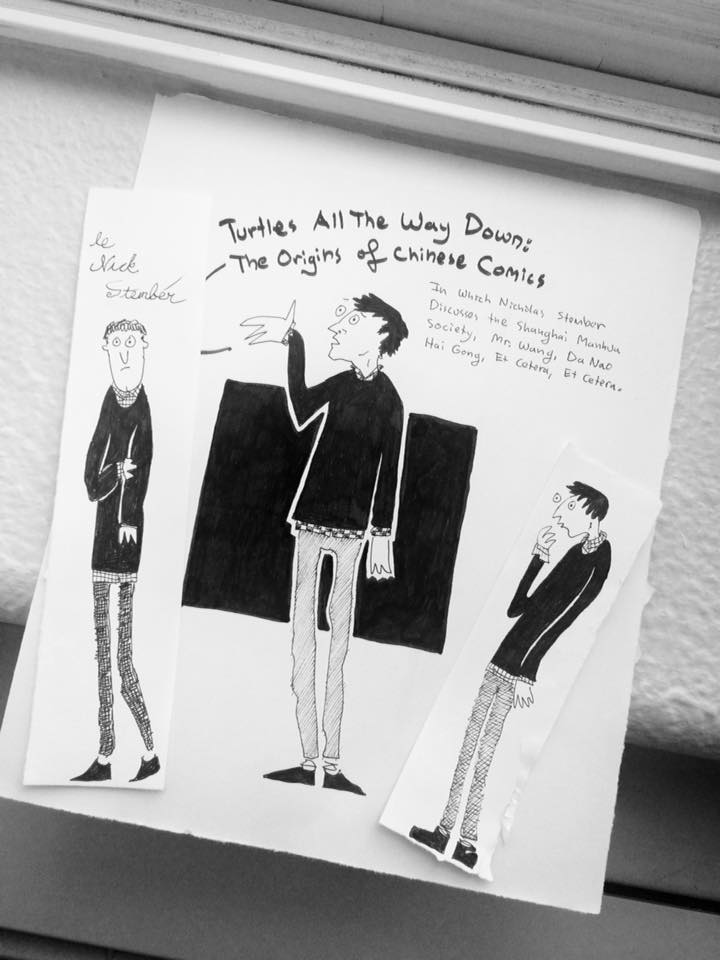

The following is based on a lecture on Chinese comics which I had the pleasure of presenting to the Asian Art and Visual Culture working group at the Townsend Center for Humanities at UC Berkeley on February 3, 2017, at the invitation of Hannibal Taubes and Weihong Bao. I’ve edited the original text slightly to reflect the comments I received before and after my presentation.

So, starting off, I’d like first thank the Asian Art and Visual Culture working group, and Hannibal Taubes and Professor Weihong Bao for inviting me to be here today, and Andrew Jones for taking the time to meet with me before this talk. It’s really an honor for me to be able to be here to not only share my research, but also have the opportunity to learn more about the projects you guys are all working on in your own fields. It’s always amazing to me to see the ways people studying things I had no idea about can inspire me to think about my own work in different ways.

I’d also like to take a moment to acknowledge the Chochenyo band (today Muwekma) of the Ohlone People on whose ancestral and unceded territory we are holding this event today.

Just now, Professor Jones and I were talking about this, and I said, “I know it seems a little hokey…” But Professor Jones, to his credit, said that he didn’t think it was hokey at all. And then he told me a story, one that I hadn’t heard before.

Just to preface, I’m from Portland, so we were talking about Ursula K. Le Guin, who has lived in Portland for most of her adult life with her husband, Charles Le Guin, a historian who taught at Portland State University (my alma mater).

What I didn’t know about Ursula K. Le Guin, is that she was originally from Berkeley, and her father, Alfred Kroeber, taught at the university. (That’s where the K in her name comes from.) Kroeber was an anthropologist, one the earliest students of Franz Boas at Columbia, and Le Guin’s mother, Theodora Kroeber, was also an anthropologist, having written Ishi in Two Worlds: a biography of the last wild Indian in North America in 1961. Ishi was said to be the last surviving member of the Yahi tribe, of the Yana people from Northern California, and he just appeared all of a sudden in 1911, after most of his tribe had been killed in the Three Knolls Massacre of 1865. The part of this story that I think is really relevant to my talk today, is that in her book, Theodora Kroeber describes how Ishi never actually told anyone his true name–just like Ged and the wizards in a Tale of Earthsea.

So we have these threads, the power of names, and the way ideas and traditions move through generations.

I’m going to try and avoid talking about politics here, because I know—or at least I think if you’re here for this talk today, it’s probably at least in part because you want to think about something else for a little while. But avoiding politics is itself political, and we are at Berkeley, which is in the national news for the protests here just two nights ago, for protests which ended in the university cancelling a talk by the white supremacist / internet troll Milo Yiannopoulos.

I would like to say that even though things look pretty dire right now, the struggle for equality and freedom from oppression is something that’s been ongoing for a long time now. I’d like to think that his Orangeness in Chief, and Brexit, and the crackdown on NGOs and lawyers and free speech in China…I’d like to think all of those things are just temporary setbacks.

I do think the tide of history is against them, in the same way that the First Nations peoples of North America, and indigenous peoples around the world are finally starting to gain some recognition for the injustices that were done to them in the past, and new policies are being put into place to address the ongoing legacies of those injustices.

And I want to thank the community here at Berkeley for standing up to the people who would have us the go the other direction, by having us betray the fundamental values of American democracy.

Okay! So, now, on the really pressing matter of the day: Chinese comics!

Statue of three stacked turtles in a public square in front of a curios shop.

Statue of three stacked turtles in a public square in front of a curios shop.

So, the title of this talk is ‘Turtles All the Way Down’ and I guess that’s a little confusing for some people, because what do turtles have to do with China or comics?

‘Turtles All the Way Down’ comes from a story that, I believe, Bertrand Russel liked to tell about an argument he had with a woman who didn’t believe that the Earth was round and orbited the sun. She thought—like many first First Nations groups actually held in their mythology—that Earth was supported on the back of a giant turtle. And so of course the question was, what supports the turtle?

So—stop me if you can guess the punchline—but the punchline was ‘Oh it’s another turtle, dear. Turtles all the way down!’

So it’s kind of cute way to talk about what philosophers call infinite regress. And I think it really applies to the question of ‘firsts’ in Chinese comics not just because it’s this great visual analogy, but there’s also some connections to Chinese mythology and art too!

Rosewood carving of three stacked turtles.

So we here we have a carving of that same statue, which is called 三叠龟 or ‘three stacked turtles.’ It’s not a very common image in Chinese art, but it goes back to (supposedly) this mountain in Jiangxi, which is a province way in the south of China, just over the mountains from Fujian on the coast:

Three-Turtle Peak 三叠龟峰 on Dragon Tiger Mountain in Jiangxi, children of Madame Turtle 龟娘娘 of the Dragon Palace of the East Sea 东海龙宫.

Three-Turtle Peak 三叠龟峰 on Dragon Tiger Mountain in Jiangxi, children of Madame Turtle 龟娘娘 of the Dragon Palace of the East Sea 东海龙宫.

The mountain is called, believe it or not, Three Stacked Turtle Peak, on Dragon Tiger Mountain. Now, for anyone who’s ever visited China, especially a Chinese mountain, you’ll probably already know that pretty much every single rock over a certain size has a name and is supposed to look like something. Or in a way, you could say it’s supposed to be something.

So this rock is supposed to be three sons of Madame Turtle, 龟娘娘, an immortal who served the Dragon King in the Dragon Palace under the East China Sea. (Dragons in China are traditionally aquatic, in case you’re wondering.) They even have names and personalities, like this one is the fat turtle and so on so forth.

But what’s really cool about this is that in most cases stories like this can be traced way back to the Sinicization of the various regions of China, which is especially true of mountains, which tend to be holdouts for what the PRC today calls ‘ethnic minorities’—but they used to call barbarians. So the analogy here becomes ‘the things which remain.’ The people are gone but the mountain, and the turtles, are still there.

