This morning I realized that September marked my tenth year of studying Chinese. It’s put me in something of a reflective mood, so bear with me while I reminisce (or feel free to go watch this video of a porcupine eating pumpkins instead).

Ten years ago I had just started my third year of community college, where I was completing computer science pre reqs. Comp sci was a bit of a stretch for me, nerd though I am, since I’ve never had a very good grasp of math. So the simple answer I give for why I switched majors to Chinese is that I flunked out of calculus. (Although it might be just as fair to say I flunked calculus because I was studying Chinese.)

I’ve always liked computers though, for making obscure information accessible—being able to Telnet to my local library was just about the coolest thing ever, and I’m probably one of the only people in the whole world who’ve read Encarta CD-ROM encyclopedia from end to end. (Before that, all I had was a set of 1968 World Books that didn’t mention the Civil Rights movement.) After that it was Geocities and Livejournal and—glory of glories—Wikipedia.

Chinese started out as a whim, based on the fact that I had read that it was one of the harder non-European languages. Comp sci required me take two years of a foreign language, and despite the fact I’d already spent a year in Germany, and studied several years of Spanish and French, I wanted to challenge myself to learn something further removed from English. And, as a bonus, back in 2005, China was in the news in big way and it seemed like picking up a basic competency would be a good way to improve my future job prospects.

More broadly, I think I was also attracted to the idea of finding an unknown place. Robinson Crusoe was one of my favorite books growing up, along with The Little Prince, and the movie version of Lawrence of Arabia. My dad had spent a gap year bicycling around Europe back in the 1970s, and I think that inspired me in a big way, too. And then while I was living in Europe myself I got into the Beats—Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Burroughs, especially. When I got back to the States I became obsessed with the idea of radical simplicity, thanks in large part to the pamphlet Fighting for Our Lives which an ex-girlfriend had sent me. I dropped out of school and moved to an organic farm on the East Coast, where I spent a year trying to decide what I wanted to do with my life.

Eventually I got the idea of trying to backpack from Bangkok to Yunnan, but ended up running out of money in Phnom Penh. After a couple of desperate months teaching English in Cambodia I’d decided it was time to go home and try something new. It’s a fun story to tell now, but at the time I remember being absolutely terrified. I was broke, and I’d become convinced that my family was going to end up footing the bill to life flight me home after getting into a traffic accident or worse. It wasn’t an especially rational fear, I’ll acknowledge, but in hindsight it got me thinking about the fact that privilege it not really something you get to accept or reject. Privilege is about family, it’s about where you are born, the way you speak, not just the way you interact with the world, but the way the world interacts with you.

So I would like to think that dedicating my life to studying (and now translating) Chinese has been about continuing to work from a position of privilege to create social change. The ideological struggle of the 21st century is arguably cultural homogeneity vs heterogeneity. A Starbucks on every corner and an iPhone in every home, but also bubble tea and taco trucks on every other corner and Chinese and Korean and Latin American science fiction in every home, too. I think this ties into the fight against climate change, which is really only the second existential global crisis we’ve faced (the first being the atom bomb). Fossil fuels and the infrastructure that supports their extraction and consumption are the epitome of big business. But cultural production and consumption (arguably) represent a different kind of business, one that is potentially much more sustainable given how many humans we have running around on the planet these days.

We’ve been given an amazing gift of a brain that thinks and learns and yet most of us spend our time engaged in mundane tasks, buying things we don’t need with money we don’t have. And even worse, we’re destroying the planet to do it.

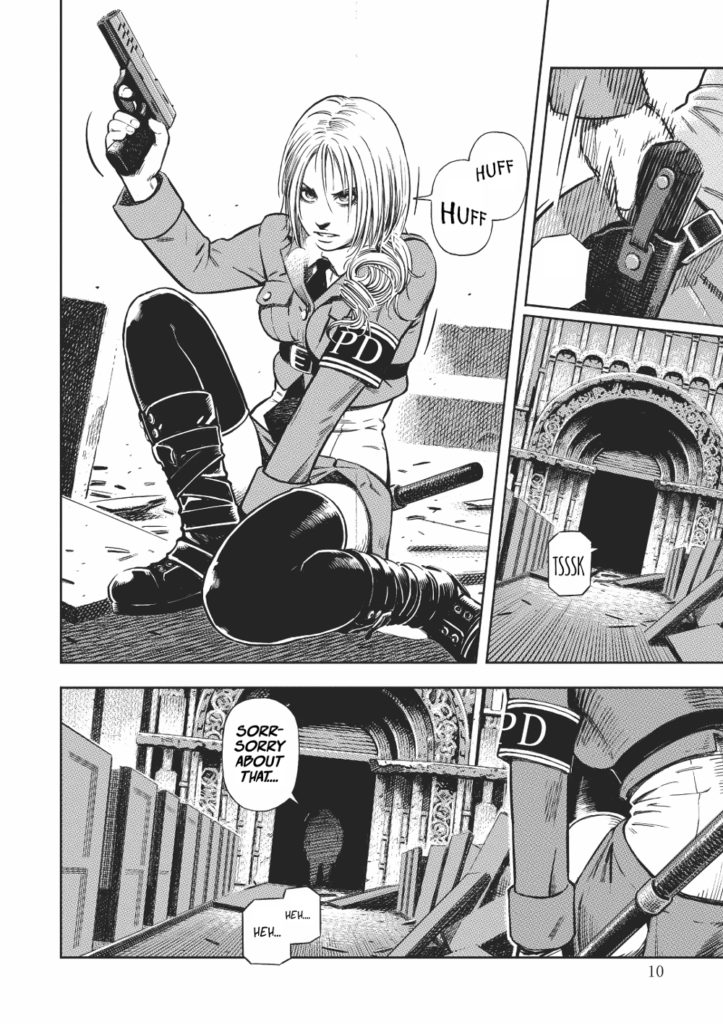

I’d like to think that we can turn the corner on this thing, and that my small contribution will be measured in words and pictures, rather than in dollars and carbon. There is no shortage of coverage of China in the news, but so little of it is of real substance. The average American doesn’t understand China because they don’t ever get a chance to. China isn’t tea and Beijing opera and kung fu, nor is it smog, corruption, and a growing income gap—or rather, it is all those things, but also a lot of other things, too. Real Chinese voices are diverse. They don’t always agree with each other. A great number of them don’t even live in China.

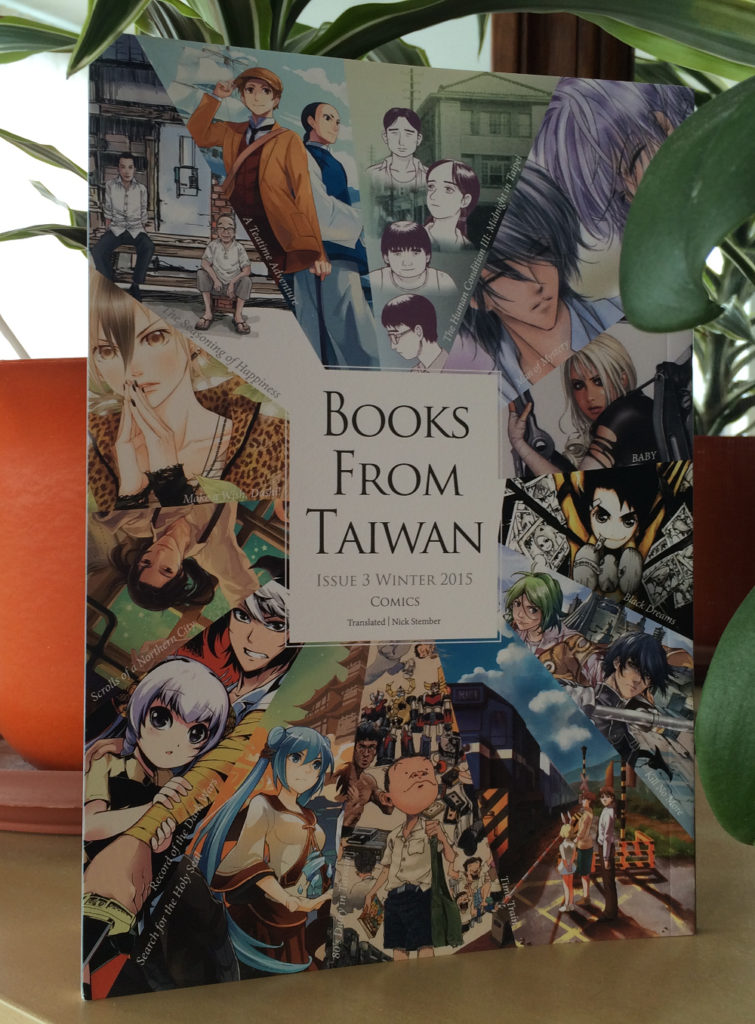

So, in the spirit of sharing an alternative voice, and something I made, rather than bought (just in time for Christmas too!) I tracked down an old project of mine that’s been sitting in a desk drawer for the last couple of years. (There are also a couple dozen print copies floating around, and at one point you could check it out from the Multnomah county zine library. Alas no more.)

