The following is based on a presentation I gave for the 2017 Association of Asian Studies annual conference in Toronto as part of the panel Materia Manhuanica: Reading Chinese Cartoons on March 16, 2017. Funding for this panel was generously provided by the Huang Yao Foundation, with Eileen Chow serving as discussant. Additional revisions were suggested by my co-panelists John Crespi, Madeline Gent, and Orion Martin. Finally, I am indebted to Barbara Mittler, whose March 6, 2017, seminar “A King’s Two Bodies? Mao’s Death and his Legacy” at UBC got me thinking about how China’s “transformative nationalism” changed under Mao and the CCP, and what this might tell us about Zhang Shijie’s Boxer comics, and their eventual suppression.

I want to begin first by thanking Mississauga people of the Ojibwe Anishinaabe First Nation on whose ancestral lands we are hosting this event today. For those of you who are just visiting Canada for the first time, this might seem a little odd, but I encourage you, especially in the really, frankly, pretty frightening times we find ourselves, I encourage you to think about this question of ownership. Who does the land really belong to and where do we all come from? Where do our stories come from and who do they belong to? I think these are questions which we are going to talk about more during tonight’s panel, and also during our question and answer session.

Niubizi and John Crespi at the AAS 2017 Materia Manhuanica panel.

Niubizi and John Crespi at the AAS 2017 Materia Manhuanica panel.

Secondly, I wanted to thank the Huang Yao Foundation for sponsoring this panel. If you haven’t heard of them yet, the Huang Yao Foundation is an amazing organization, which was founded by Carolyn Huang, Huang Danrong 黄丹蓉 and the Huang family in 2001, with the goal of preserving their grandfather’s legacy as a cartoonist, a painter, and a scholar. Over here, on our sign, you can see Niubizi, or ‘Willie Buffoon’ as he was known in English. The Huang Yao Foundation has been really tireless in collecting information on Huang Yao’s career, and the careers of his peers, and they have a lot of resources to share with Chinese comics scholars. I think almost everyone on the panel today has worked with them in some capacity over the years. So I encourage you all to check them out online at huangyao dot org, and also to keep an eye out for some of the publications and other projects which will be coming down the line over the next couple of months.

Finally, I wanted to thank all of you for being here today. I know there are always a lot of demands on people’s time during AAS, and it really means a lot to us that you were willing to stop by and geek out on Chinese comics for a bit. I know that comics sometimes get a bad rap, and comics scholars are pretty notorious for spending a lot of time and energy on justifying their interest in what is, aside from being physically ephemeral, also pretty crude art form. Even if comics aren’t nearly as “declassee” as they once might have been, thanks to the material turn, I think there is still a big question that looms over any discussion of comics, which is, “Why comics?” Because there really is something that compels comics fans (like all of us here) to really “stand by our man” [hua].

Okay, no more bad puns, I promise!

So one of the things I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is being thankful and mindful of the spaces we inhabit. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but also because it brings up this question of belonging. ‘Belonging’ is one of those great words that goes both ways—in the sense of belonging to a place, and places belonging to us.

Nanabozho piles muskrat’s earth on the shell of a turtle while beaver and otter look on in “The Creation of the World” Daphne Odjig (b. 1919, Potawatomi and Odawa First Nation), 1972.

Nanabozho piles muskrat’s earth on the shell of a turtle while beaver and otter look on in “The Creation of the World” Daphne Odjig (b. 1919, Potawatomi and Odawa First Nation), 1972.

So here we have this great mural by Daphne Odjig from the 1970s, which depicts the trickster god Nanabozho piling mud on the back of turtle to create the world. Over here you have beaver, and muskrat, who for modern viewers might bring to the mind the fur trappers, who formed the vanguard of Western imperialism in North America, and particularly here in Canada. So there’s one reading of this piece, which is basically a straight reading, as being about a creation myth, and another one, which is more subjective, but gets into a different kind of creation myth—the creation of Canada as a nation.

Now, I don’t know what Odjig would say about her painting, or if she would agree with this sort of reading, I did find this quote from her from 1968 that I think speaks to what I want to talk about today:

“If you destroy our legends you destroy our soul.”

– Daphne Odjig, 1968 (from Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair’s introduction to Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water)

And that’s really a great launching off point for talking about Zhang Shijie, and his ‘folk’ stories set during the Boxer Uprising at the turn of the 20th century, but actually collected and edited (pretty heavily in some cases) and published towards the end of the 1950s and up to the mid-1960s. What’s interesting about these stories, one collection of which was called 义和团传说故事 or ‘Boxer Legends,’ is that they are mostly remembered today for the comic book and cartoon adaptations.

There were actually two collections of lianhuanhua or ‘linked picture books’ that came out in 1959 (just two years after Zhang Shijie’s first collection of folktales was published), one from Tianjin Fine Arts Press 天津美术出版社 and the other from People’s Fine Arts Press 人民美术出版社 in Beijing. Originally I thought one was a reprint of the other, but it turns out they were two completely separate adaptations. Zhang Shijie himself was from Anci county, which is now part of Langfang city in Hebei, just about smack dab in the middle of where his two publishers were located. So I guess he was hedging his bets?

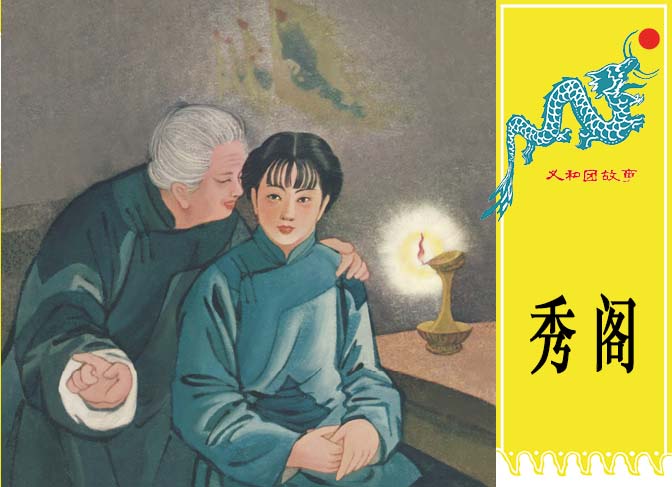

Now, as you can see (the full list of comics is available here), there were a lot of repeats: Xiu Ge (which I like to call ‘lady boxer’, since it’s about an educated woman who joins the Boxers):

Xiu Ge: Lady Boxer 《秀阁》 Adapted by Cheng Hua 程华 and Wu Chao 吴超, illustrated by Zhu Guangyu 朱光玉. August, 1959,F60,62 pages,64,000.