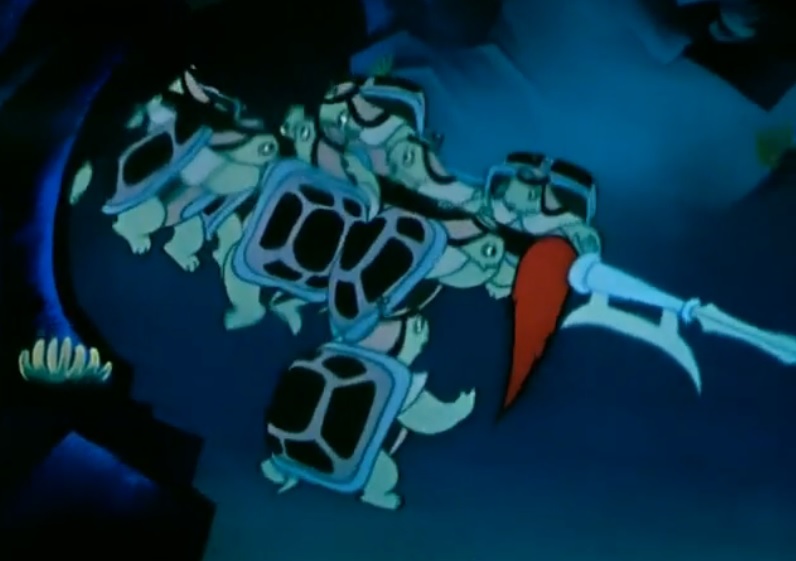

Film still from Havoc in Heaven 大闹天宫 (Wan Laiming, 1961,1964)

Film still from Havoc in Heaven 大闹天宫 (Wan Laiming, 1961,1964)

This is just an aside, if we have time, but this is a clip from the 1961 Chinese animated classic Havoc in Heaven 大鬧天宮, directed by Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴 (1900-1997), who belongs to the old guard of Chinese cartoonists we’re going to be talking about today. More turtles, although they don’t seem to have put in Madame Turtle, the mom so there’s that. Also, it probably bears pointing out that the Monkey King was born from a stone egg, and got trapped in stone under a mountain, so there are some connections there, too.

Things turning into stones, and stones turning into things.

Now, when we talk about Chinese comics—well, okay the second part of the title of my talk today is ‘Dr. Fix-it and Mr. Wang.’ And that’s pretty obscure, too, I’ll admit. Even the classic Chinese comics aren’t well known today. I had interview with CCTV yesterday, because they were doing a segment on comics in China. And, not surprisingly, the questions they gave me to prep were all about Japanese manga and anime. You know, ‘Why are they so popular?’ Because really, when you say ‘comics’ or manhua 漫畫 in Chinese today, people think you’re talking about manga, pretty much. Dongman 動漫, or ‘animation and comics,’ is almost exclusively so, even more than manhua.

But actually China has this amazingly rich tradition of comic books and cartooning that goes back to the 19th century. The problem is that, like with our stone turtles, things get obscured by the past. They don’t go away, really, but they become harder to see, harder to find, harder to talk about.

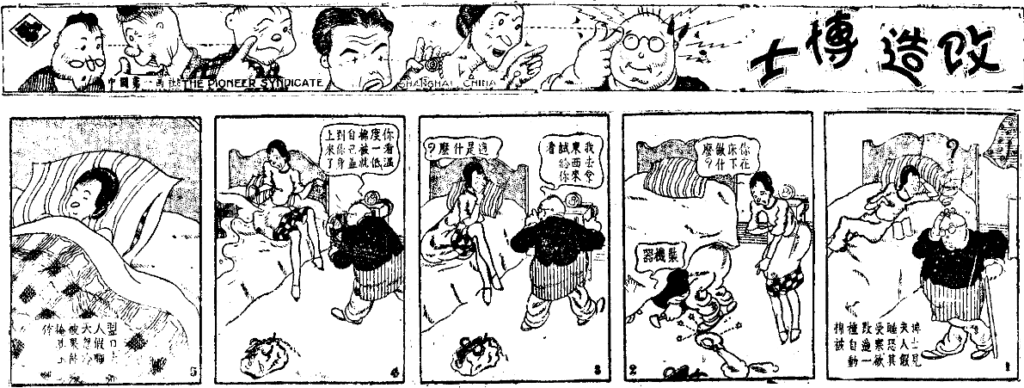

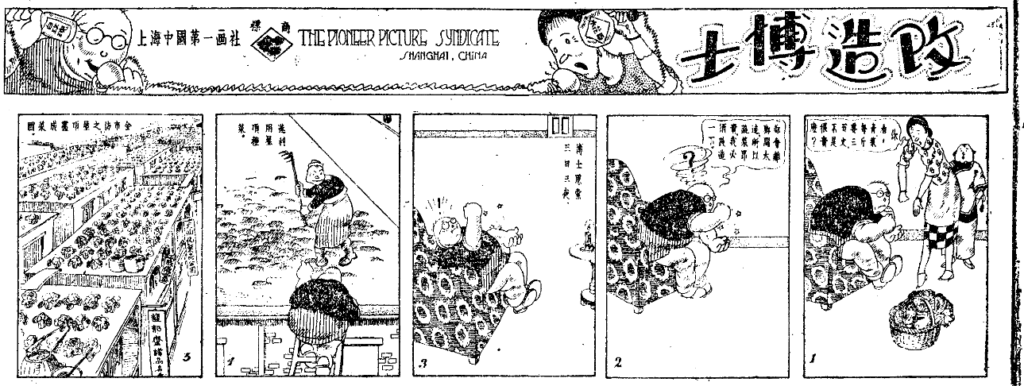

So this is Dr. Fix-it 改造博士, which, as far as I can tell is one of the earliest, if not the first, serialized comic strips in Chinese, appearing in the Shenbao 申報 on January 1st, 1928:

It was drawn by Lu Shaofei 鲁少飛 (1903-1995), who again, like Wan Laiming, belongs to this early guard of cartoonists who emerged in the 1920s and 30s, mostly in Shanghai. The jokes were written by Xu Zhuodai 徐卓呆 (1881-1958), who is a pretty famous figure in his own right.

But sequential art has been around for a long time in China, right? So what makes this ‘first’ or even one of the firsts?

I was talking to Hannibal last night about this, and as you already know Hannibal studies sequential art from the Buddhist tradition and in murals, on buildings and the like. And the question is, since these kind of narratives have been around for a long time, aren’t they comics in a way?

So here’s an example of a paneled fresco from Yu county I believe in Hebei—Hannibal you’ll have to correct me if I’m wrong!1

Left wall of the Lord Guan 關公 Temple in Yu county, Hebei

This is part of Hannibal’s field research, where he’s been going out and trying to find examples of things mentioned by anthropologists like Willem A. Grootaers, who is the author of Rural Temples around Hsüan-Hua (South Chahar), Their Iconography and Their History. In this case, we are looking at a wall fresco with illustrations of key events in the life of Guan Yu, a famous general from the Three Kingdoms period of the late Han who became deified over the following centuries.

In some cases, the narrative progression is clear even without knowing the context:

“Taking Xiangyang by Stratagem” 用計取襄陽

“Immediately Beheading Xia Houcun” 立斬夏侯存

So I do think these are, in a way, comics, but the challenge is, with anything, ‘rectifying the names’ as we say in China, 正名. In a more general sense, I think ‘comics’ (in the Anglophone world at least) have come to be defined as ‘narrative or sequential art.’ You know, art that tells a story over a series of pictures.

And a lot of this is thanks to this guy, who some of you (if you’re a comics nerd) have probably already read:

Scott McCloud had this great argument, which took comics away from the prescriptivist way of looking at them as being narrowly defined as ‘superhero comics,’ or ‘newspaper comic strips,’ essentially, and argued that instead that it’s much more productive to think of comics as being sequential art. Which is of course a descriptivist way of looking at things. Because that opens you up to a much wider range of content and possibilities than if you try to narrowly define comics by talking about the most common or popular definitions of the term.