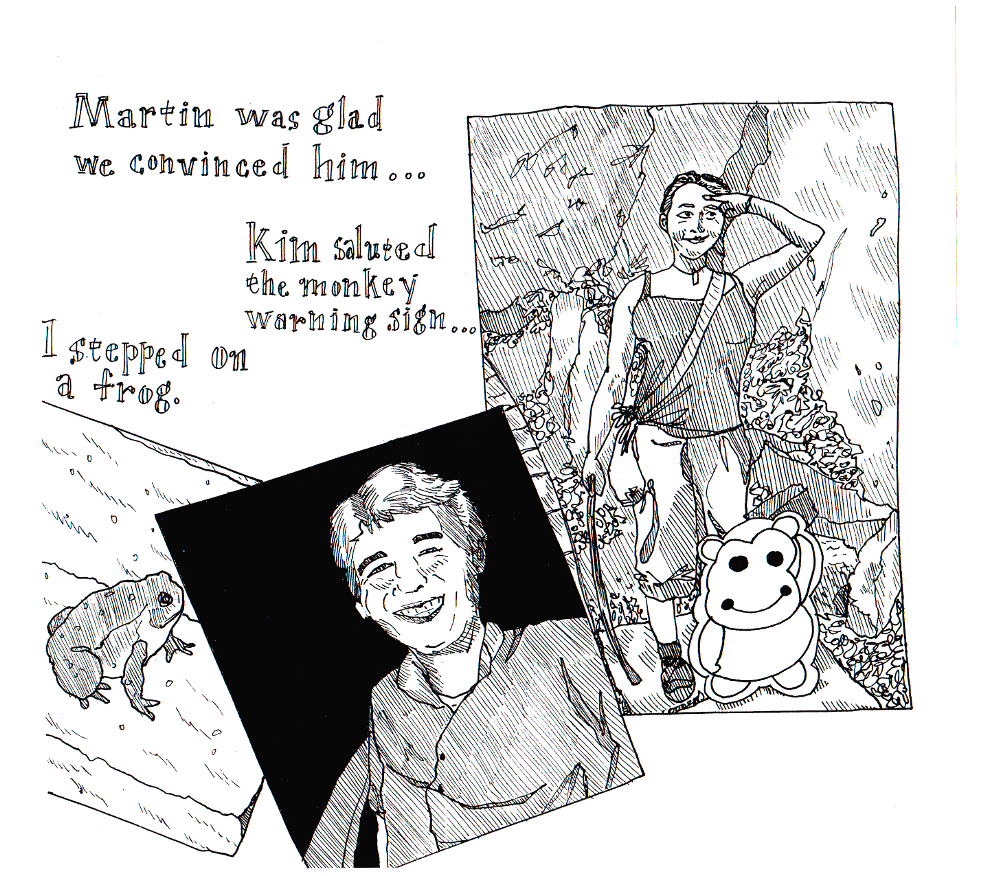

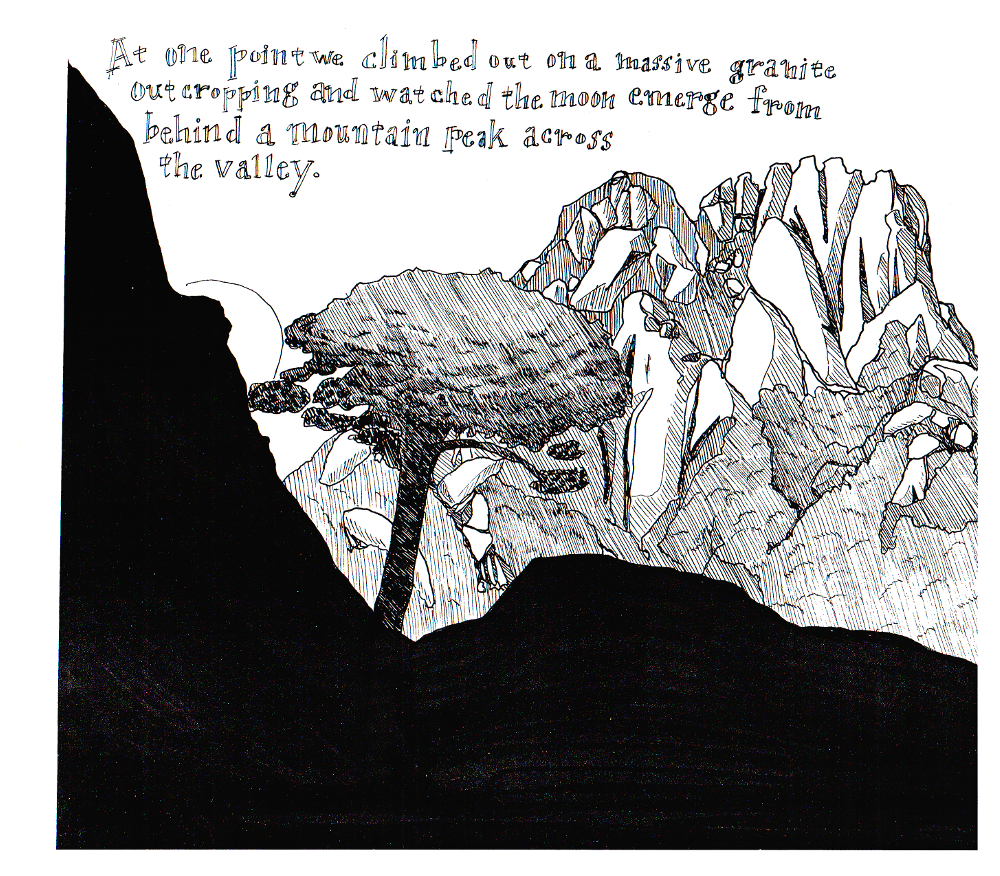

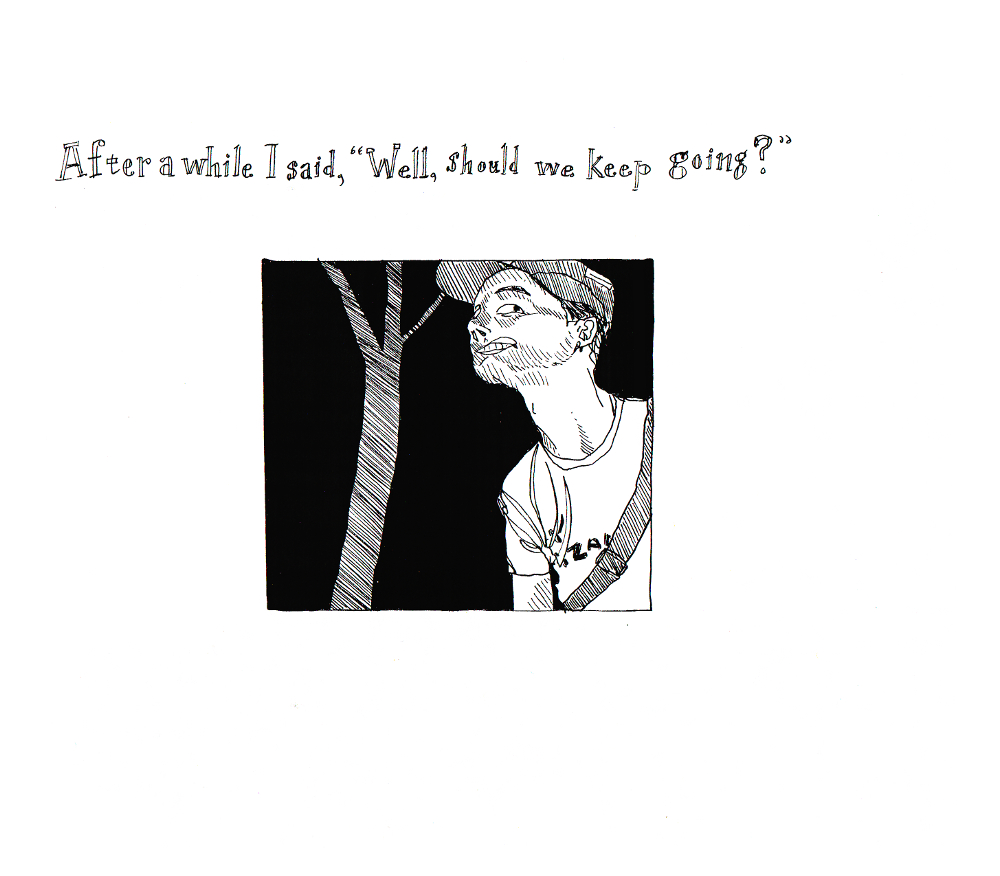

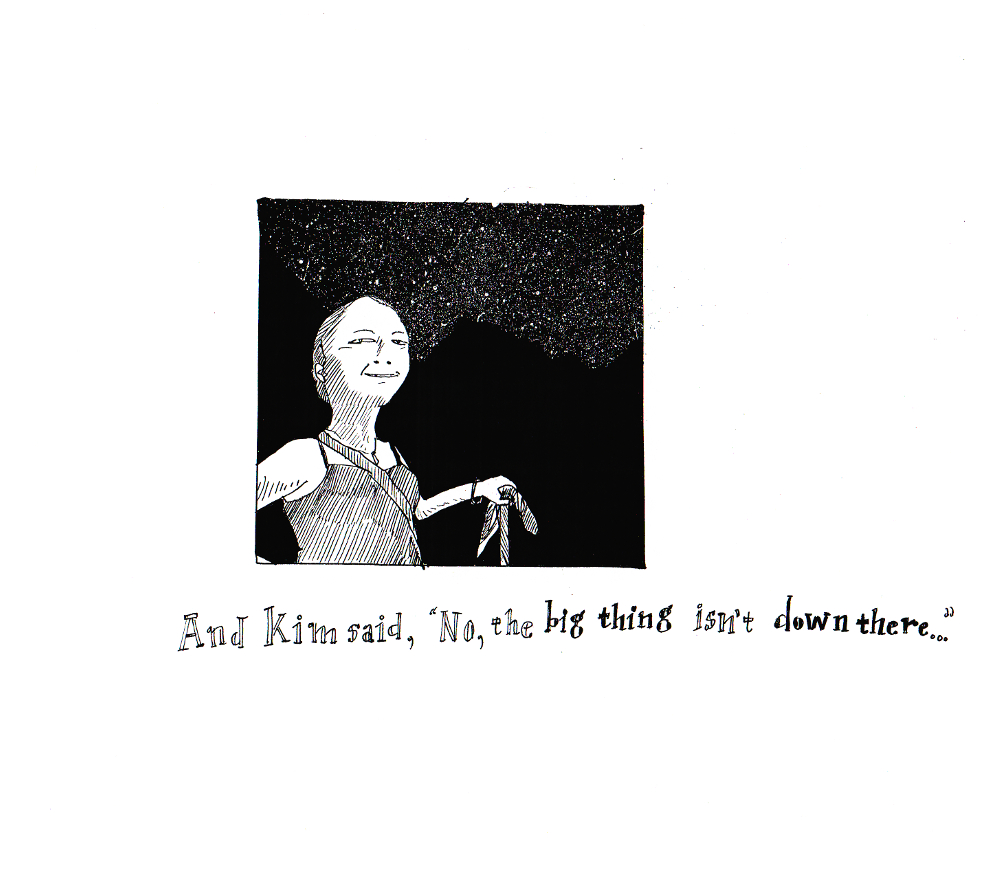

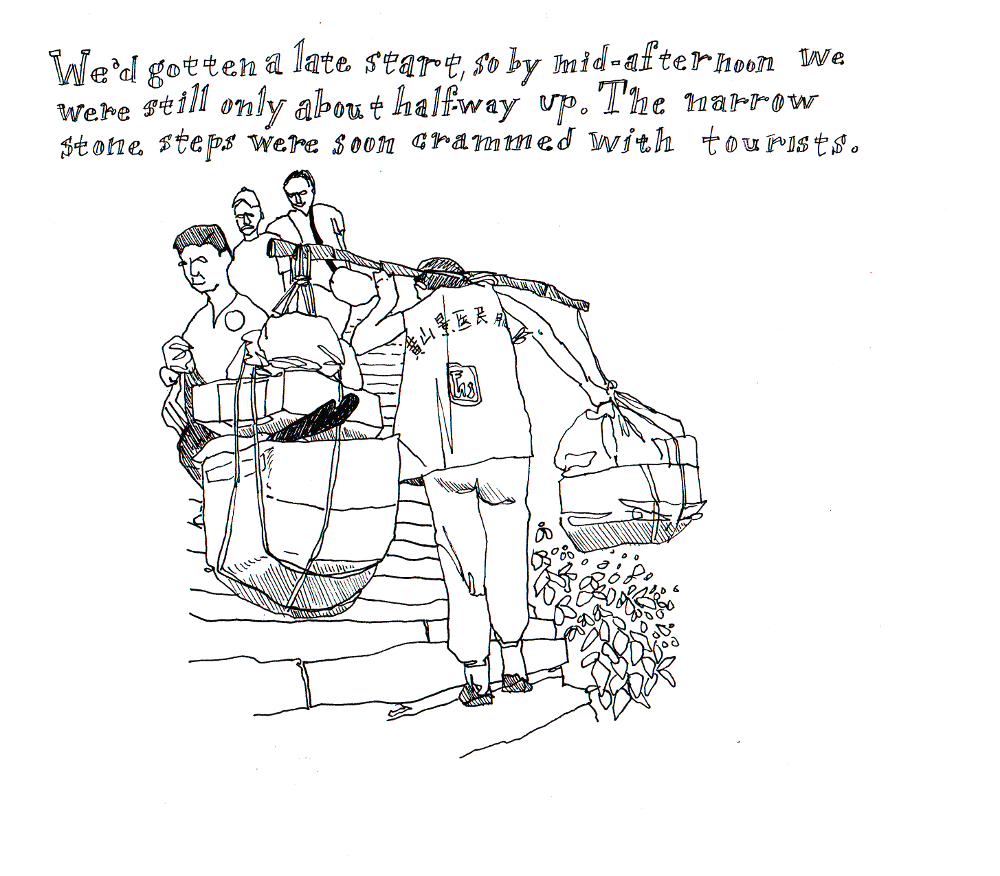

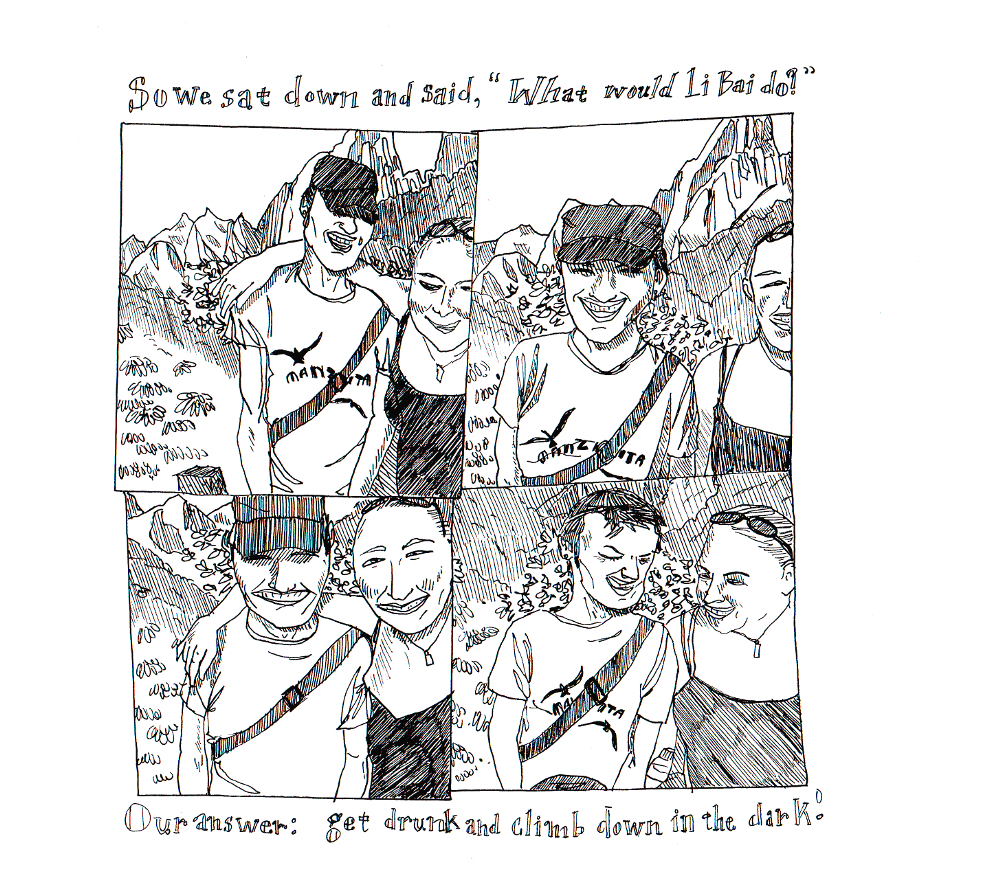

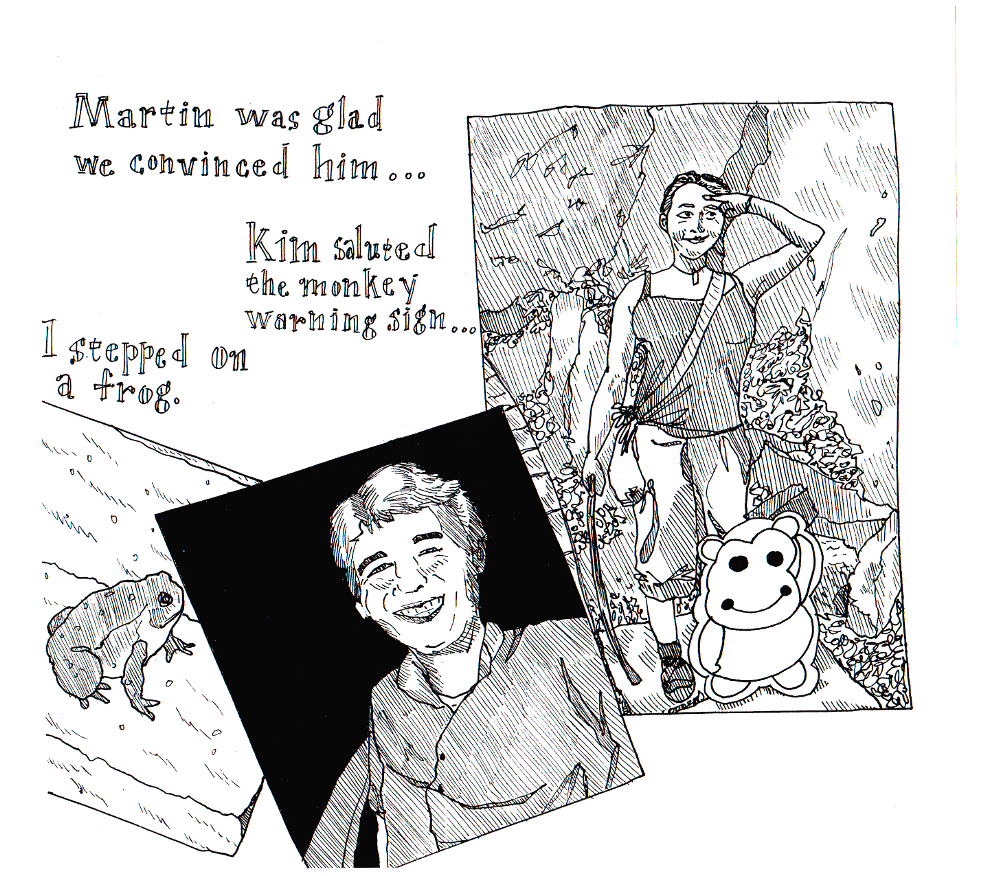

At the end of my first year studying abroad in Harbin, I lucked out and got to spend a month seeing the sights with my fellow China nerd, Oregonian, and BFF Kim. Kim had been planning the trip with Martin, a German China nerd who she met in Beijing, and they were generous enough to let me tag along. We climbed mountains, visited Qufu, where Confucius was born and buried, toured the Tsingtao factory, and got lost in Shanghai. In short, it was the kind of trip you can only have when you’re in your early twenties and have China on the brain.

