Zhang Guangyu’s 張光宇 (1900-1965) overlooked masterpiece, Manhua Journey to the West 西遊漫記 was originally created in the fall of 1945 while Zhang was living in the wartime capital of Chongqing. Deeply critical of the ruling KMT government, it was eventually banned and did not see print for another 13 years. For the sake of introducing Zhang’s out-of-print work to a larger audience, I’ve taken the liberty of translating the entire 60 page comic into English and will be posting it in installments on my blog over the next several weeks.

In part 2 of this 6 part translation, Tripitaka and his three disciples, Monkey, Pigsy, and Sandy find themselves in the Kingdom of Paper Money, where advances in agricultural production have made it possible to grow money to replace gold and silver. 1 When the the rulers of the Kingdom of Paper Money, Emperor Xizong 熙宗皇帝2 and his wife, Empress Dai Ling 黛玲皇后 discover Zhu Bajie’s special ability, however, they quickly hatch a plan to make the most of this ‘golden opportunity.’ Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Ey-qin, 埃秦 the Pharaoh3 has dispatched his most trusted advisor, the Crested Falcon 毛尖鹰4 to build a Great Wall of Ten Thousand Li with the help of the cruel “Crow-crow Birds”…

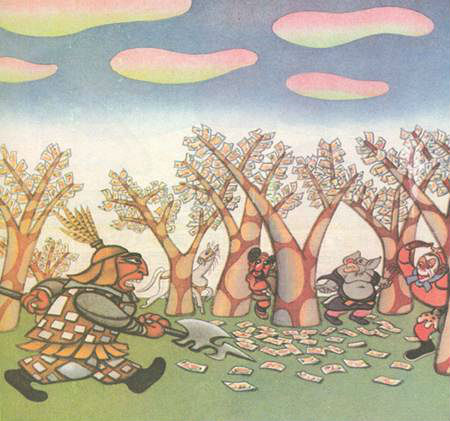

11. 正在闹轰轰,忽然远处气喘喘急步跑来一个人,手持武器喝声:“强盗!敢犯国法,你们休要偷我们的钞票!”大家急得连声说:“抱歉!抱歉!过路只不知底细,未曾问过明白,请教!请教”后来经这个人解释,原来这里是“纸币国”境界,他是看守纸币的围警,纸币可代金银使用,经国王数度改革,现在已由工业生产进至农业生产,全国遍种“纸币”可供大量使用,十分便利。

Just as they were making an uproar, suddenly a breathless person came running over, a weapon in his hands. He shouted, “Bandits! You dare violate the law of land! Don’t even think about stealing our money!” Everyone hurriedly shouted, “Sorry! Sorry! We were just passing by and didn’t know what was what, and didn’t have a chance to understand the situation, please instruct! Please instruct!” In the end, following this individual’s explanation, they learned that this was the border to the “Kingdom of Paper Money,” and that he was a paper money guard. Paper money could be used in the place of gold and silver, and following a number of reforms by the king it had advanced from industrial production to agricultural production. All over the country “paper money” was being grown to meet a massive demand, and all in all it really was rather convenient.

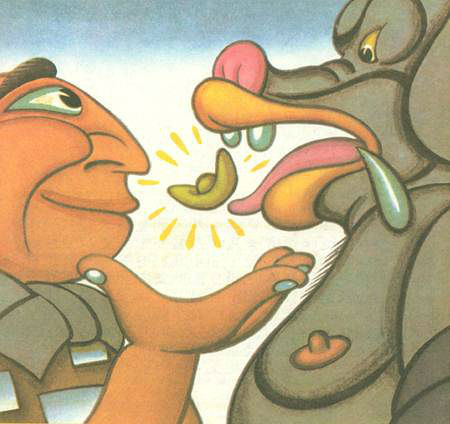

12. 这人又道:“入境的人,可留下金银,兑换“纸币”方准过去!”三藏等觉得这辨法很好,笔录下来,留作参考,至于被八戒摇下来的一堆“纸币”,由八戒肚子里吐出黄金一锭交与围警作为兑换金,就算和平了事。

The guard continued, saying, “Those entering our borders can leave gold or silver, which can be converted to ‘paper money’! Tripitaka and the others thought this was all rather fine, and so they wrote down the sum of the pile of money shaken down by Bajie. for reference. Bajie then spat out a gold ingot which had been hidden in his stomach to exchange for the paper money and with that everything was settled.