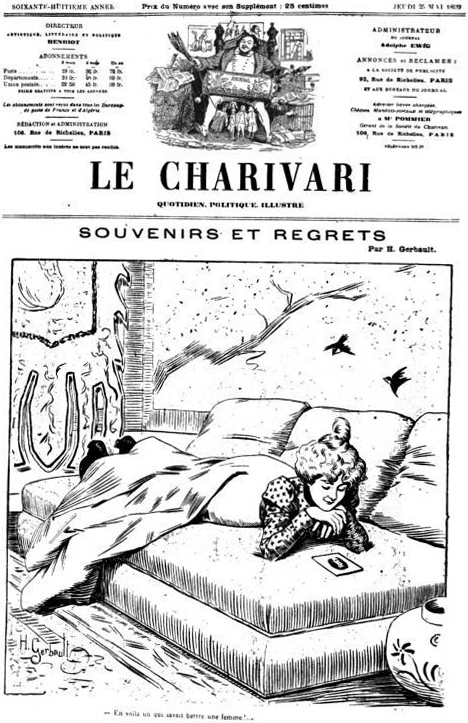

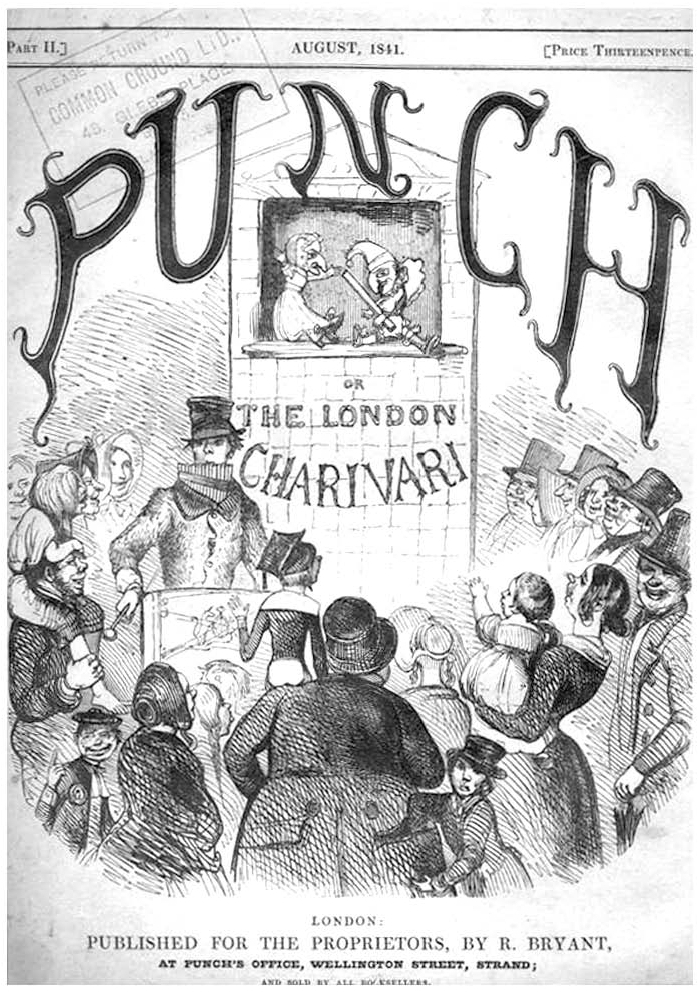

But personally, I think there was something that changed about sequential and illustrative art in the mid 19th century. This is when you have comics or cartoon publications like Le Charivari in Paris and Punch in London:

First Issue of Punch, or the London Charivari, August 1841.

First Issue of Punch, or the London Charivari, August 1841.

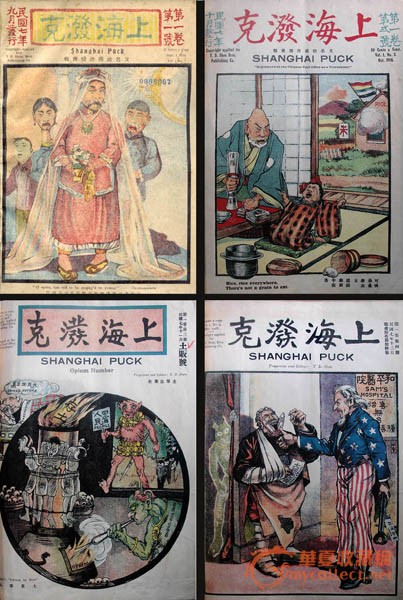

Publications inspired by the success of these comic periodicals appeared in places even as far flung as Hong Kong and Shanghai—Rudoph Wagner at Heidelberg has uncovered a lot of this, and my advisor, Chris Rea, at UBC has made some pretty compelling arguments for including these comics in the history of ‘Chinese’ comics, something that mainland academics have been somewhat loath to do.

The China Punch, May 1867, Hong Kong.

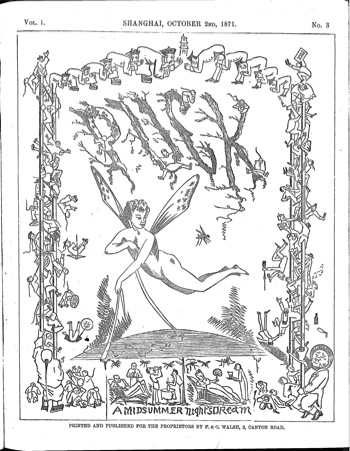

Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari, 1872.

Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari, 1872.

We should also mention ‘newspainting’ periodicals like the Illustrated London News, here which emerged around the same time and provided illustrations of recent events, along with the occasional cartoon or caricature.

So for my purposes, I tend to define the line between comics and the more general (and much earlier) sequential art as being one of technology that enabled artists to become more topical.

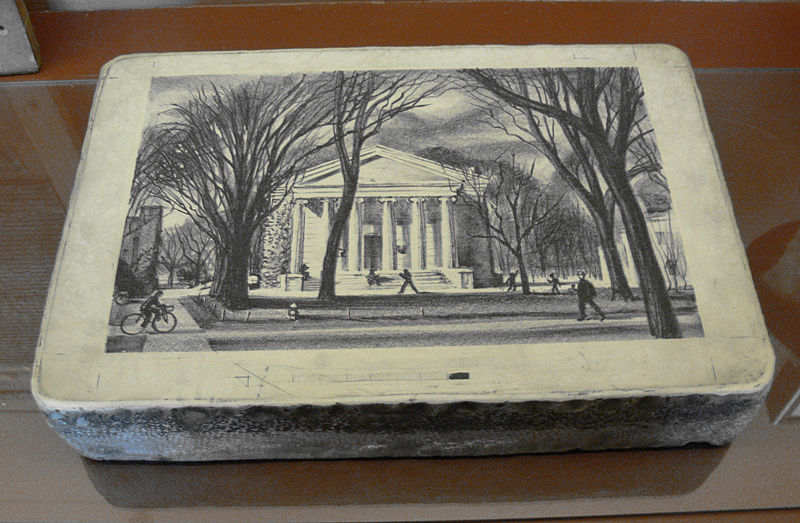

And the most important technological development that happened around the turn of the 18th century going into the 19th was lithography, invented by Alois Senefelder (1771-1834):

Above, we have a lithographic stone, which demonstrates the simplicity of Senefelder’s technique. Essentially, the artist draws a mirror image directly on the stone with a oil-based medium, over a layer of stone treated with acid or glue, usually gum arabic. This allows the negative space (the white areas) to attract water, while oil-based ink is attracted to the positive space (the black lines) and repelled from the water-saturated negative space.