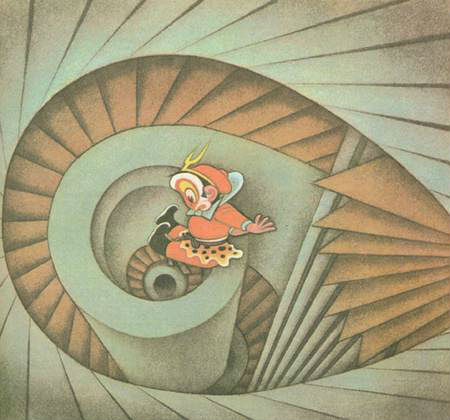

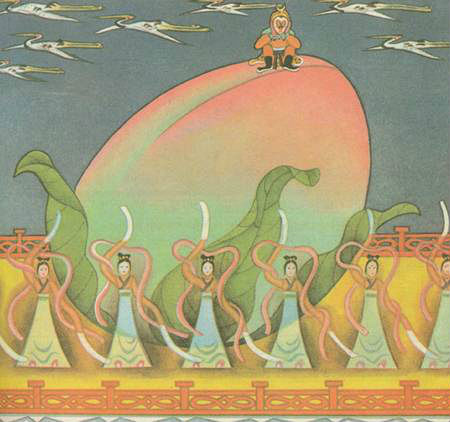

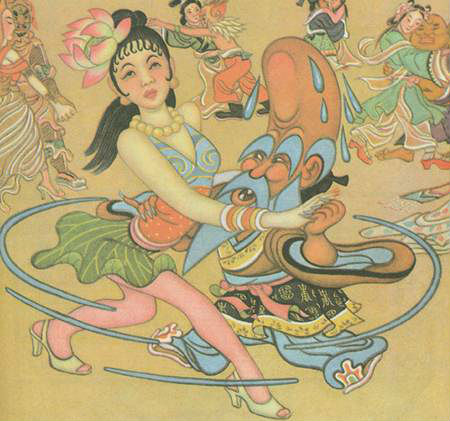

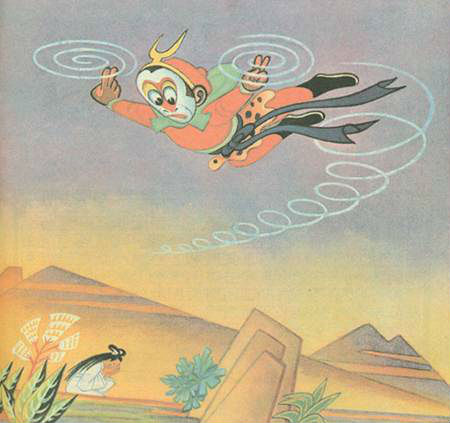

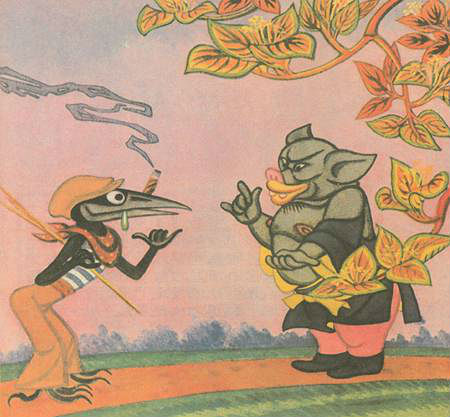

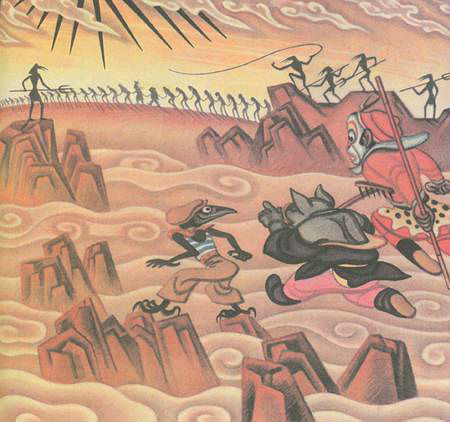

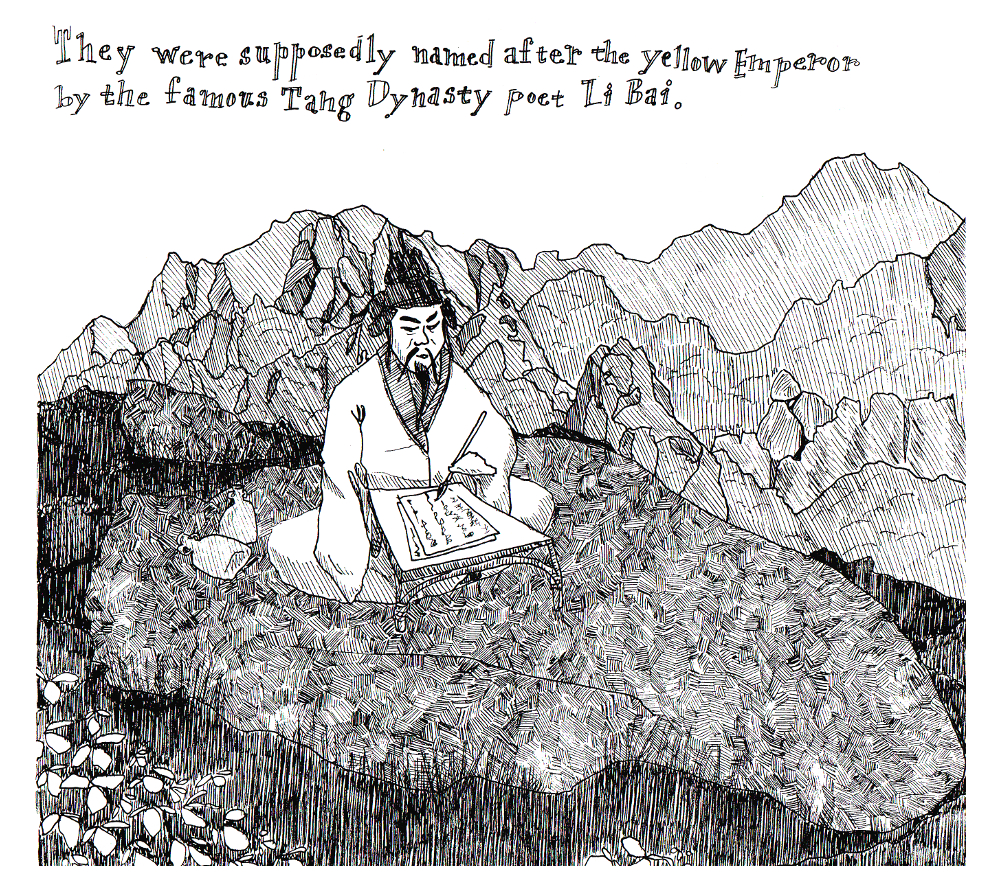

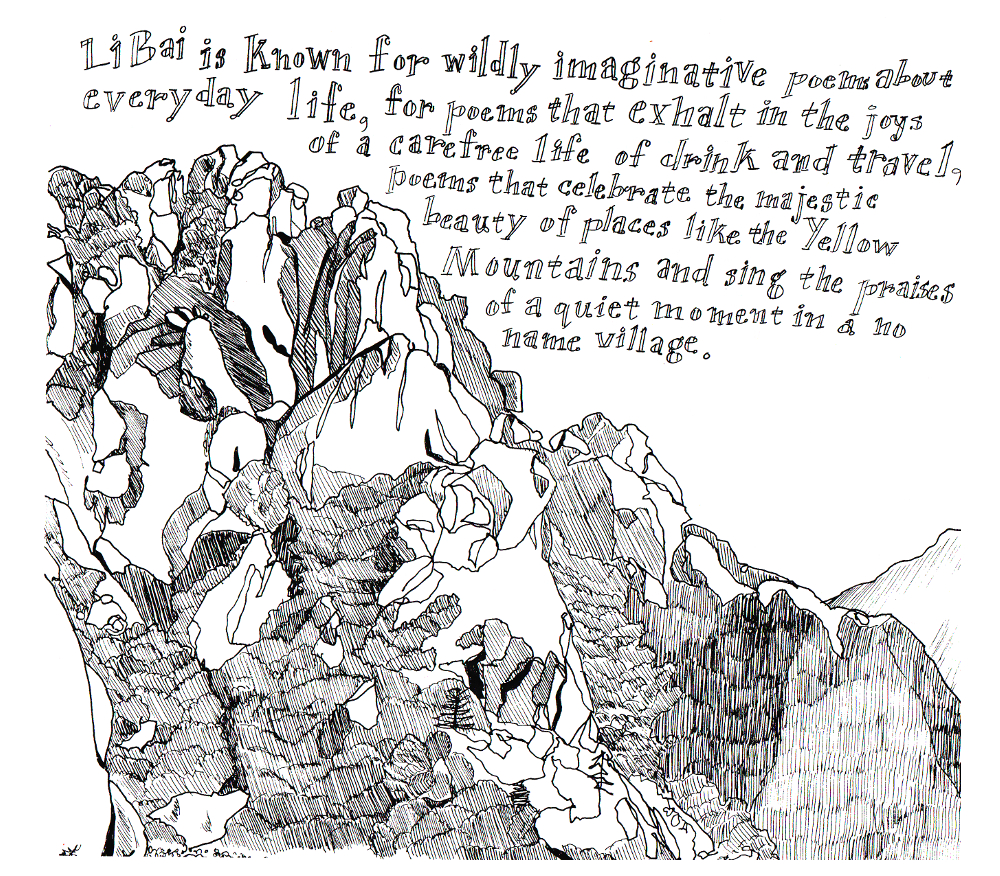

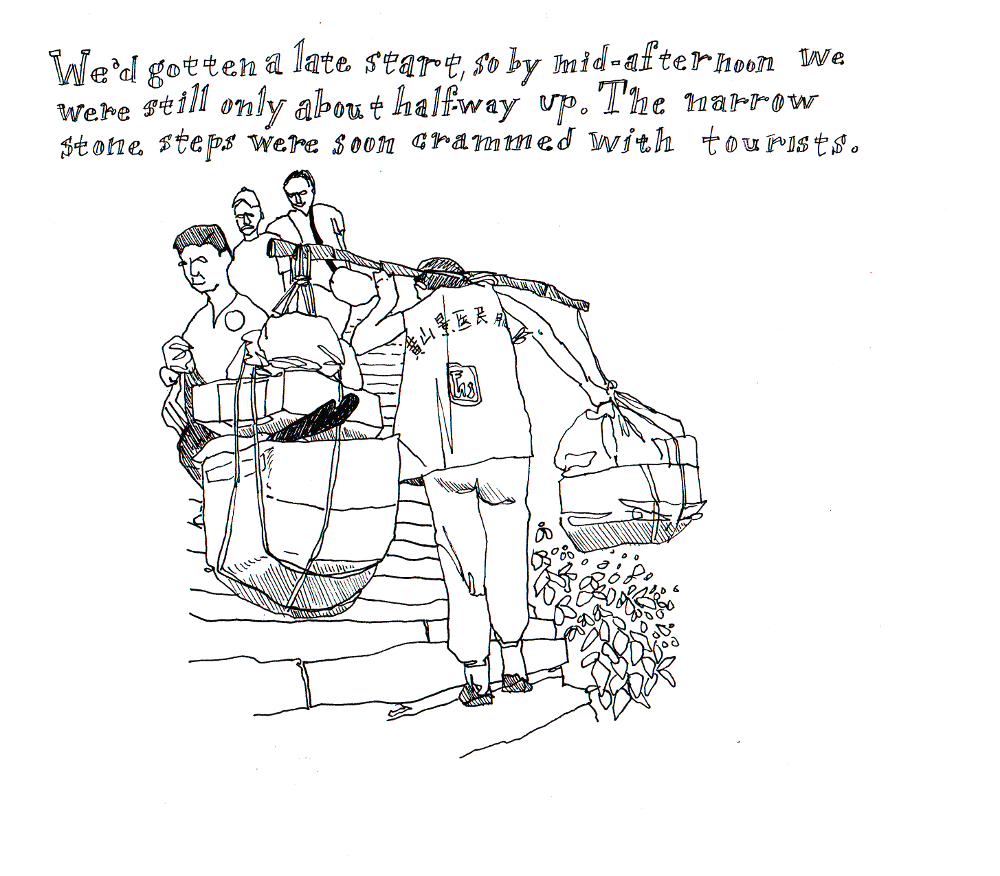

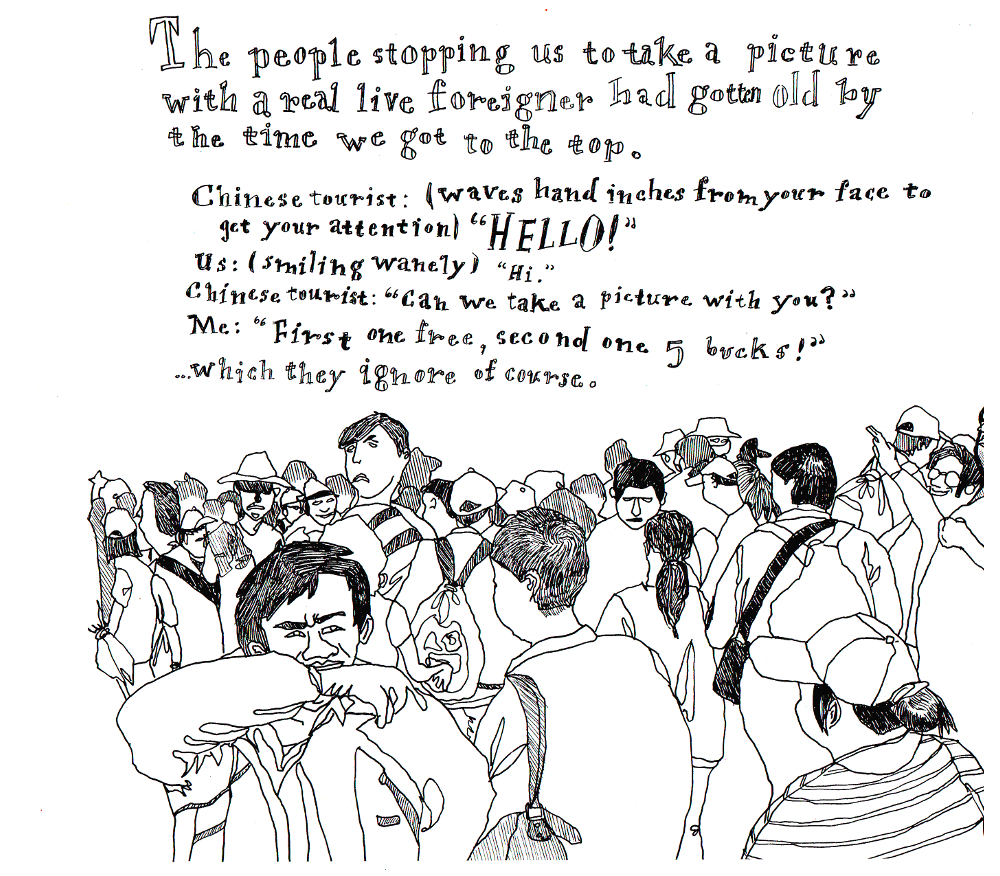

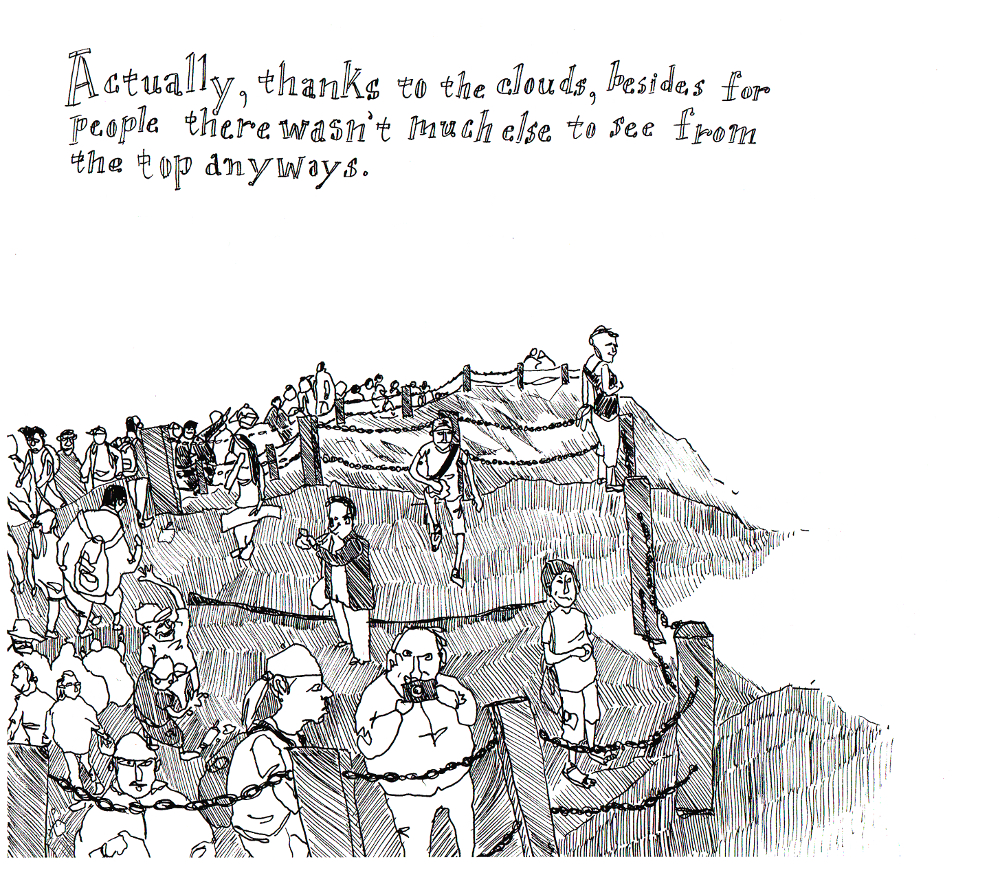

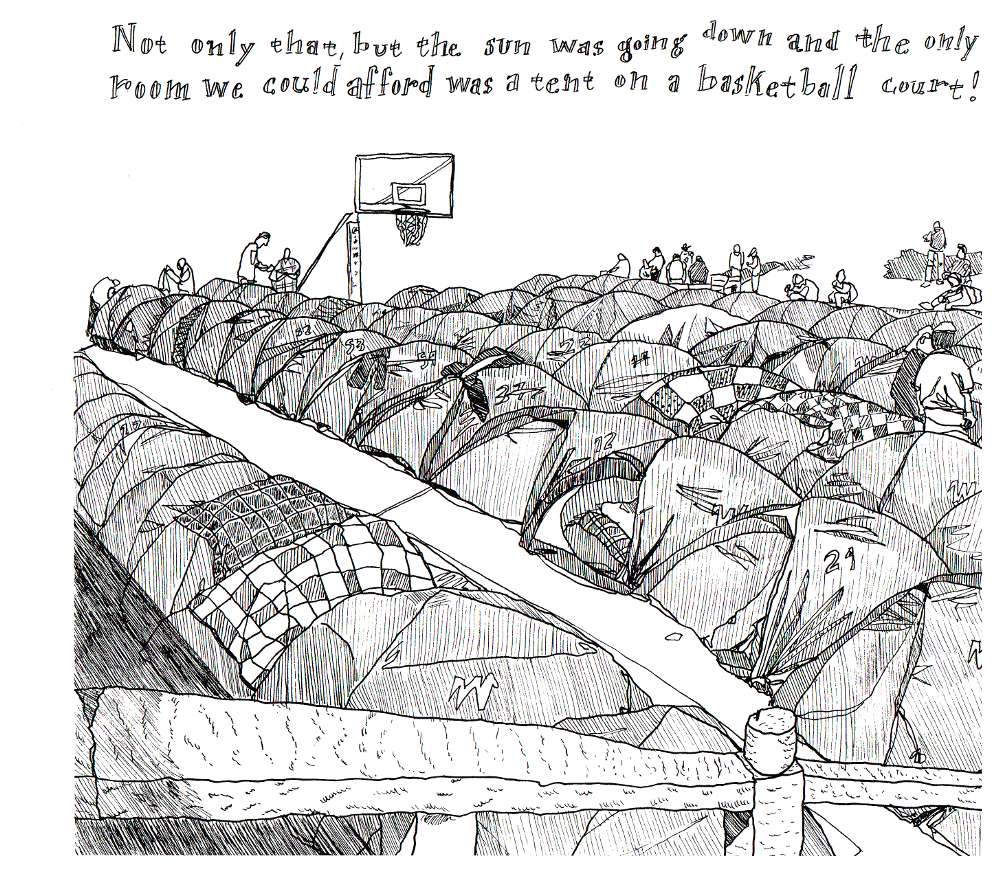

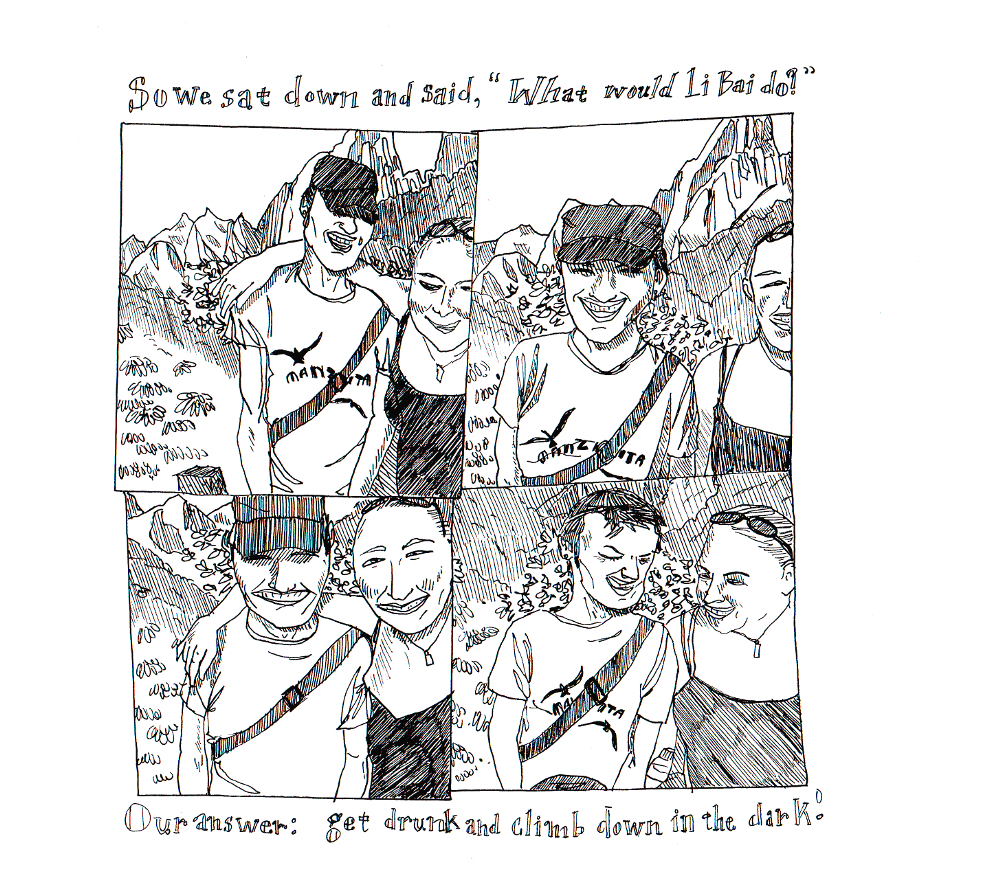

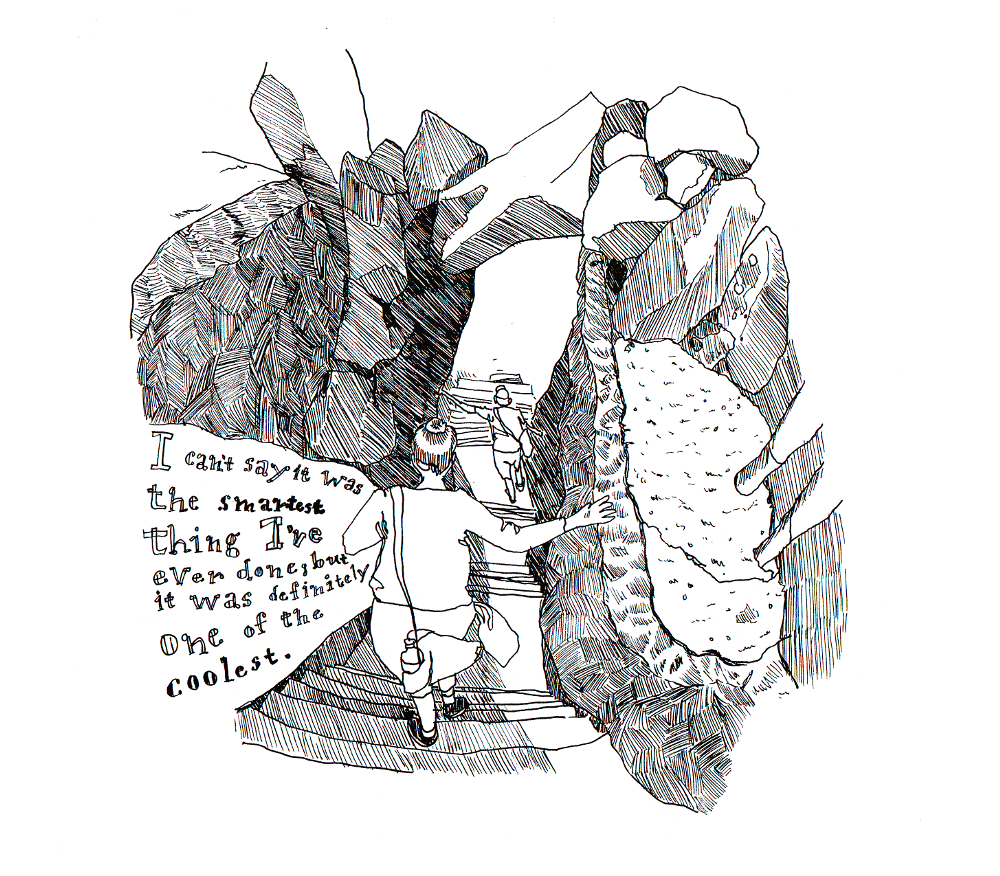

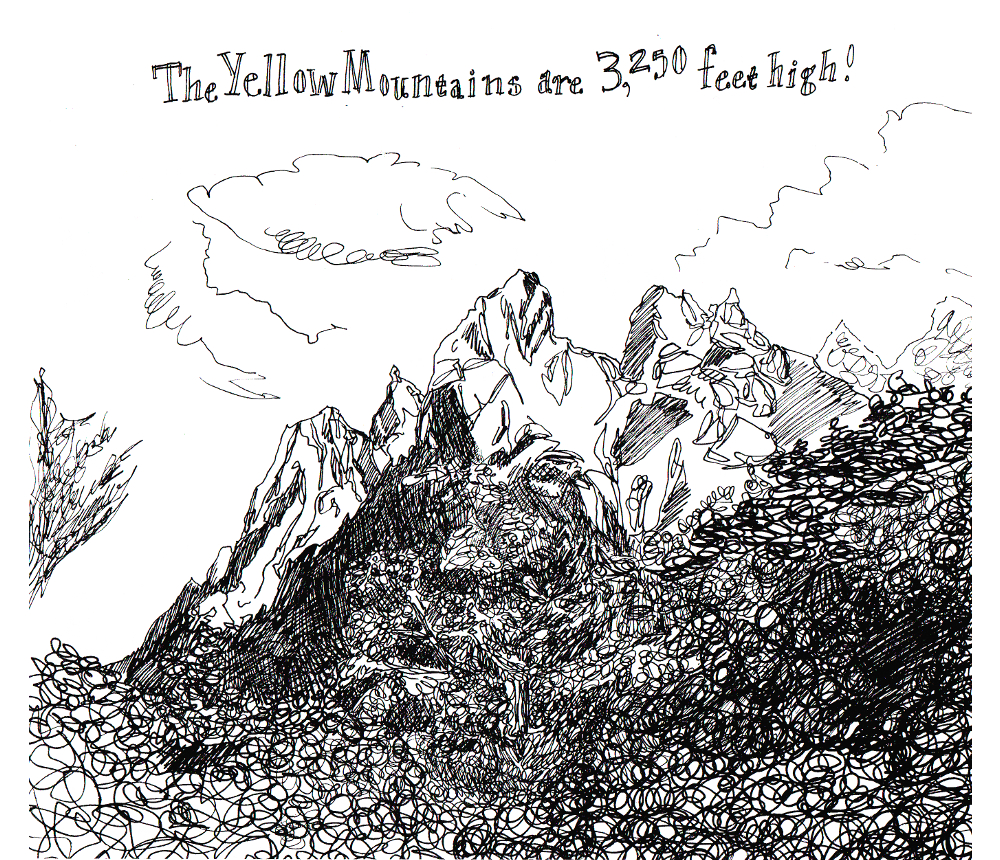

