of modern China who look at the PRC have focused on production, given the Party’s emphasis on expanding industrial capacity (particularly military technology) and modernizing agriculture.

In his book, Gerth argues however that the endless rhetorical appeals to eliminating capitalism and building socialism obscure the development of what he calls “state capitalism” and its corollary, “state consumerism.”

In the first chapter he discusses his terminology in more detail.

In the second chapter of the book Gerth draws on his previous work on the Republican era to discuss how the Communists expanded already existing institutions to facilitate capital accumulation in place of socialist transformation in the cities and the countryside.

In the third chapter he discusses Soviet influences on state consumerism, in the form of the officially-sanctioned craze for Soviet fashions, cultural products, and goods.

In the fourth chapter Gerth considers the promotion of “social consumption” and frugality in advertisements, propaganda posters, and films, while in the fifth chapter he explores the service sector and retail distribution.

In the sixth chapter, he looks at the contradictory role consumerism played in the Cultural Revolution, when Red Guards found themselves acting out fantasies of bourgeois consumption.

This discussion continues in the seventh and final chapter, where Gerth looks at the underground economy of Mao badges, which he sees as a “quintessential example of the self-generating and compulsive nature of consumerism.”

It was published by Cambridge University Press in May of this year — for those of us lucky enough to have institutional access, you can read it online here:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/unending-capitalism/5483015D567CDB2100F20AF0F4E499C0

If you want to buy a copy, it’s actually relatively affordable for a history book ($25 paperback / $20 ebook):

this week in history (permalink)

Sept 22 1898 #122yrsago – A coup d’etat led by supporters of Empress Dowager Cixi against the Guangxu Emperor ends the Hundred Days’ Reform 戊戌变法

[James Carter has also written about this for his Sup China column: https://supchina.com/2020/06/26/when-chinas-reformers-believed-anything-was-possible-100-days-in-1898/]

Sept 25 1711 #309yrsago – birth of the fourth son of the Yongzheng Emperor, who would reign as the Qianlong Emperor from 11 October 1735 to 8 February 1796, and Retired Emperor until his death in 1799

September 25 1881 #139yrsago – birth of Lu Xun 鲁迅 (d. 1936), Chinese short story writer, essayist, and social critic

colophon (permalink)

h/t: chinachannel.org, READCHINA, reading the chinese dream

reading: walkaway by cory doctorow [near future post-scarcity anarcho-syndicalism]

writing: my PhD dissertation, Constructing the Future 未来建设, a history of chinese comics in the early reform era (1978-1983)

this week’s progress: 1,111 words (32,412 total) #weeklywords

listening: Mirah and the Black Cat Orchestra – To All We Stretch The Open Arm

quotations and images public domain or fair use unless otherwise indicated

everything else CC BY 4.0 / free to share & adapt w/ attribution