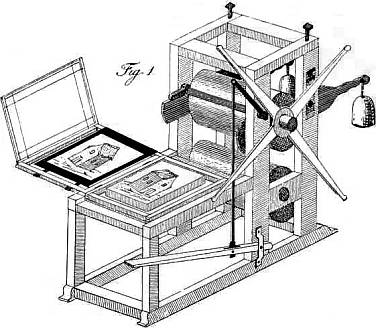

Eventually, lithograhic presses like the one below were developed to streamline the process:

Alois Senefelder’s original design for a lithographic press (From The Invention Of Lithography, 1818, translated into English in 1911)

Alois Senefelder’s original design for a lithographic press (From The Invention Of Lithography, 1818, translated into English in 1911)

The difference between lithography and earlier forms of printing was that it was cheaper and easier to do, and didn’t wear out like copperplate engravings did, so you could set it alongside type.

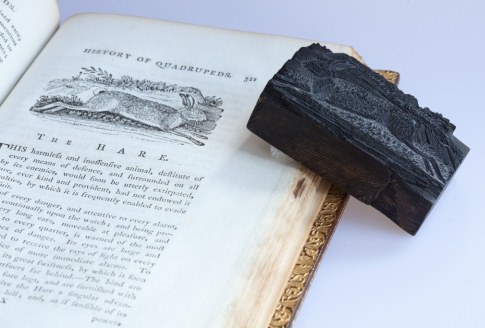

And there was actually a 2nd technological development that happened in the 18th century that doesn’t get talked about as much, which is boxwood engraving, as pioneered by Thomas Bewick.

This what was used for most of the book illustrations that are famous from this time period, like John Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice and Wonderland, mostly (I believe), because artists and printers could easily translate skills they had learned for engraving in copperplate to engraving in boxwood. Lithography required a different technique, since you were actually ‘painting’ or ‘drawing’ on the stone.

China has of course had a long history of woodblock printing that goes back at least to the Tang, and it was used right up to the turn of the 19th century, and even beyond in some cases, because of the challenge of setting movable type in Chinese characters.

The limitation I think with woodblock printing is that it favors formulaic, traditional art forms, because it takes so long to master. So by the time an apprentice is actually making his own woodcuts, he’s already pretty thoroughly indoctrinated into the traditional forms and stories.

You do start to see exceptions to this around the turn of the 19th century, with nianhua artists making topical prints on, for example, the Boxer Rebellion, but it’s still generally the exception to the rule. James Flath has written about this topic at length, both online and in print.

So, that brings us back to this questions of firsts in China, and what they actually did with the new printing technologies once they arrived. Here are some more strips for Dr. Fix-it:

Dr. Fix-It (Shenbao Sunday, February 1, 1928.)

Dr. Fix-It (Shenbao Sunday, December 1, 1928, 19.)

The ones that I’ve been able to decipher (unfortunately this is good as the quality gets when you’re working with the Shenbao newspaper digital archives) seem to be about a zany inventor who’s always coming up with useless inventions and driving his wife nuts with them.

So that’s probably pretty close to home for us as academics—the harebrained professor!

So as I mentioned, the first Dr. Fix-it strip appeared on January 1st, 1928. That date is important because….

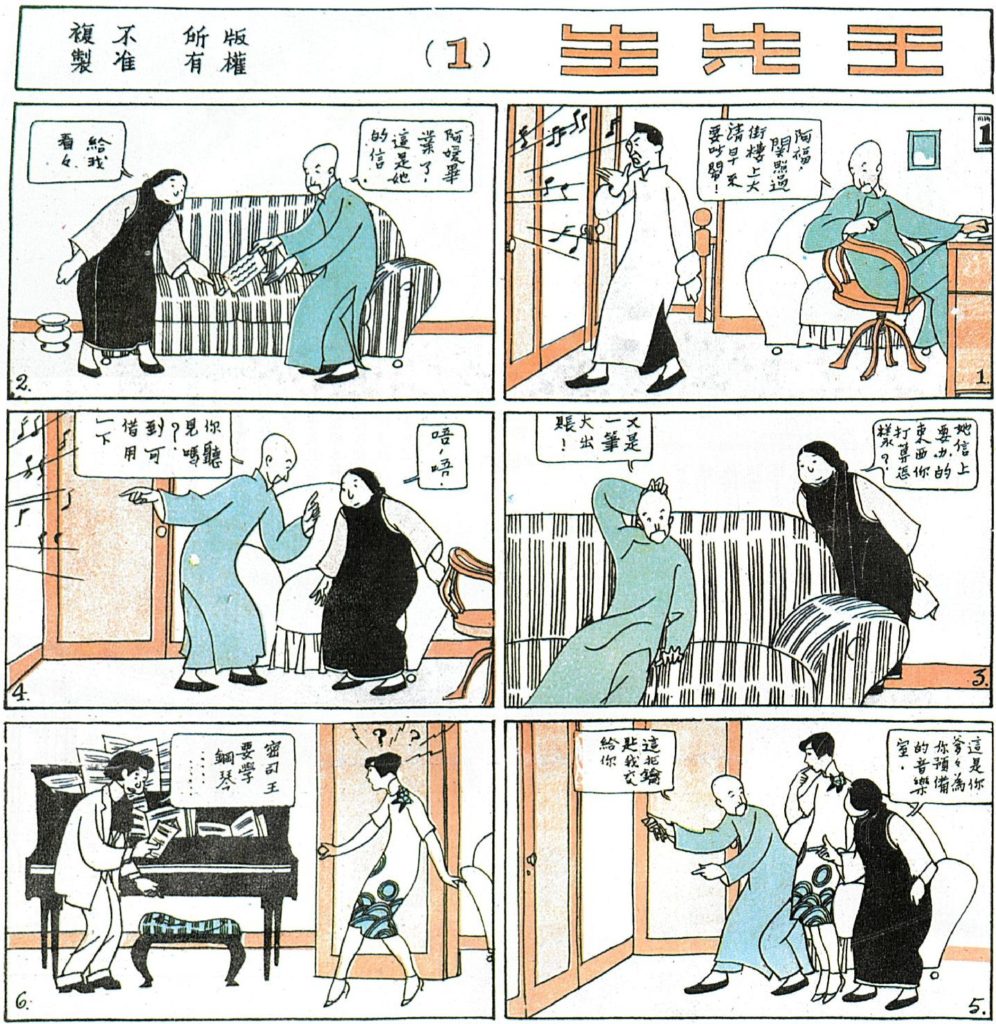

Okay, so here’s Mr. Wang, the other part of my title. Mr. Wang was created by Lu Shaofei’s best friend, or one of his best friends at the time, Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-1995), but it came out three months after Dr. Fix-it, and not in the Shenbao supplement, Casual Talk, but in a full color magazine called Shanghai Sketch.

Now, you’re probably thinking, ‘So what?’ Well, what’s interesting about this (to me at least) is that usually people who study Chinese comics (we exist! No kidding!) talk about Mr. Wang as being the first Chinese comic strip. And besides for that obviously not being true, it also seems to have obscured the history of Shanghai Sketch, which really was a groundbreaking publication, not so much for the content, but for the people it brought together and the way it set the stage for the ‘manhua boom’ of the early to mid-1930s.