Xiu Ge: Lady Boxer 《秀阁》 Adapted by Cheng Hua 程华 and Wu Chao 吴超, illustrated by Zhu Guangyu 朱光玉. August, 1959,F60,62 pages,64,000.

Xiu Ge: Lady Boxer 《秀阁》 Chen Pingfu 陈平夫, illustrated by Wang Qimin 王企玟. April, 1960. F60, 62 pages, 54,500.

Xiu Ge: Lady Boxer 《秀阁》 Chen Pingfu 陈平夫, illustrated by Wang Qimin 王企玟. April, 1960. F60, 62 pages, 54,500.

Hong Dahai (a kind of Paul Bunyan figure who, you guessed it, joins the Boxers):

Hong Dahai 《洪大海》 Cheng Hua 程华 and Wu Chao 吴超, illustrated by Zhang Bocheng 张伯诚. September, 1959, F60, 57 pages, 80,000.

Hong Dahai 《洪大海》 Cheng Hua 程华 and Wu Chao 吴超, illustrated by Zhang Bocheng 张伯诚. September, 1959, F60, 57 pages, 80,000.

Hong Dahai 《洪大海》 Yang Xi, 杨犀, illustrated by Zhao Baishan 赵白山. January, 1960, F60, 54 pages, 88,000.

Hong Dahai 《洪大海》 Yang Xi, 杨犀, illustrated by Zhao Baishan 赵白山. January, 1960, F60, 54 pages, 88,000.

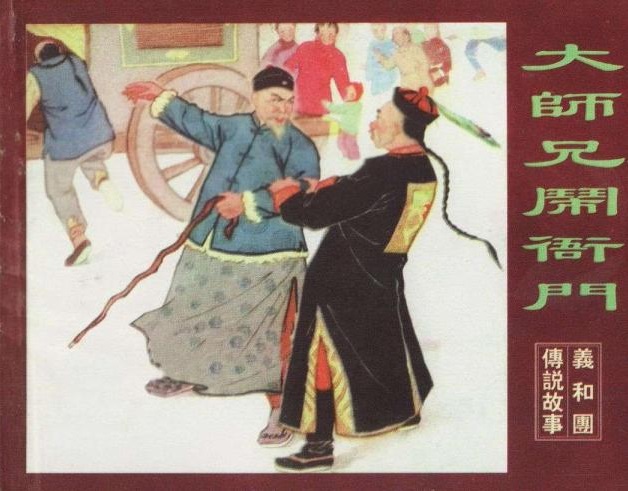

And Master and Disciples Attack the Yamen 大师兄闹衙门 (which puts a sort of wuxia, Fists of Fury spin on a Boxer story), among others:

Master and Disciples Attack the Yamen 《大师兄闹衙门》 Cheng Hua and Wu Chao, illustrated by Zong Jingcao 宗静草. August, 1959, F60, 78 pages, 73,000.

Master and Disciples Attack the Yamen 《大师兄闹衙门》 Cheng Hua and Wu Chao, illustrated by Zong Jingcao 宗静草. August, 1959, F60, 78 pages, 73,000.

Master and Disciples Attack the Yamen 《大师兄闹衙门》 Lai Yongfen 来涌芬, illustrated by Wang Cunren 王存仁. May, 1960, F60, 69 pages, 81,000.

Master and Disciples Attack the Yamen 《大师兄闹衙门》 Lai Yongfen 来涌芬, illustrated by Wang Cunren 王存仁. May, 1960, F60, 69 pages, 81,000.

There was also even some overlap with artists: Zhu Guangyu 朱光玉 worked on four books for People’s Art, and one book for Tianjin.

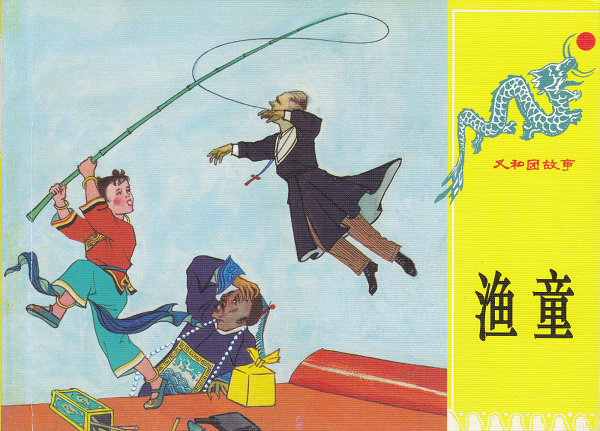

Now, the book we are going to talk about today is called Fisher Boy, which was only adapted into a lianhuanhua (as far as I’m aware) by People’s Art. It was the second in their series, and came out in July, 1959.

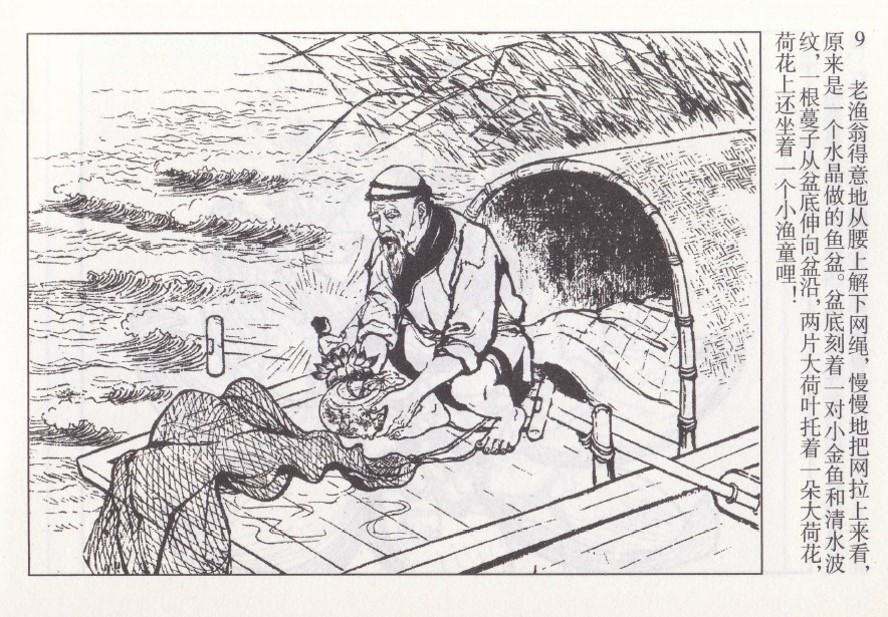

The story is pretty simple: One day a fisherman finds a magic fishbowl made of quartz, with a lotus growing out of it.