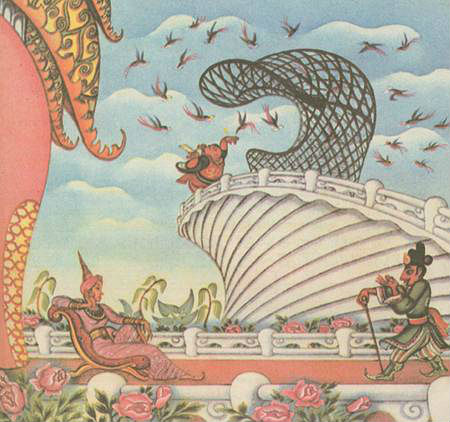

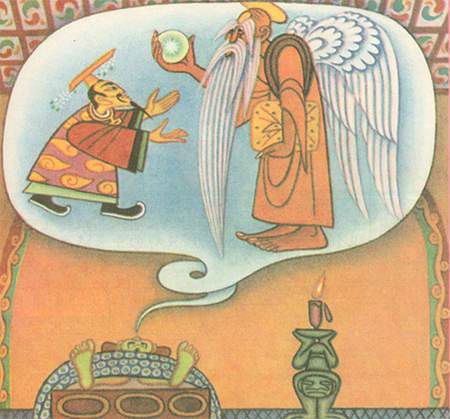

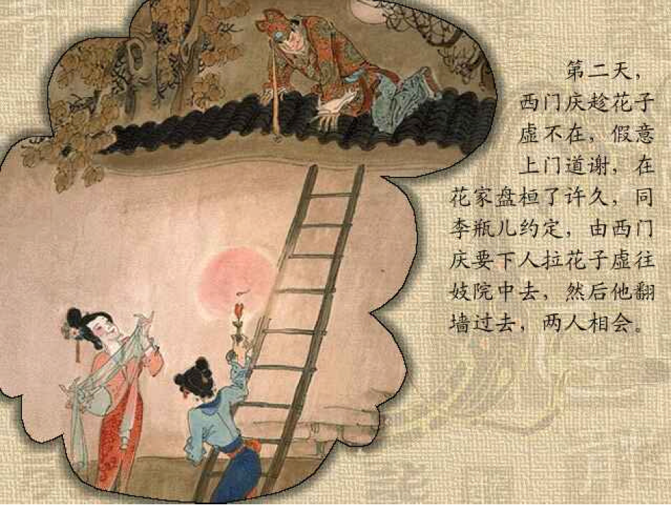

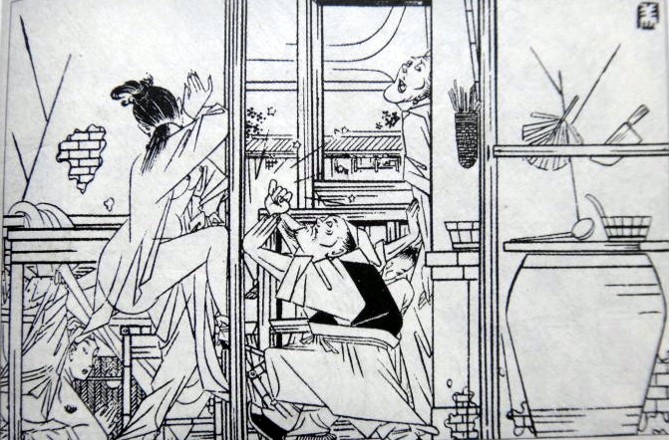

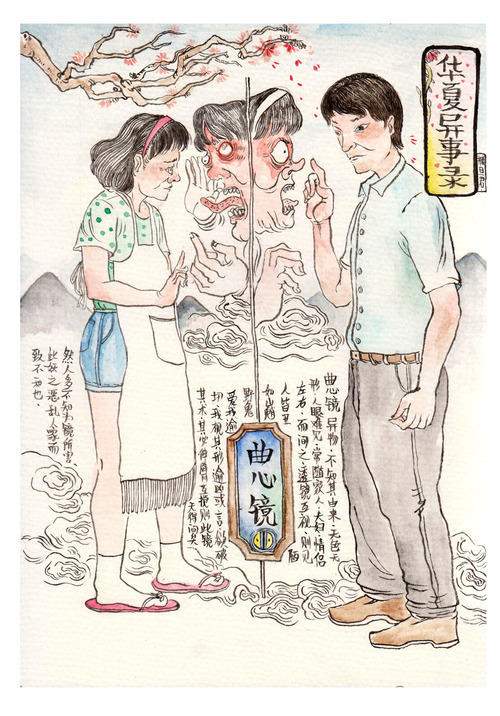

13. 朱八戒口吐黄金的消息,不到半日,早已传到纸币国京城内外,国舅杨天禄听得此情,急忙进宫去见妹子当今熙宗皇后黛玲娘娘。此时正当风和日丽,宫中鸟语花香, 只见熙宗皇帝御驾亲临百鸟亭,指手划脚正在训练众小鸟口叨纸币作出笼回笼上术,百花台上正坐着娘娘千岁,满身金饰,宝气珠光,但双眉颦蹙,含嗔带怒,似乎 有些不高兴,皇上整天只是弄着那些纸币,今见天禄笑嘻嘻迎上阶来,忙问道:“哥哥有甚快活事见告?”天禄即把朱八戒口叶[吐?]黄金的奇迹告诉了她。

In less than a half day’s time, the news of Zhu Bajie spitting up gold had reached the capital. Upon hearing this, the royal uncle, Yang Tianlu, hurriedly, went to the imperial palace to call on his younger sister, Empress Dai Ling, wife of Emperor Xizong. It was a pleasantly sunny day, with a calm wind. The palace was filled with the sound of birdsong and the fragrance of flowers. Emperor Xizong could be seen making his way to the Pavilion of Hundred Birds. Gesturing with his arms, he was training the birds to use their beaks to carry paper money in their mouths and fly in and out of their cage. Her majesty the Empress sat in the Pavilion of Blossoms, dressed in gold ornaments, with glistening jewels and shining pearls. Her eyebrows, however, were furrowed in displeasure, and her face betrayed anger. It seemed that she was rather unhappy about something. The emperor had spent the whole day playing with his paper money, so when the Empress saw Tianlu come smiling and laughing up the steps she hurriedly asked him, “Elder brother, whatever could it be that pleases you so much?” Whereupon Tianlu told her about the miracle of Zhu Bajie spitting up gold.