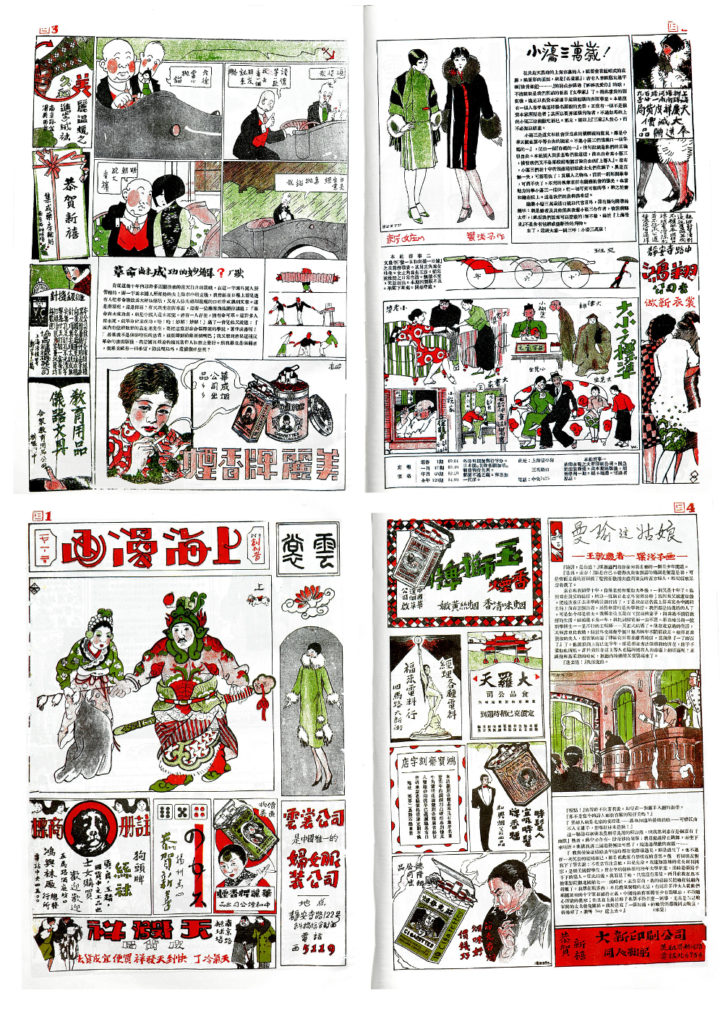

So Shanghai Sketch is often conflated with the Manhua Society, and in a way, that’s not wrong. There were actually several publications that came out with this name, the first being in January, 1928, and edited / written / and drawn by Ye Qianyu (the guy who created Mr. Wang), Huang Wennong 黃文農 (1903-1934), and Wang Dunqing 王敦慶 (1899-1990). You’ll also notice this is the same month that Dr. Fix-it came out. Unlike Dr. Fix-it though, which continued to some success over the next year and branched off into various spin-offs, the first Shanghai Sketch basically a flop that Ye Qian recalls having pulped in his autobiography from the 1980s.

It wasn’t even a magazine, really, it was a broadsheet that was meant to be folded, like a big pamphlet. Above is a picture of the cover…but really it looked like this:

Apparently Lu Shaofei and Ye Qianyu were neighbors at the time, and Ye had just been laid off from his job in the Northern Expedition, where he’d been hired by Huang Wennong. So Lu didn’t tell Ye about his new gig, and apparently Ye didn’t invite Lu to participate in his magazine, either.

That wouldn’t be all that unusual, if they didn’t know each other so well…

Since December 1926, in fact, Lu Shaofei and Ye Qianyu (and Huang Wennong and Wang Dunqing) had been founding members of the Manhua Society, along with Zhang Guangyu, his brother Zhang Zhenyu, Ding Song, Ji Xiaobo, and Hu Xuguang.

Here’s their emblem, designed by Hu Xuguang:

![Zhang Meisun “Emblem for the [Shanghai] Manhua Society” 漫畫會會徽 November, 1927.](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/manhua-society-emblem.png) Zhang Meisun “Emblem for the [Shanghai] Manhua Society” 漫畫會會徽 November, 1927.

Zhang Meisun “Emblem for the [Shanghai] Manhua Society” 漫畫會會徽 November, 1927.

And here is their first announcement, by Huang Wennong, in the Shenbao:

[Wang Dunqing, Ye Qianyu, and Zhang Zhengyu and I] drove out to Caojiadu, in the Western part of Shanghai, that colony of many square-miles in area north of the [Huangpu] River. The way they live there is really different from us Shanghai folk. We spent the better part of a day talking to them and after we got back home we elected Wang Dunqing to pick a topic to remember the day by, while I happily provided three casual illustrations, which we put up in the biggest Western-style restaurant in town. We also discussed some of the affairs of the ‘Manhua Society,’ It’s too bad our comrades weren’t there—Ding Song, [Zhang] Guangyu, [Hu] Xuguang, [Lu] Shaofei, [Ji] Xiaobo—otherwise I would have a great deal of interesting news to report to our readers.

我們…坐了汽車到滬西的曹家渡, 那處數方里的江北殖民地, 他們生活, 絕對不和上海人同化, 我們費了半天的光陰, 和他們交際, 回來公推王敦慶選一篇記事, 我很高興, 隨意繪了三方插畫, 並且在鎮上一家規模最宏大的番菜館裏, 議論一些「漫畫會」的事情, 可惜尚有五位同志— 丁松, 光宇, 旭光, 少飛, 小波. —沒有同去. 否則還有許多有趣味消息報告讀者呢.

– Huang Wennong, Shenbao on December 1, 1926

Here’s the second, more formal, announcement:

MANHUA SOCIETY FOUNDED

A number of artists with rich imaginations from Shanghai have formed a drawing club, for which they have chosen the name the “Manhua Society.” Regarding the nature of the club, it differs greatly from other drawing clubs. In the next few days a manifesto will be published. The members are (by stroke count in the character of the family name): Ding Song, Wang Dunqing, Hu Xuguang, Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhenyu, Huang Wennong, Ye Qianyu, [and] Lu Shaofei. The club address is Zhejiang Rd, Ningbo Rd, No. 65, Floor 3, No. 40.

漫畫會之成立

上海現有數位思想豐富之畫家組織一畫會、定名漫畫會、按漫畫會之性質、與其他畫會逈異、不日將有宣言發表、發起人以姓氏筆劃為次、丁悚·王敦慶·胡旭光·張光宇·張振宇·黃文農·葉淺予·魯少飛·會址浙江路寗波路六十五號三層樓第四十號

– Shenbao on December 7, 1926

Finally, these announcements were followed by a rather stirring, if obtuse, manifesto:

MANHUA SOCIETY PUBLISHES MANIFESTO

On Saturday, in Shanghai, the Manhua Society convened an ad hoc meeting at their headquarters. On this day they discussed and passed the following resolutions, one by one: [1] within the year, this society should organize a formal founding meeting, and we recommend that Ding Song and Zhang Guangyu handle this matter [2] the manifesto drafted by Huang Wennong and Wang Dunqing has also already been approved by the entire body of the society, and is included herein:

Recently, drawing clubs have been established like flower buds in the spring, like the surging tides in autumn. Does this mean that the future of art is bright? Or is it a case of making use of unity to cultivate a grand reputation for a given group? Nobody can say for sure, but in the case of our little group at least, we’ve come together purely out of mutual interests and ambitions. Each and every one of us must find a balance between our innate abilities, intelligence and experience. In our artwork, we must express our romanticism, for the sake of advancing the human mind. In other words, we want to make this human society of ours into new soil for the tiller. Whether or not the products of our hearts and blood will able to be thought of as a labor of art, and whether or not it will measure up to our ideal goal is not a question that can be answered objectively. Although it is something which cannot be measured at present, it is our hope—and our pledge—is to work together to plant good seeds in this time of artistic immaturity. In the future, when it comes time to reap the fruits of our labors, probably not a single member of our group will be willing to go forth and enjoy them.

漫畫會發表宣言

上星期六日、漫畫會在會所內召集臨時會議、是日將章程逐條討論、並均通過、又該會准於本年內、開正式成立大會、推定丁悚·張光宇·辦理其事、黃文農、王敦慶·擬稿之宣言、亦經到會全體之認可、茲特錄載於次、近來畫會的創設、好像春之花蓓蕾着、秋之潮澎湃着、這是繪畫藝術界前途的光明嗎、或是要假團結力的作用來樹黨稱雄呢、誰也不能給我們一個透澈的定斷、可是我們幾個人的組合、完全因為是志趣相投、就是我們之中的各個份子、都要全平自己的天性、智力和經騐、在我們的藝術作品上表現、我們的浪漫主義、使人類的思想向上、換句話說、就是要使這個人類社會、成為我們所開拓的新土地、然而我們的心與血的結果、能不能够被認為藝術上的工作、和能不能够達到我們理想上的目的、那是一種客觀上的問題不可、旦不能在此時量到、不過我們的願望、——也是我們的誓語、——是要在這幼稚的繪畫藝術期間、同心努力、播下良好的種子、也許將來的收穫、我們沒有一個份子情願去享受的。

– Shenbao on December 21, 1926

So we have three friends (four if you count Ji Xiaobo) who spend much of 1927 together, working on the Northern Expedition, with Lu Shaofei in Nanjing, and Huang Wennong and Ye Qianyu first in Shanghai and then in Nanjing as well, making anti-imperialist posters and organizing fundraising events for the KMT. And then all of sudden, they lose their jobs. One of them gets a paying gig at a newspaper and doesn’t tell the others, and two of them go off and try to start a magazine without inviting their friends.