Inside the lotus is a ‘little fisher boy’ 小渔童:

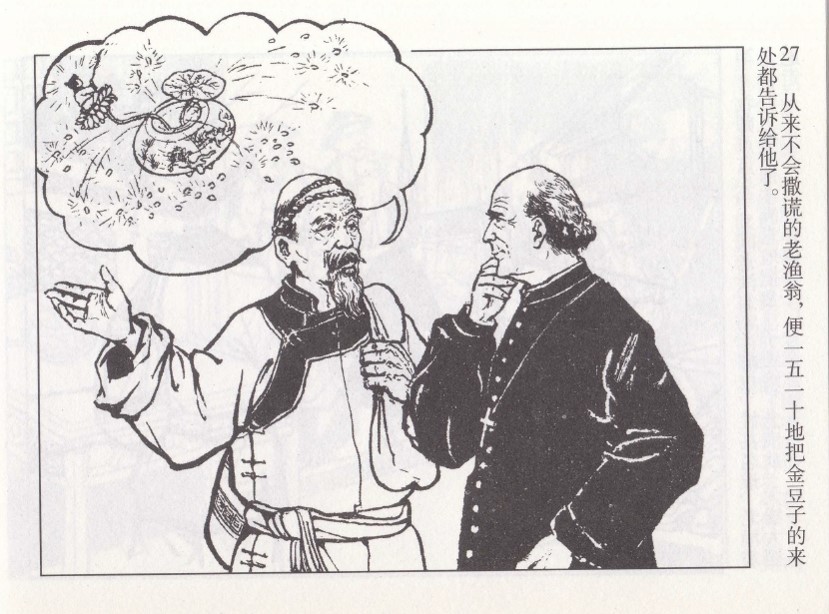

The Fisher Boy turns out to have a magic power: When he catches goldfish in his bowl, the beads of water which fly off turn into ‘golden beans.’ When the old fisherman goes into town to sell his golden beans, he makes the mistake of telling a missionary (who is called a priest 牧师 in the story) about where they came from.

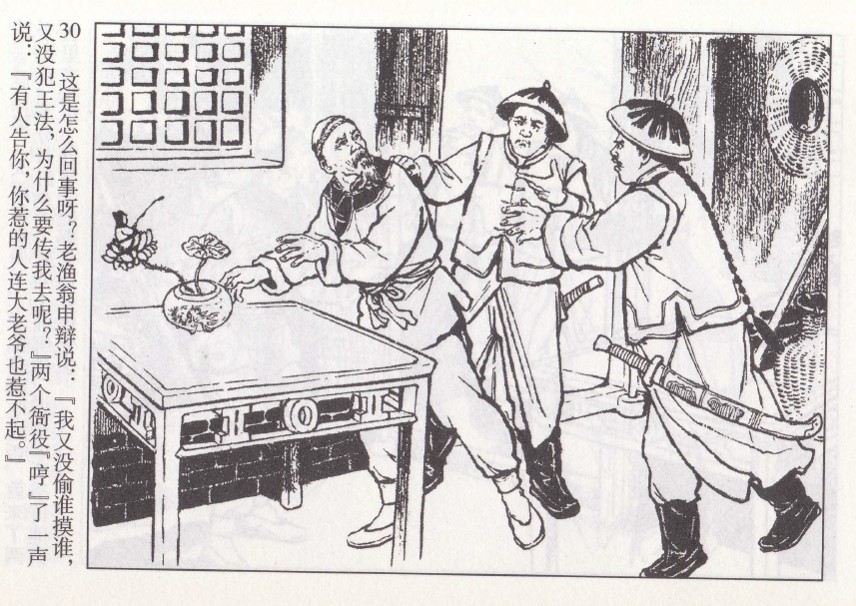

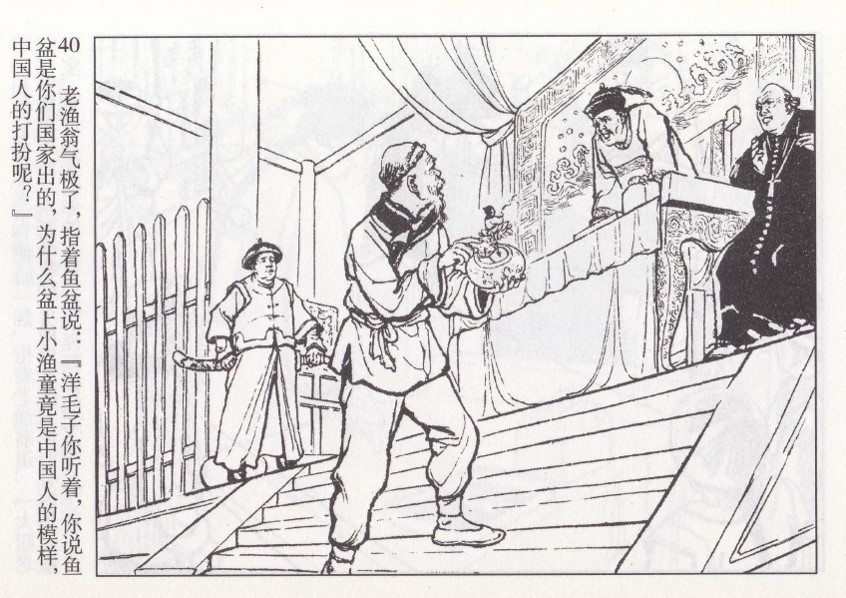

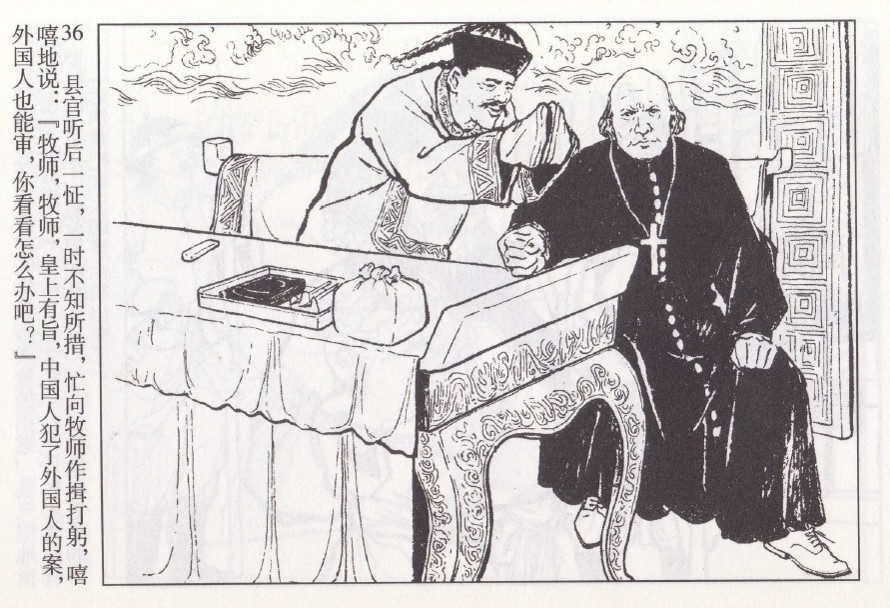

The missionary, of course, is in cahoots with the local yamen, who send their lackeys to arrest the old fisherman and take away his magic fishbowl, telling them that the fisherman stole it from him:

The fisherman says (literally) you’re full of shit 滿嘴噴糞【you’re like a yawing dung beetle 屎殼螂哈欠】 but here we can see the power dynamic between the peasant fisherman and missionary: we’re literally looking up at him.

And the Qing official, the county head actually, is kowtowing to the missionary:

And the fisherman says, “Okay so let’s say this is yours, why does the fisher boy look Chinese then?”

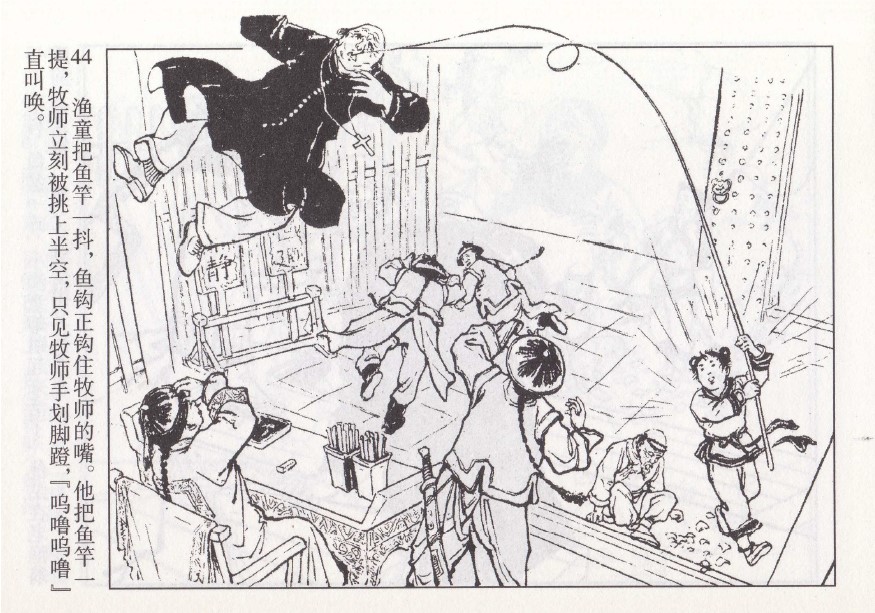

So the missionary is exposed as a fraud, but the Qing official is so pissed off that he tells his guards to beat a confession out of the old fisherman. Just when all seems lost though….

…the quartz fishbowl gets smashed and the Fisher Boy jumps out and strings up the missionary, who he then throws into the next county:

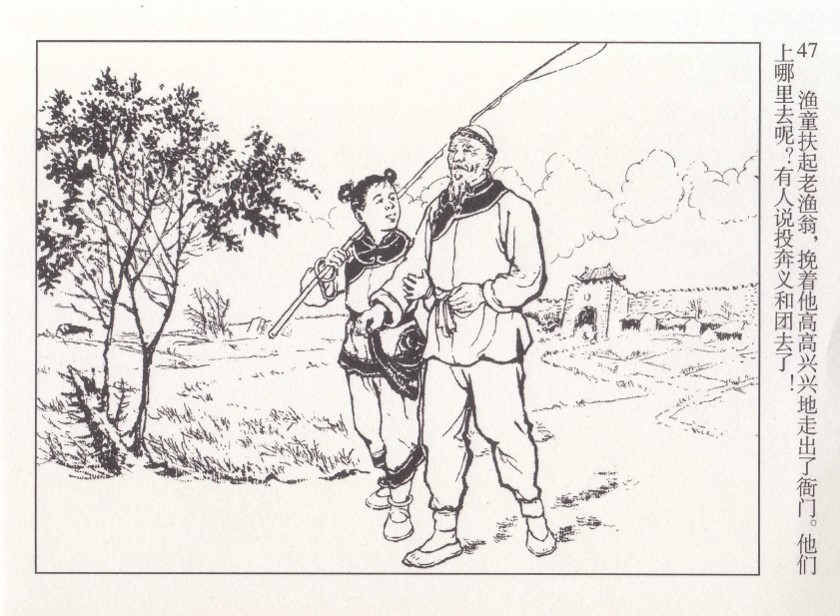

And of course, fisherman and fisherboy live happily ever after. Well, actually, like most of these stories, happily ever after means ‘they joined the Boxers’ to fight the evil imperialists.

So there a couple of things that I think are really interesting about this story, and really, all of Zhang Shijie’s stories. The first is, of course, the timing. The late 1950s and early 1960s are a fascinating time in the PRC, because there is this brief window of possibility where a lot of things that hadn’t really been allowed during the first decade of the PRC (and certainly not at Yan’an during the war) started getting allowed again: ghost operas, comedies, and lots of cartoons.

“Braving Wind and Wave, We Reveal Ourselves to Be Sages” 乘风破浪 各显神通1

“Braving Wind and Wave, We Reveal Ourselves to Be Sages” 乘风破浪 各显神通1

Politically, we have the Hundred Flowers movement in 57, the Great Leap Forward from early 58 to late 59, when Mao stepped down as chairman of the PRC (but stayed on as chairman of the CCP), and then the Cultural thaw until the Socialist education movement of 1963 and Cultural Revolution of 66.

1959 was also the year that the Sino-Soviet split really become irrevocable, even though things had been getting worse since Khrushchev’s secret speech denouncing Stalin in 57. Culturally, I think the Boxer comics represent a sort of ‘religious iconography’ of Maoism, to go along with the radical new economic, social, and agricultural policies that Mao was trying to put into place—somewhat like how Taoist iconography was being adapted for posters like this one, which was riff on Yan Liben’s 阎立本 “Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea” 《八仙过海》.