- This is a pointed barb at the rampant inflation that was made possible after the Nationalist government took China off the silver standard in 1935 and replaced it with the ‘fabi’ 法币. When war broke out with Japan in 1937, the government began printing money to cover deficit spending. Poor harvests and the outbreak of the Pacific War exacerbated the situation, so much so that inflation averaged more than 300 per cent between 1940 and 1946. Things only got worse as the civil war dragged on, so it seems probable the 1946 banning of Manhua Journey to the West stemmed at least in part from Zhang’s blatant criticism of KMT fiscal policies. See Albert Feuerwerker, “Economic Trends, 1912-49,” in The Cambridge History of China: Republican China, 1912-1949, Pt. 1, ed. John King Fairbank and Denis Crispin Twitchett (Cambridge University Press, 1983), 113–14. [↩]

- The historical Emperor Xizong (1119-1150) ruled during the short lived Jin Dynasty and oversaw campaigns against the failing Song dynasty. Another emperor whose name uses different characters, but is pronounced the same is Emperor Xizong 僖宗皇帝 (867-904), one of the final emperors of the Tang whose reign was threatened by agrarian rebellions which eventually led to the downfall of the Tang. Neither are particularly auspicious figures to be referencing. [↩]

- Likely a stand-in for Sun Yat-sen. [↩]

- Logically, then, this would be Chiang Kai-shek. [↩]