So what happened? Well, as you might expect, it’s hard to say for sure, since the only surviving accounts are a short interview with Lu Shaofei and Ye Qianyu’s autobiography, which is rather hazy on the dates during this time period. (He suggests that the Manhua Society was founded in late 1927, for example.) But the smoking gun appears to the Shanghai Massacre of April 12, 1927, which may have led to a coup within the group that had Ding Song replaced by the much younger and left-leaning Wang Dunqing.

REGULAR MEETING NOTES FOR THE MANHUA SOCIETY

The day before yesterday (the 6th), the Manhua Society held their fourteenth regular meeting at their club headquarters on Rue Admiral Bayle. Present at this meeting were Zhang Meisun, Ji Xiaobo, Lu Shaofei, Ding Song, Zhang Guangyu, Ye Qianyu, Wang Dunqing, Zhang Zhenyu, Huang Wennong. Aside from auxiliary member Cai Shudan being in Ningbo, and Hu Xuguang taking an absence due to illness, all members arrived on time. First, chairperson Ding Song announced that he would be stepping down. After reporting the motions of the previous meeting, members began discussing various matters, regarding the development of the Manhua Society, with all members participating in a productive discussion. Zhang Meisun was encouraged to carve a club emblem and Wang Dunqing was appointed chairperson for the next meeting. Various members shared their latest work, of which there was relatively more than last time, and at around 5pm the meeting was concluded.

漫畫會常會紀

漫畫會前日(六號)於貝勒路三十號會所、開第十四次常會、到會者張眉孫·季小波·魯少飛·丁悚·張光宇·葉淺予·王敦慶·張振宇·黃文農、除外埠會員蔡輪丹在寗、胡旭光因病請假外、全體均准時到會、首由丁悚主席致開會辭、報告上屆議案後、開始商議各種問題、關於會務發展、咸有切實之討論、又推張眉孫彫刻會徽、王敦慶為下屆主席、各會員所交新作品、較上次更多、會議至五時始散。

– Shenbao on November 6, 1927

After the communists came to power in 1949, everyone who was in Shanghai during the late 1920s got very fuzzy about where they were in April, 1927, and the months which followed. In the case of the Manhua Society, it led to three members losing their jobs with the KMT–only Ji Xiaobo was able to stay in the party, as a (reputedly) undercover member of the KMT censorship apparatus in the education bureau.

So while Lu Shaofei was getting ready to launch Dr. Fix-it with Xu Zhuodai, Wang Dunqing, Ye Qianyu, and Huang Wennong were getting ready to launch Shanghai Sketch. After Shanghai Sketch folded after it’s first issue, Zhang Guangyu eventually organized and financed a relaunch, which appeared on April 21, 1928:

First issue of the relaunched Shanghai Sketch 上海漫畫, cover by Zhang Guangyu. April 21, 1928.

First issue of the relaunched Shanghai Sketch 上海漫畫, cover by Zhang Guangyu. April 21, 1928.

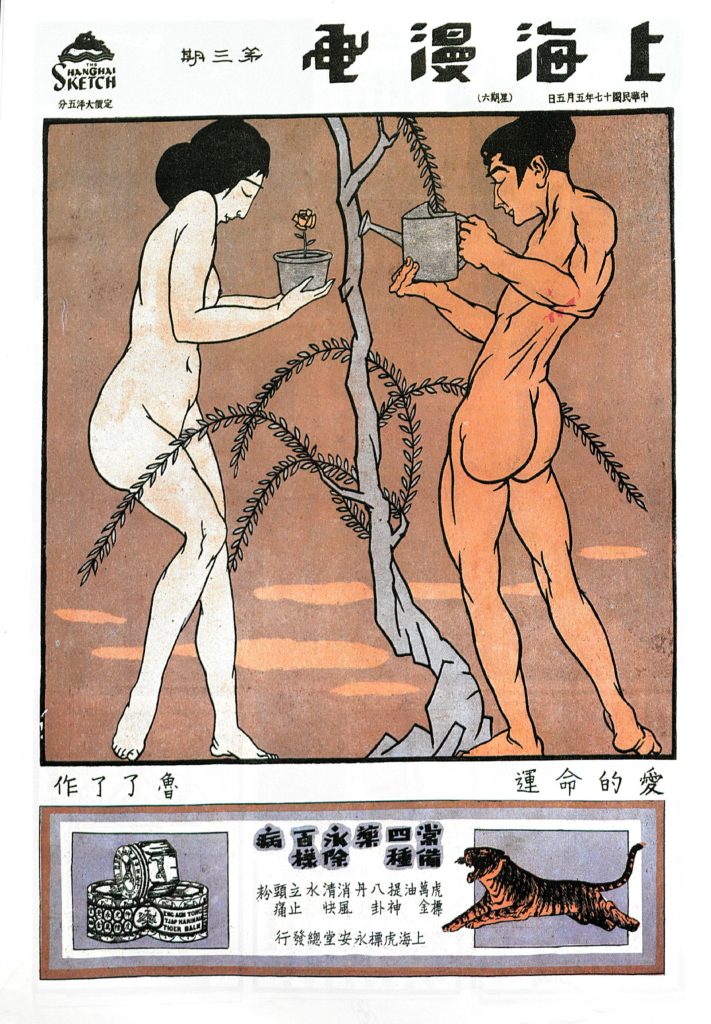

Although Ye Qianyu was hired as the editor of the relaunched Shanghai Sketch, which prominently featured cartoons by Huang Wennong, Wang Dunqing was nowhere to be seen, having fallen out with the group (according to Ye Qianyu’s autobiography) due to an unspecified disagreement with Zhang Zhenyu. Even Lu Shaofei eventually started drawing for Shanghai Sketch–albeit under a pseudonym, possibly to avoid a breach of contract with Xu Zhuodai and folks behind Dr. Fix-it. Here is the cover to the third issue of Shanghai Sketch, drawn by ‘Lu Liaoliao’ 魯了了:

So what really happened to the ever enigmatic Wang Dunqing?

Here we can see one of the few cartoons I’ve been able to track down by him. For a long time this image has floated around the internet and in other places without anyone connecting it back to him, because he used a pseudonym, Wang Yiliu 王一榴. When I was researching my MA thesis, I came across an article which mentioned some of his pseudonyms, and so I was able to track this down that way.

That’s how I found out he belonged to the League of Leftwing writers the 左联, an organization of writers who promoted socialist realism, and many of whom belonged to the Chinese Communist Party.

![Wang Yiliu [aka Wang Dunqing] “Founding of the League of Left-Wing Writers” 左联作家联盟成立 Shoots萌芽, Issue 4, April 1930, 7.](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/wang-yiliu-wang-dunqing-left-league.jpg) Wang Yiliu 王一榴 [aka Wang Dunqing] “Founding of the League of Left-Wing Writers” 左联作家联盟成立 Shoots萌芽, Issue 4, April 1930, 7.

Wang Yiliu 王一榴 [aka Wang Dunqing] “Founding of the League of Left-Wing Writers” 左联作家联盟成立 Shoots萌芽, Issue 4, April 1930, 7.

It’s not really surprising that Wang Dunqing would have wanted to hide his identity though, since was the best educated of the group, who were mostly the sons of small business owners, artisans, loggers. Ye Qianyu (1907-1995) also came from wealth, to a certain degree, since his father was a merchant who was able to send him to private schools. But he was much younger, and dropped out of school earlier than Wang Dunqing.