Yan Liben 阎立本 “Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea” 《八仙過海圖》2

Yan Liben 阎立本 “Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea” 《八仙過海圖》2

So here we have the original, or at least a convincing forgery which is said to have been painted in the Tang. The only problem with that of course is that the Eight Immortals don’t show up in the literature until the Yuan…

Anyways! This adaptation of iconography is ongoing, like in this more recent riff on the Eight Immortals:

…by the internet artist, Xia Ah, who specialized in spoofs 惡搞 of classic paintings. (He’s actually the one who tipped me off about the wonky dating on the original Eight Immortals painting.)

So this isn’t nearly as off topic as it might seem, I swear. Because superheroes really are the equivalent of gods, or immortals, today, so I think Xia Ah is really on to something here with his painting. I think it explains a lot about the popularity of the Avengers franchise in China, and also the Transformers, in that these films really tap into long running tradition in China of heroic legends or myths.

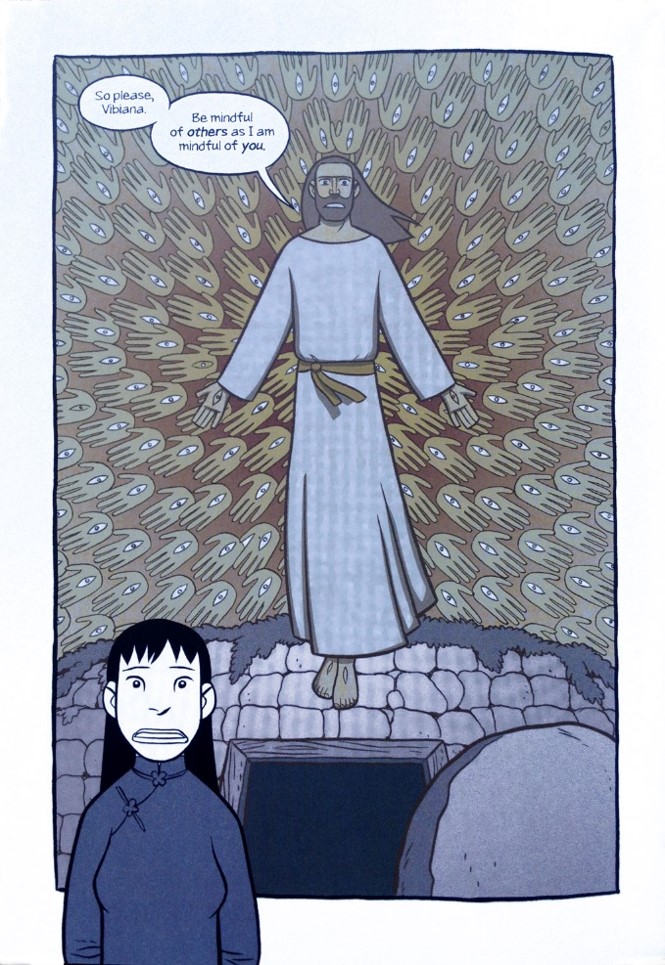

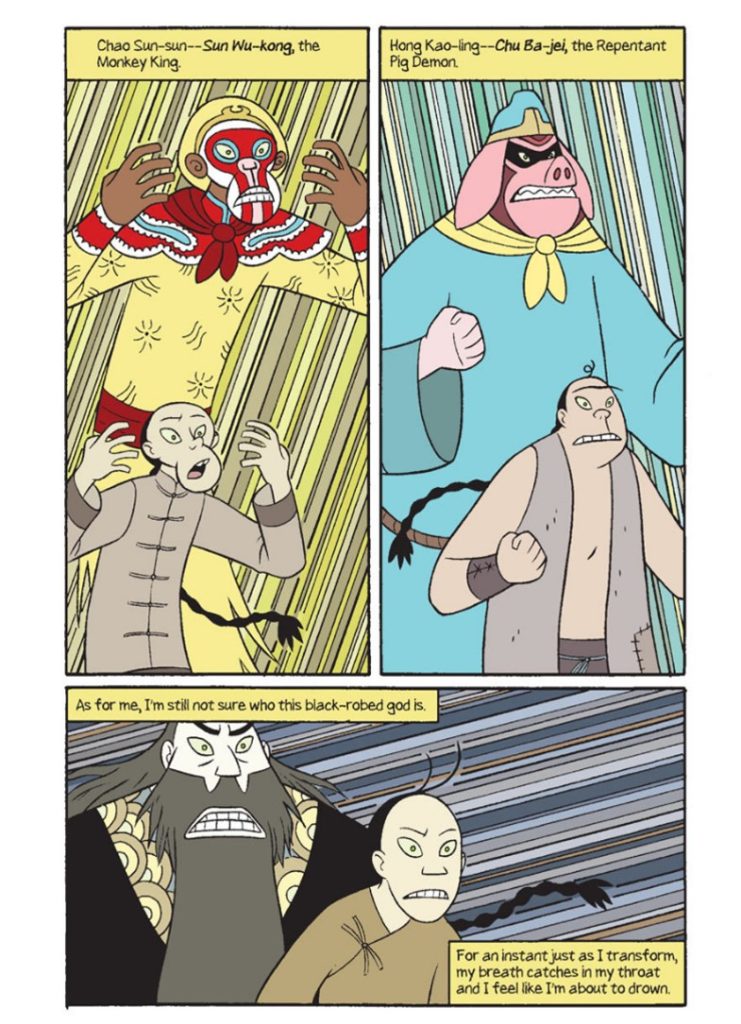

Gene Luen Yang’s depiction of the Boxer spirit possession ritual intentionally resembles American superhero comics and Japanese manga

Gene Luen Yang’s depiction of the Boxer spirit possession ritual intentionally resembles American superhero comics and Japanese manga