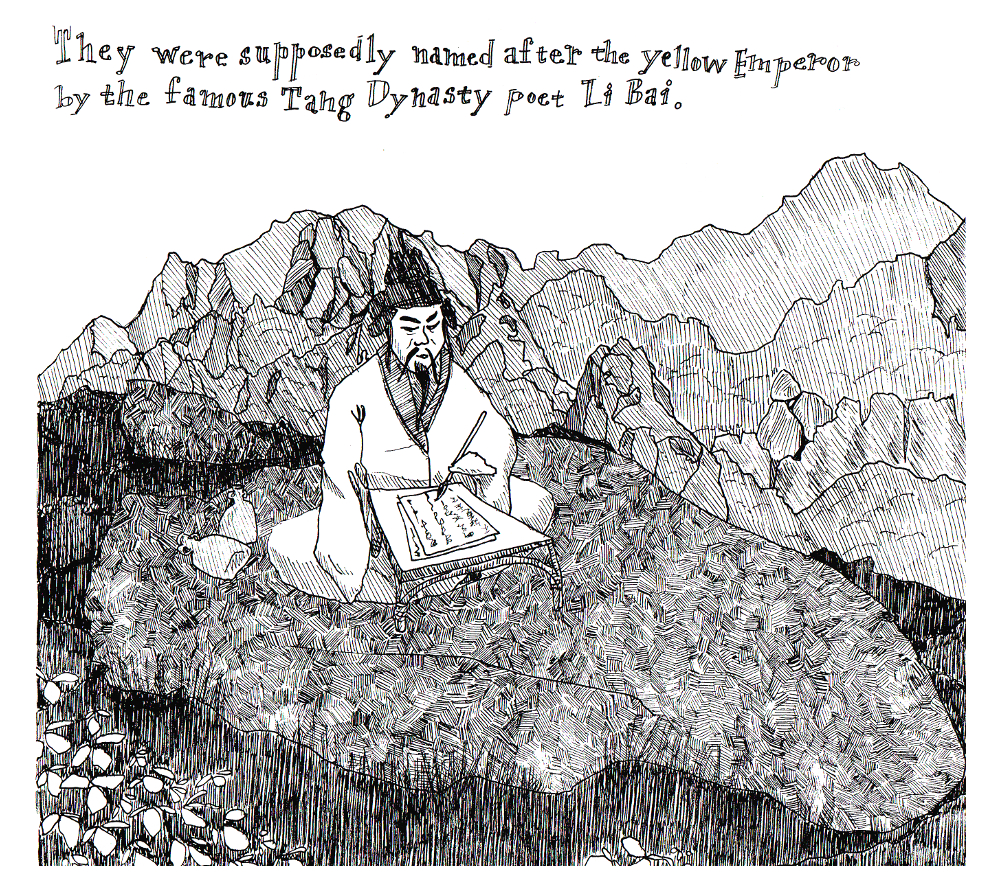

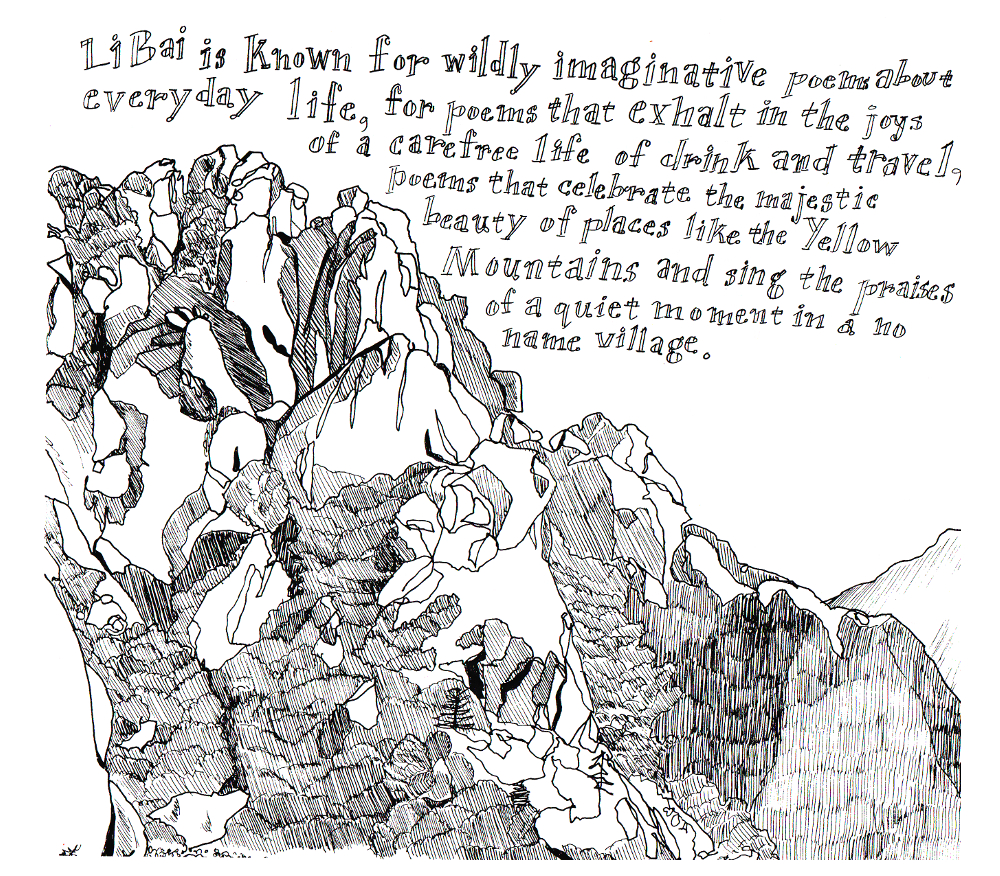

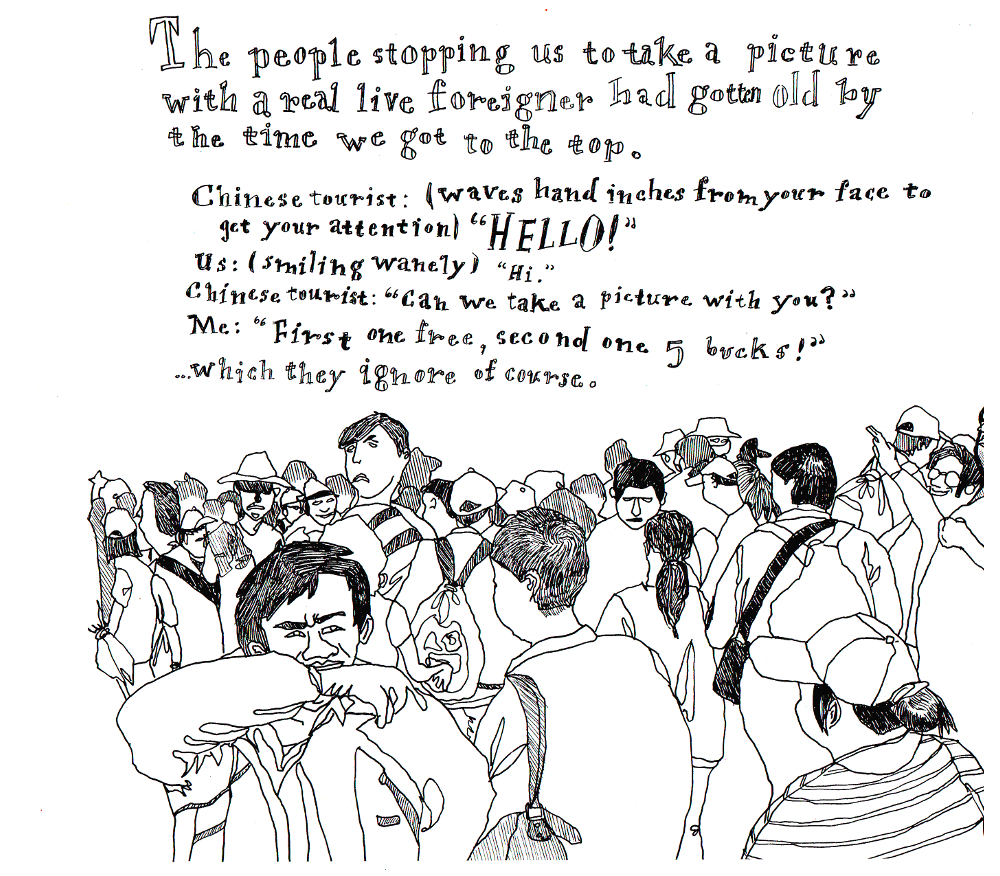

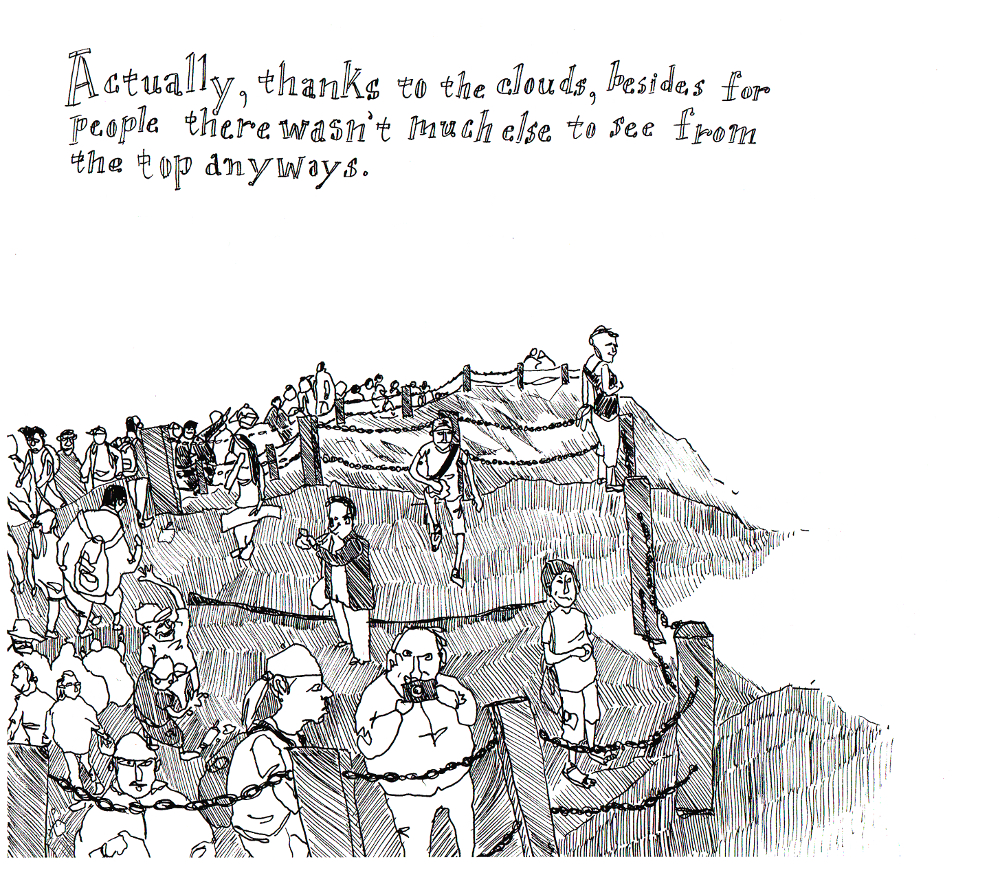

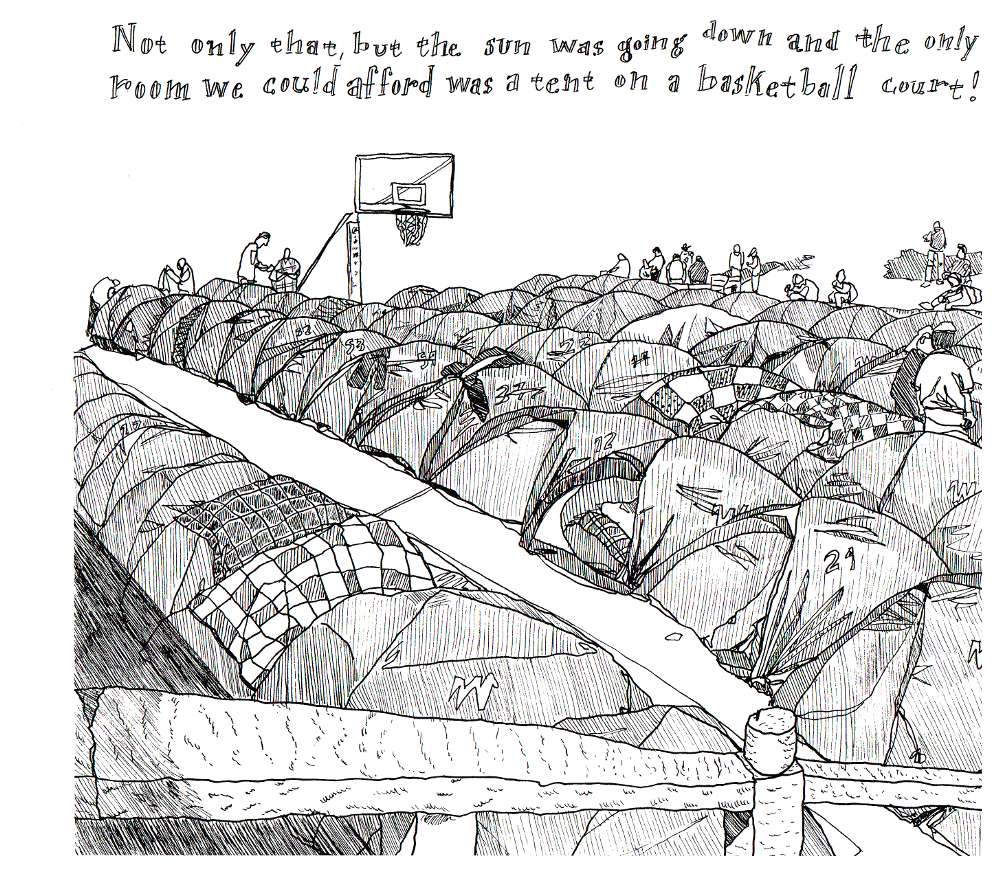

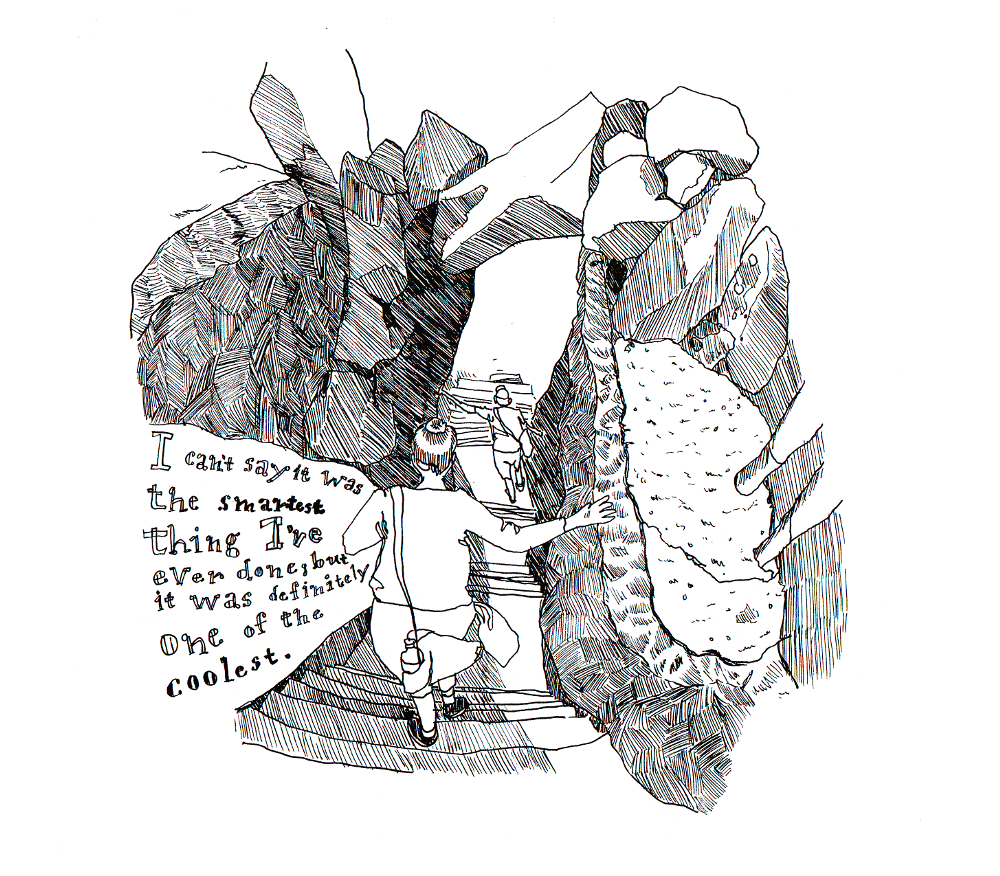

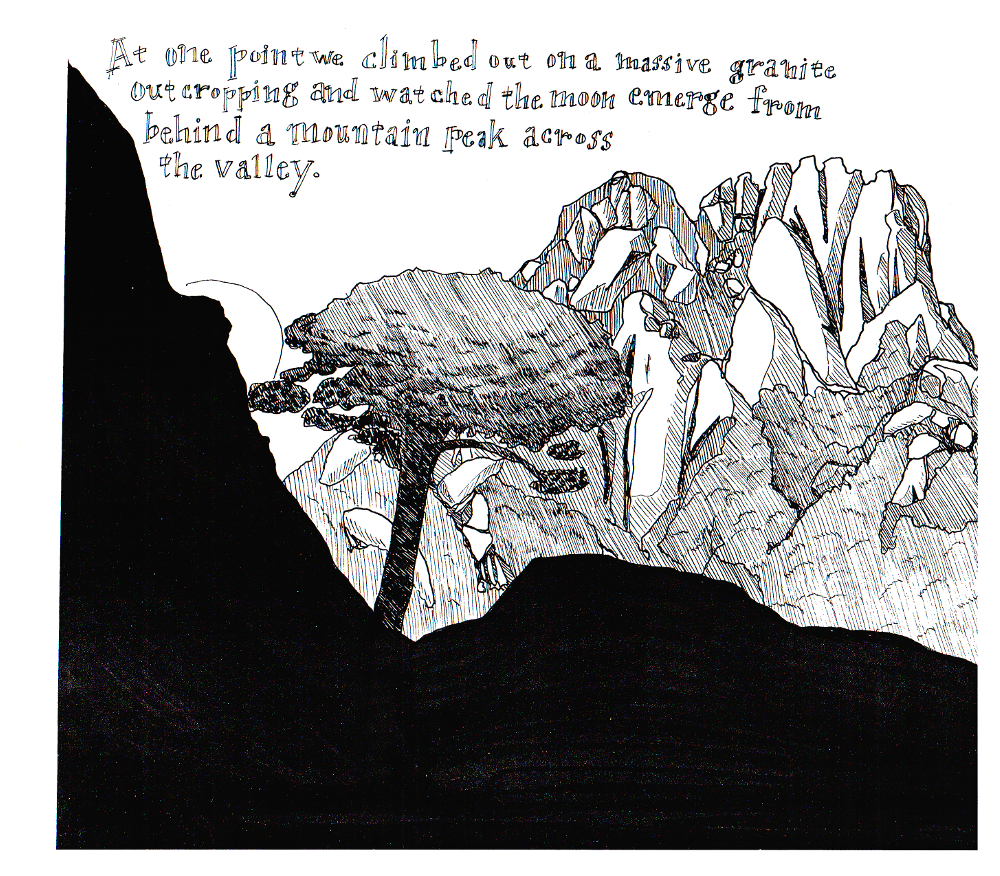

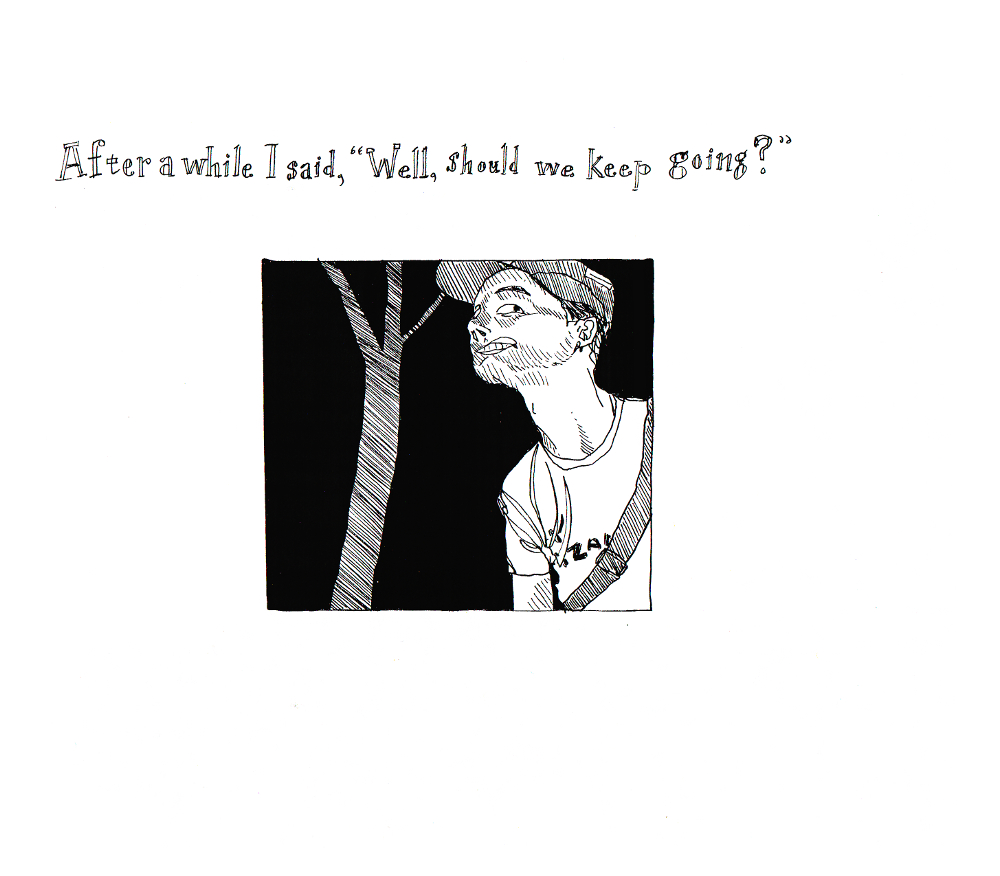

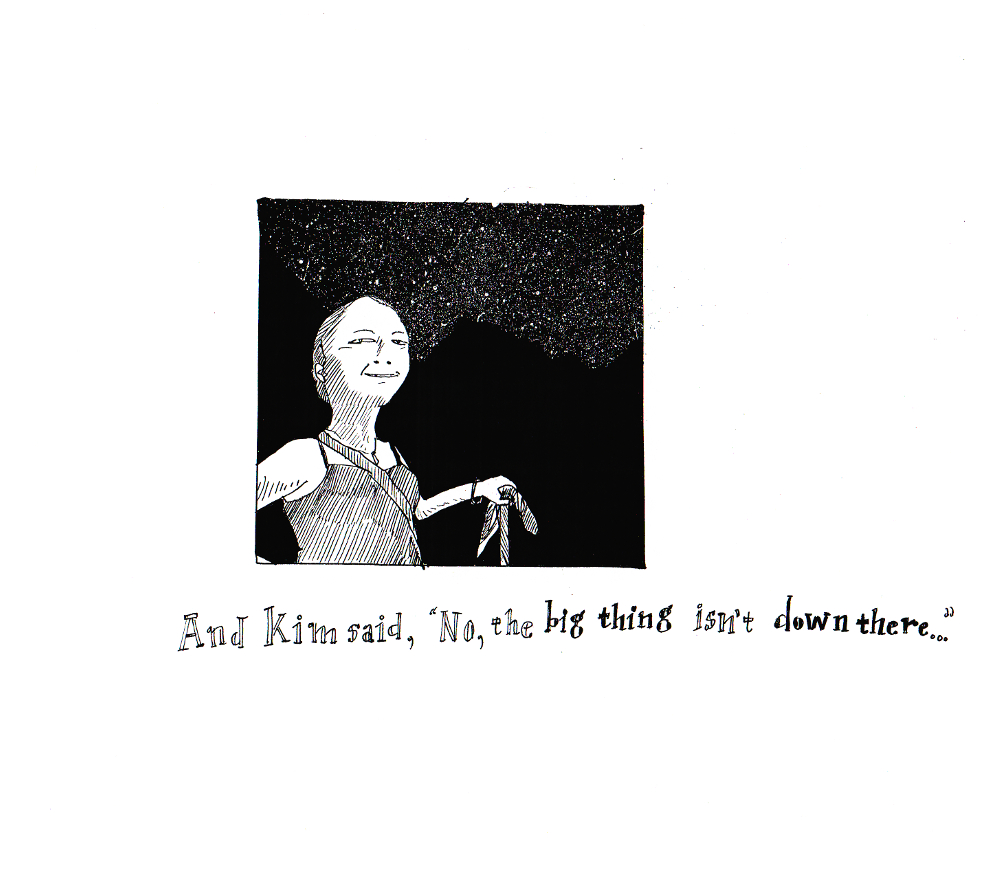

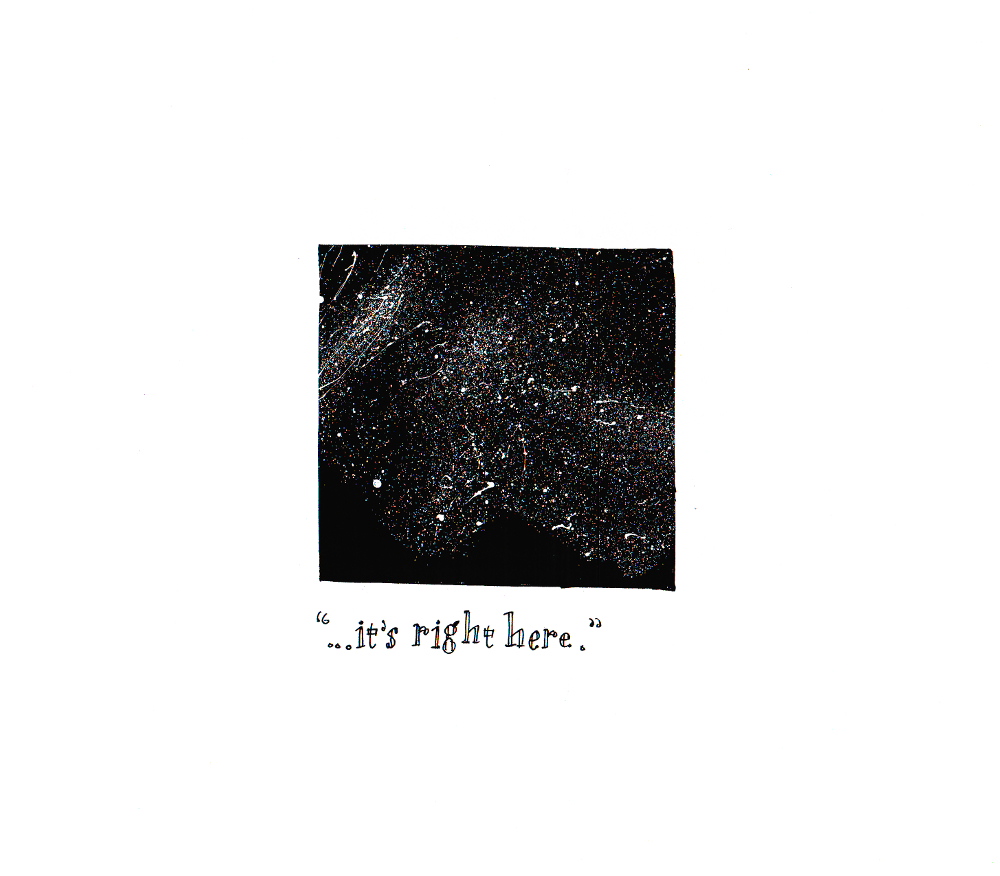

Two years later I self-published a short comic about one of the more memorable incidents from the trip, on Huang Shan (aka Yellow Mountain):

Okay, so maybe not a masterpiece, I admit! But I’ve been thinking a lot about this comic lately, and