Actually, an interesting coincidence that I’ll get into more in a bit is the fact that at least three of the Manhua Society members were orphans, and the remaining two were mostly self-taught.

But Wang Dunqing attended the prestigious St. John’s University, where classes were taught in English. Like most young men of means back then (and also today), he was getting ready to study abroad when his father died, rather suddenly, leaving him to take care of his family.

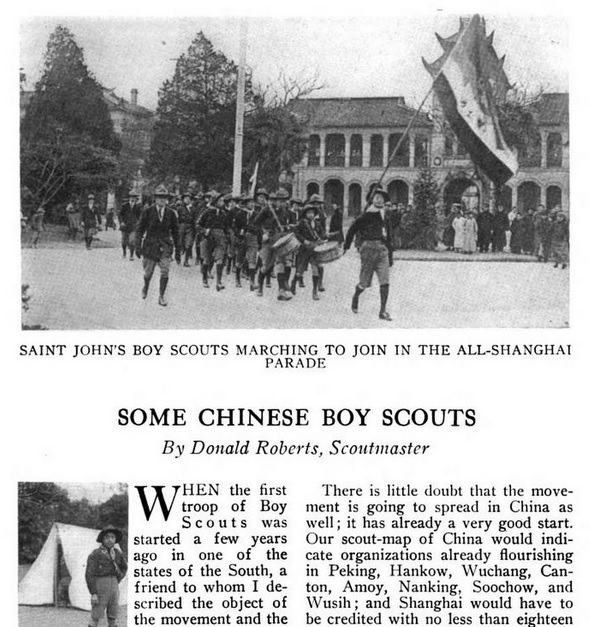

He made ends meet by working as a school teacher, but his real passion was for cartoons, something he seems to have picked up from Donald Roberts, a professor of English and History whose collection of Republican broadsheets is held by the Princeton East Asian Library:

The reason, incidentally, we know they knew each other is because Donald Roberts helped introduce the Boy Scouts to China, with Wang Dunqing being one of the founding members of Donald Robert’s troupe.

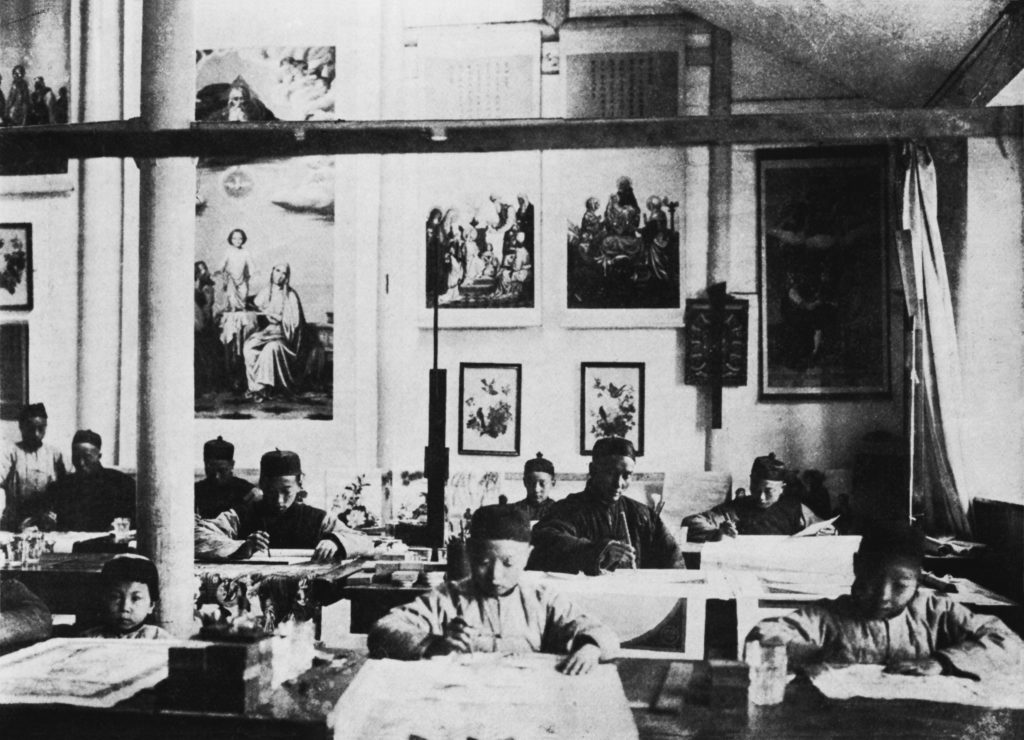

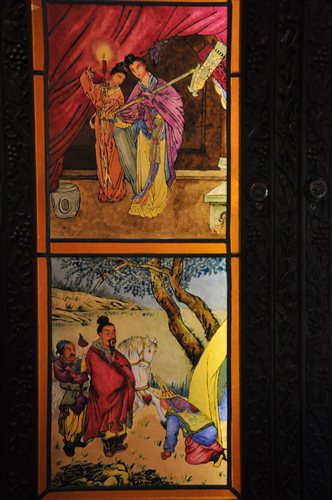

Ding Song, on the other hand, was basically the complete opposite of Wang Dunqing having been raised, along with his brother, by the Jesuits at an orphanage in Xujiahui, called Tushanwan.

It wasn’t just an orphanage though, it was a workhouse and a school that taught Chinese children how to draw and paint and carve, both to produce religious iconography….

…but also to make furniture and other items for export, like this stained glass cabinet:

Ding Song got his start in comics in the 1910s through another foundational figure, Shen Bochen (1889-1920) who published the first bilingual cartoon magazine in China, the Shanghai Puck in 1919.

And this brings us back to the question of firsts and the problem of prescriptivism. The word for comics in Chinese is manhua, of course, but before Feng Zikai’s work came to prominence under that name in 1926 though, comics in China were mostly known as ‘satirical pictures’ 諷刺畫, and that’s actually the other name for Shen Bochen’s magazine: Bochen’s Satri伯尘諷刺畫報.

Here is one of his more famous cartoons, published just after the October Revolution of 1918:

![“Your time has come!” [Russian Czar, German Kaiser] Shen Bochen in Shanghai Puck 上海泼克, 1918.](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/comic-in-china-YouTimeHasCome-1024x721.jpg) “Your time has come!” [Russian Czar, German Kaiser] Shen Bochen in Shanghai Puck 上海泼克, 1918.

“Your time has come!” [Russian Czar, German Kaiser] Shen Bochen in Shanghai Puck 上海泼克, 1918.

The thing that’s really interesting about Ding Song, though, is the way he embodies the transfer of printing skills and technology from West to East, via the missionaries.

Around the same time as lithographs are starting to come into vogue, you also have organizations like the London Missionary Society, who were training missionaries in foreign languages, like Chinese, and having them translate and publish the Bible in Chinese.