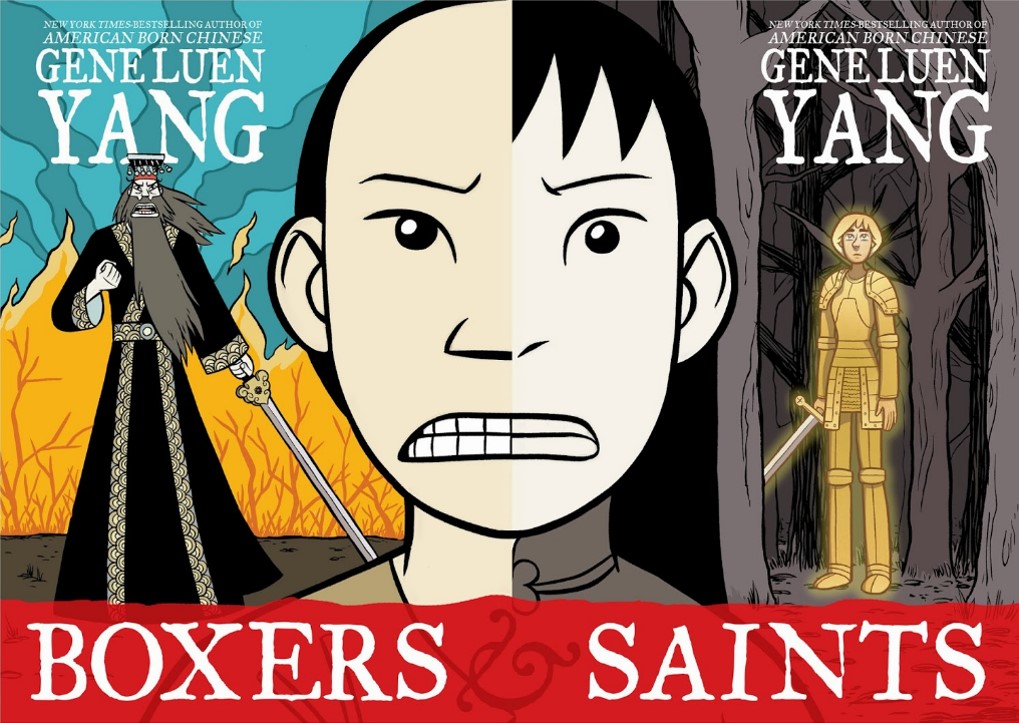

Gene Luen Yang made this connection of Boxers to superheroes explicit in his recent graphic novel Boxers and Saints. In interviews, he has said that he drew on Esherick’s 1987 book, Origins of the Boxer Uprising which describes a lot of the mythology that the Boxers actually drew on for their transformation rituals—burns bits of paper spells and eating them to become superhuman gods, impervious to bullets and blades.

And this narrative of transformation is something that I think really defines the zeitgeist of the PRC during the first decade of “New China.” So here we have the Chinese version of the Internationale, first translated by Qu Qiubai, and later revised by Xiao San in 1962. The Internationale, of course is the defacto anthem of the PRC (minus a few of the more incendiary stanzas). But what remains, and the lines most of us know, is this bit about slaves becoming masters:

| Rise up, slaves, hungry and cold! Rise up, oppressed people of the world! The blood of my chest boils over,We must fight for truth!Cast off the old world,Slaves, rise up, rise up!Do not say we have nothing,We will be the masters of the world! |

起来,饥寒交迫的奴隶!

起来,全世界受苦的人! 满腔的热血已经沸腾, 要为真理而斗争! 旧世界打个落花流水, 奴隶们起来,起来! 不要说我们一无所有, 我们要做天下的主人! |

A very Boxer like transformation, I think.

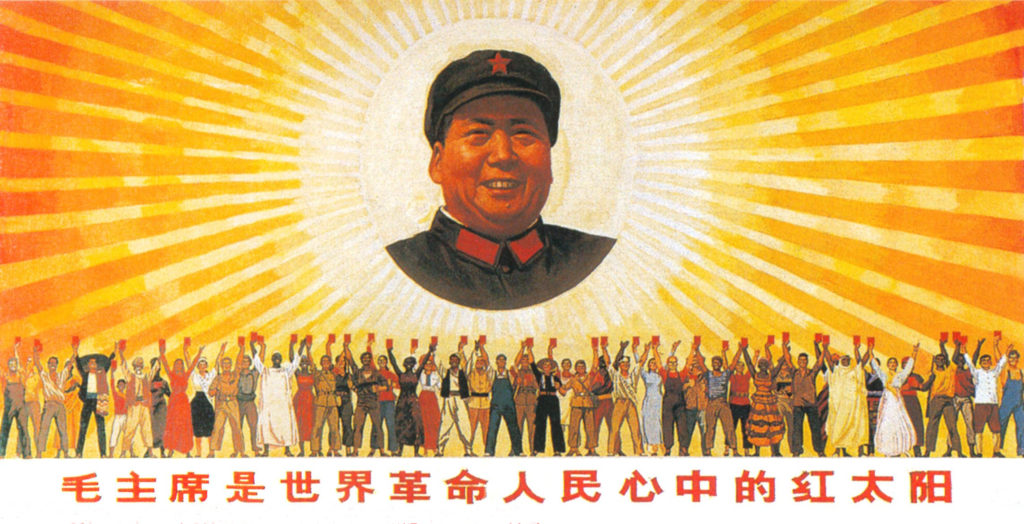

The really fascinating thing about this “transformative nationalism” is that under the CCP it becomes sublimated under the figure of Mao. This isn’t even something I really thought about until I went to Barbara Mittler’s talk the day before yesterday at UBC, on her ongoing project on Mao’s body, particularly after death, and comparing his body to that of Gandhi, and their respective relationships to the body politic. But for my project, I’ve been thinking a lot about how the Boxer comics subvert this idea, by removing Mao from the equation.

And in a way, again, I think it has something to do with the spiritual or religious iconography of the Boxers. This sense that they are ‘old magic,’ older than Mao and the Party.

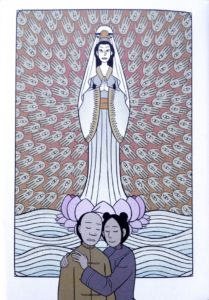

Going back to Yang’s graphic novels, is that the Boxer’s are only one side of the story, with the missionaries—‘Saints’—forming the other side. So there’s all of this great mirroring that goes on, where one character sees the Guanyin Bodhisattva at a critical moment, and another character sees Jesus.

Bao and Mei-wen dream of the Guanyin Bodhisattva while Jesus speaks to Vibiana

And there’s this very conscious borrowing of the Joan of Arc story to talk about the missionaries and kind of put them on the same level as the Boxers. I think for Yang, who is not only Chinese-American, but also Christian, this was maybe a necessary step to bring non-Christian readers to the table.