the spirit of generosity that went into it. I didn’t make any money from it, but I made a lifelong friend—Nim, the founder of Research Club, was sitting next to me at the Portland Zine Symposium and we bonded over stories of misspent youth and art making. That led to a whole circle of artists and zinesters that I ended up spending my last year in Portland with, before heading back to China in 2010.

My second Chinese experience was amazing too, in a different way—I got back together with Ding, and we built a life together in Shanghai. I had my first adult job, with suits and everything! But I also made sacrifices that I didn’t need to make. I mostly stopped drawing and writing comics. Life got simpler, but it didn’t get easier. Going back to school was a part of that process of finding a way to make a living but not let the bastards grind me down, so to speak.

I feel lucky for all of the opportunities that studying Chinese has given me, especially now that I find myself (miraculously) gainfully employed as a translator of Chinese comics and sci-fi, among other things. I don’t think I would have predicted that I would end up here, though, and it’s hard to say how long it will last. Sometimes I feel like life is more about finding out what you don’t want to do that it is about finding what you do want to do (or can make a living doing). I used to think that once you found it you were done, but now I’m starting to realize that it’s a constant process, shaped not only by opportunity and privilege, but by consciously spending your time doing this and not that.

It’s about finding that big thing and seeing where it takes you.

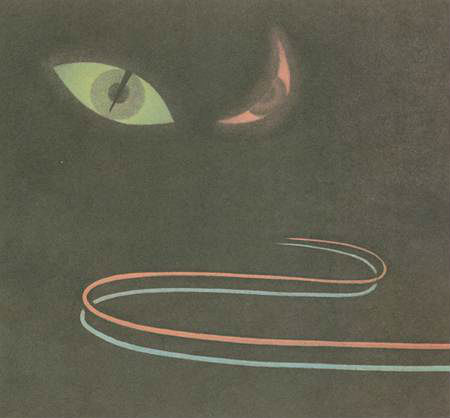

![Monkey, 1st edition cover [front]](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/image001.jpg)

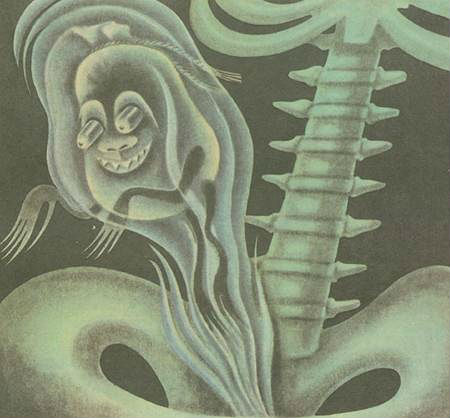

![Monkey, 1st edition cover [back]](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/image003.jpg)