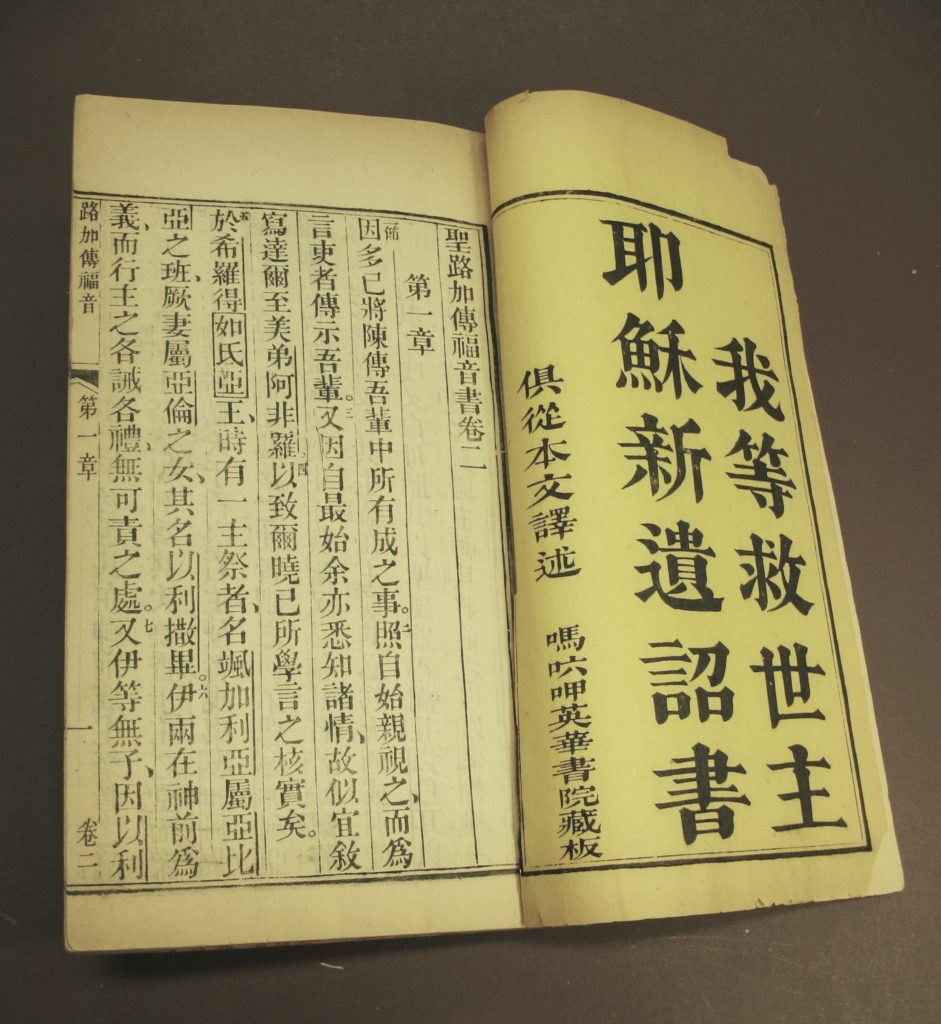

So here’s one the earliest translations of the New Testament into Chinese, which was printed around 1813 using woodblocks:

Translation of the New Testament by Robert Morrison (1782-1834), William Milne (1785-1822), and Liang Fa (1789–1855), woodblock printing 1813-15 (Old Testament was not completed until 1823), London Missionary Society.

Translation of the New Testament by Robert Morrison (1782-1834), William Milne (1785-1822), and Liang Fa (1789–1855), woodblock printing 1813-15 (Old Testament was not completed until 1823), London Missionary Society.

!["W[ALTER HENRY] MEDHURST (1796-1857) in conversation with Choo Tih Lang attended by a Malay Boy." China: Its State and Prospects (John Snow, London, 1838)](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/173_0004.jpg) “W[ALTER HENRY] MEDHURST (1796-1857) in conversation with Choo Tih Lang attended by a Malay Boy.” China: Its State and Prospects (John Snow, London, 1838)

“W[ALTER HENRY] MEDHURST (1796-1857) in conversation with Choo Tih Lang attended by a Malay Boy.” China: Its State and Prospects (John Snow, London, 1838)

Some of the key figures here are Robert Morrison (1782-1834), William Milne (1785-1822), and Liang Fa (1789–1855), and Walter Medhurst, who (1796-1857) who over time put out several successive translations as their mastery of the language improved, and they realized the importance of targeting regional dialects, and prestige dialects like classical Chinese.

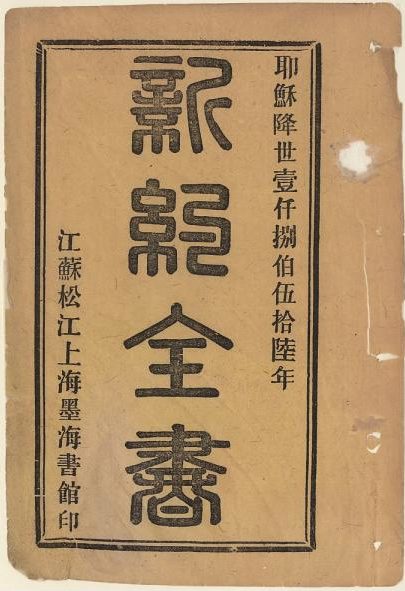

Medhurst is really important for us, though, because he lived in Shanghai, where he published his own translation of the Bible into classical Chinese in 1854, known as the Delegates Version:

1857 printing of Medhurst’s 1854 Delegates Version 委辦譯本 or 代表譯本 of the Bible.

1857 printing of Medhurst’s 1854 Delegates Version 委辦譯本 or 代表譯本 of the Bible.

Rather than use woodblocks though, Medhurst used lithography, which you can tell from the smooth (rather than angular) lines of the above image. His press, which was located near Shandong Road and Fuzhou Road by the Bund and Old Chinese city was called Maijiajuan 麥家圈. Mai means ‘Medhurst,’ after the first character in his Chinese name, 麥都思, jia means ‘family,’ and juan means ‘sty’ or ‘pen.’ Why pen?

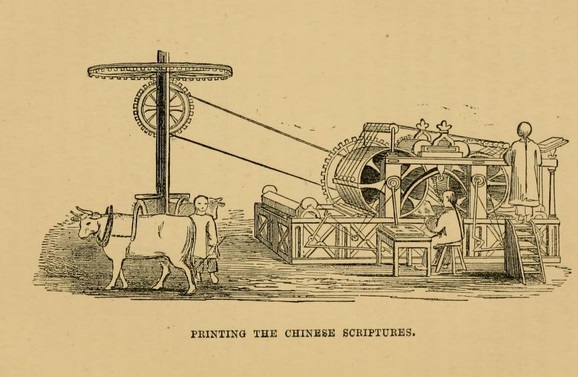

Early ox-driven missionary lithograph press. Model for Maijiajuan 麥家圈 [The Medhurst Family Pen]? Cecelia Lucy Brightwell – So great love : sketches of missionary life and labour by Cecelia Lucy Brightwell (John Snow and Co., London, 1873)

Early ox-driven missionary lithograph press. Model for Maijiajuan 麥家圈 [The Medhurst Family Pen]? Cecelia Lucy Brightwell – So great love : sketches of missionary life and labour by Cecelia Lucy Brightwell (John Snow and Co., London, 1873)

Well, it turns out that early lithographic presses in China were ox-powered, as in the illustration above. What’s really crazy though, is when Zhang Guangyu and Ye Qianyu decided to relaunch Shanghai Manhua in March, 1928, they ended up renting the a room in the old Medhurst press–even though Ye misrembers Maijiajuan as Maijiayuan 麥加園, it seems obvious that he was talking about the same place, since he describes it as being “the back room in an old church.”

So there is this history there, stacked like the turtle analogy we started the talk with.

And if we move forward, the German rotogravure press which ‘playboy’ investor Shao Xunmei imported to replace Shanghai Manhua’s out of date lithographic presses in 1934 were sold for a nominal sum to the communists in 1949 in a bid for clemency, in turn allowing the next generation of graphic artists to publish not only comics, but also the propaganda posters for which the PRC would become known for.2 So it’s not just turtles all the way down, but all the way up, too.

The thing that really motivates my research is that I don’t think that the legacy these guys left is being kept alive today, outside of academic circles. Which seems like something that would disappoint them, given their interest in making ‘popular’ media. So hopefully this talk, and my ongoing project online, at the Encyclopedia Manhuanica, will encourage more people to go out there and hunt through the archives and see what there is that hasn’t been dug up yet!

As a bonus, just after my talk I was handed the following drawings, which on top of being able to nerd out on Chinese comics for an hour and a half pretty much made my day:

- As it turned out, the image I pulled from Hannibal’s blog for my talk turned out to be of dubious narrative quality. At his suggestion, I’ve included images from a Guan Yu Temple instead. [↩]

- See Jonathan Hutt “Monstre Sacré: The Decadent World of Sinmay Zau 邵洵美” [↩]