The covers to Gene Luen Yang’s two-part graphic novel, Boxers & Saints, placed side by side to form a single image

The covers to Gene Luen Yang’s two-part graphic novel, Boxers & Saints, placed side by side to form a single image

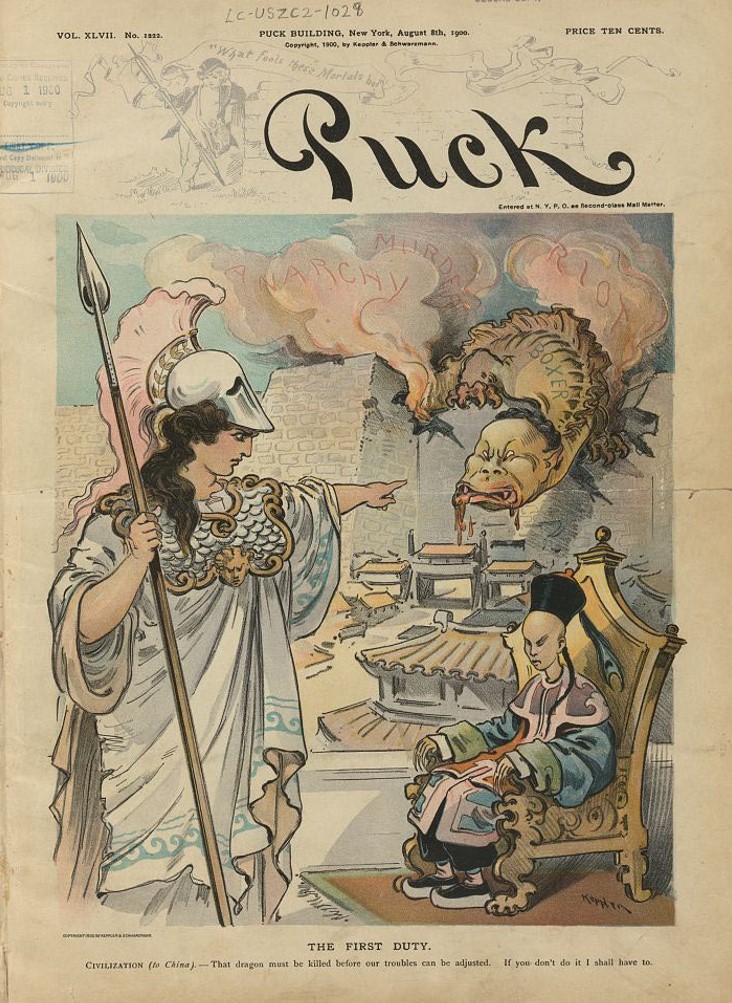

But actually, I think there was a sense that the missionaries really did see themselves as warriors for the faith. When I see contemporary cartoons like this one, from Puck:

…I don’t think this is nearly as a-historical as it might seem. If you can’t read this, the dragon here is called ‘Boxer’ and the caption reads:

CIVILIZATION (to China) – That dragon [‘Boxer‘] must be killed before our troubles can be adjusted. If you don’t do it I shall have to.”

So we don’t see the heroic side of the missionaries much in Zhang Shijie’s comics, and I think that’s the part that makes them really interesting. It’s not just timing, not just this sense that these stories basically became legends for an anti-imperialist Chinese nationalism rooted in Boxer uprising at the turn of the century, but that this was a conscious effort on the part of Zhang Shijie, who edited the stories to fit into the narrative he was trying to tell—much in the same way that Gene Yang edited his story about the missionaries to create something from whole cloth that was a little more relatable than spreading the gospel.

So how do we know he edited the stories? Well, actually it’s thanks to this guy:

This isn’t Zhang Shijie, this is Miao Yushi, an academic from Hebei who isn’t that much younger than Zhang Shijie actually (he was born in 39, Zhang was born in 31.) But Miao grew up reading Zhang’s Boxer Legends and—fortunately for us—wrote a blog post about them.

This is one of the challenges of studying someone like Zhang Shijie by the way—his stories, and the comics that were based on them, are easy enough to find, but the guy himself has mostly been forgotten.

So anways, Miao Yushi records that in the case of Fisher Boy, Zhang added three details to the original story he collected:

The description of the fisherman finding the magic fishbowl was embellished. An eight-line song was composed for Fisher Boy to sing while Fishing. The part where the fisherman talks back to county head and the missionary, and other details of their conversation.

试以他那篇著名的《渔童》为例,他在公布原始材料的同时,曾说他的加工有三处:一是渔翁得宝一段做了详细描写;二是把渔童的边钓边唱,具体化为八句歌谣;三是结尾处增加了渔翁问得县官和洋牧师哑口无言的情节和对话。

And he quotes, but doesn’t name Wang Zengqi (a student of Shen Congwen), who wrote in a 1958 essay published just before he was sent to labor reform as a rightist:

It would be hard to take the claim that this story appeared [exactly as Zhang wrote it down] some sixty years ago. The structure 形式 is so straight and to the point, and in language it is comparable to any number of much older stories (for example “[Three] Brothers Split Their Inheritance,” or “Little Red Riding Hood”). This particularly true of the song which Fisher Boy sings: The fishbowl goes shake shake shake, and the water goes splash splash splash!

我们几乎不大能相信这是一个仅仅产生在六十年前的故事。它的形式是那样的洗炼,它的语言可以跟许多流传最为久远的故事〈比如兄弟分家或狼外婆故事)相媲美。特别是渔童唱的那四节短歌: “鱼盆鱼盆摇摇,清水清水飘飘!

Now, if you have time, you can listen to the whole song from the animated version of the story, which was one of 16 short animated films released by the Shanghai Animation studio in 1959. One of the ways they cut costs that was really innovative at the time was by using paper cut animation, similar to stop motion with clay, but with an obviously more 2D effect:

In 1959 Fisher Boy 渔童 was made into an award-winning animated film by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, directed by Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴

In 1959 Fisher Boy 渔童 was made into an award-winning animated film by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, directed by Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴

We can see from both Miao and Wang’s appraisals of the story that it doesn’t really bother them that Zhang embellished his stories—Miao even argues that because the embellishments were so skilled, they actually form a sort of improvement on the original.

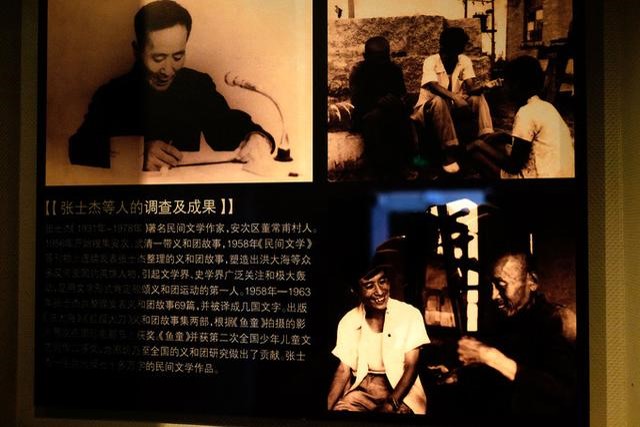

Okay so here’s a picture of Zhang Shijie, finally:

To try and understand him better, I’ve been doing my best to dig up his background info. Despite the enduring popularity of his stories, it hasn’t been a very easy process, with most the most useful sources being local histories collected by people like Miao Yushi.

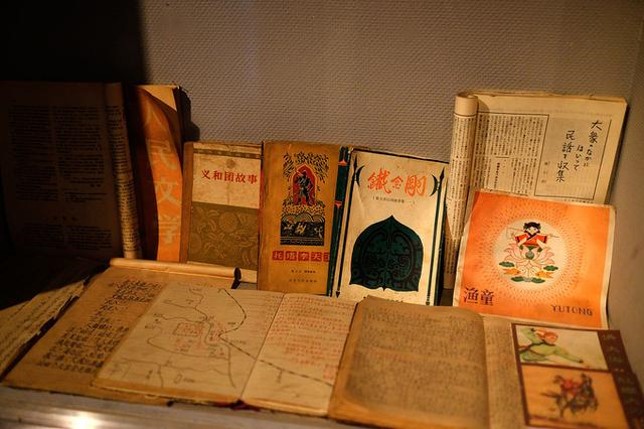

Between December 1957 and 1963, Zhang is known to have compiled and published at least 140 folk stories. Here are a few of his collections, and notebooks, from a display at the Zhang Shijie Museum in Langfang. (Check out the Boxer comics in the lower right-hand corner!)

Between December 1957 and 1963, Zhang is known to have compiled and published at least 140 folk stories. Here are a few of his collections, and notebooks, from a display at the Zhang Shijie Museum in Langfang. (Check out the Boxer comics in the lower right-hand corner!)

The info on his family background is sparse, but it appears he came from a poor peasant family. He did well enough in school to get sent to the Anci County Basic Teachers’ School (today Langfang Teacher’s University) and after two years there he was sent into the countryside to teach elementary school.

He moved around a lot and there is some suggestion that his health wasn’t very good, which pushed his interest in becoming a folklorist rather than a teacher. But he was apparently self-taught, and started collecting stories from older villagers (many of who had personally experienced the Boxer Uprising, which was focused in Hebei and northern China) in 1953.

His first stories came out in newspapers in 1956, and a collection appeared in 1957. In 1958 he became a full time writer, joining the Hebei state writer’s association. In 1960 he joined the national writers’ association, which still includes him on their website (which where I found the picture of him).

Altogether, Zhang is believed to have compiled and rewritten some 140 folk stories between 1957 and 1963, when he was targeted by the Socialist Education Movement.

But before all that happened, at the apex of his career in 1960 he was invited to the Third Congress of Literature and Arts Workers Representatives 第三次文代会, held in Beijing July 22 to August 13, 1960 and was hosted by Guo Moruo 郭沫若 with Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai welcoming the 2,300 representatives

The Third Congress of Literature and Arts Workers Representatives 第三次文代会, held in Beijing July 22 to August 13, 1960

The Third Congress of Literature and Arts Workers Representatives 第三次文代会, held in Beijing July 22 to August 13, 1960

In the local histories, of course, this pilgrimage is the real high point of the story:

Zhou Enlai especially set aside time to meet with Zhang Shijie in front of the Jade Garden Hotel. [When they met,] Zhang Shijie shook the Premier’s hand, tears streaming down his face. He said, “ I’m Zhang Shijie, from Anci, Hebei.” Premier Zhou smiled and nodded, saying, “You write the Boxer stories. You’ve really made a contribution [to our nation]. Keep up the hard work!”

周恩来总理特意抽出时间在翠明楼[翠明庄?] 接见了张士杰。张士杰紧握周总理的手,眼含热泪说:“我叫张士杰,河北安次人。”周总理微笑点点头“啊,你是写义和团故事的,你的贡献很大,以后要继续努力啊! ”

–from “The History of Langfang, Volume One: Famous Cultural Figures” 廊坊历史文化丛书文化名人卷3

Left to right: Guo Moruo 郭沫若, Mao Zedong 毛澤東, Zhou Enlai 周恩來, Zhou Yang 周揚, Mao Dun 矛盾

Left to right: Guo Moruo 郭沫若, Mao Zedong 毛澤東, Zhou Enlai 周恩來, Zhou Yang 周揚, Mao Dun 矛盾

Things seem to have gone well enough for Zhang to have a second story adapted into a short animated film…

Ginseng Baby 人参娃娃 (Dir. Wan Guchan 萬古蟾, Shanghai Animation Studio, 1962)

Ginseng Baby 人参娃娃 (Dir. Wan Guchan 萬古蟾, Shanghai Animation Studio, 1962)

But by the time he died in 1978 he was penniless and (apparently) trying to restart his career when he suffered a heart attack at his desk.

So how has he been remembered? Well, more recently, the author Feng Jicai, also from Hebei wrote a short essay praising his work, and both series of his comics have been reprinted. But really, like so many from his generation who were active in art and culture circles after 1949 and before 1966, Zhang himself is basically a forgotten figure. His legacy has been subsumed under the rubric of red propaganda.

Another shot of the Zhang Shijie Museum, with photographs from his later years.

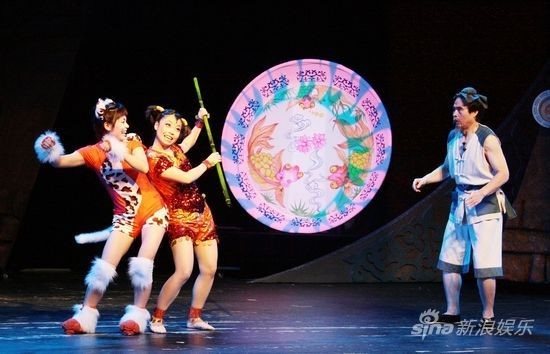

But I like to think that he’s more than that. Certainly, his legacy (if not his name) is lives on in PRC pop culture, everything from apps:

To stage adaptations:

For my purposes, I like to think of Zhang Shijie as another example of the creative response to political developments in China–much like the Shanghai Manhua Society of the late 1920s and early 1930s, or Ye Yonglie in the 1960s and again in the late 70s and early 80s. While it is easy to paint Chinese culture in broad strokes by looking at the big picture and big names, I’m increasingly convinced that the really interesting figures in any culture are the obscure and mostly forgotten writers and artists who made original work. Because, in the end, whether or not their creators are remembered, I would like to think that work that is truly original endures in a way that work which is simply derivative does not.

The Dude, as they say, abides.

- A Collection of the Best Shanghai Calendar Pictures from the Past Ten Years: 1949-1959《十年來上海年畫選集 1949-1959》 [↩]

- Said to be Tang, but definitely post-Yuan, and likely painted in the Ming. See Xia Ah’s comment on his Imperial Chinese Avengers. [↩]

- Langfang Cadre Theory Education Net 廊坊干部理论教育网, September 22, 2014 [↩]