This is the fifth chapter in my MA thesis, The Shanghai Manhua Society: A History of Early Chinese Cartoonists, 1918-1938, completed in December 2015 at the Department of Asian Studies at UBC. Since passing my defense, I’ve decided to put the whole thing up online so that my research will be available to the rest of the world. I’ve also decided to use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can share it with anyone you like, as long as you don’t charge money for it. Over the next couple of days I’ll be putting up the whole thing, chapter by chapter. You can also download a PDF version here.

Since no former member of the Manhua Society has gone on record to explain why the Manhua Society gradually drifted apart in late 1927 and early 1928, I looked at the evidence left behind and reconstruct a plausible sequence of events, like a crime scene investigator using various clues the perpetrators left behind. That no Manhua Society member has seen fit to comment on the dissolution of the group seems strange, given the importance placed on its formation as, in the words of Bi Keguan, “the first civil cartoon society in Chinese history.”[1]

From the evidence, it seems that at least in part an internal schism (or schisms) broke the group apart from the inside. For one, the checkered relationship between Ji Xiaobo and Ye Qianyu seems to have colored his interactions with the rest of the group.[2] Lu Shaofei, on the other hand, seems to have had an especially close relationship with Ji up until late 1929, when the Ji seems to have mostly stopped publishing cartoons after being hired as a censor for the Ministry of Education.[3] Huang Wang also withdrew from the group, and the cartooning world in general in the spring of 1928 after a falling out with Zhang Zhengyu, publishing leftist cartoons two years later under various pseudonyms, while Ding Song, meanwhile, seems to have distanced himself from the group following an obscenity trial in late 1928.[4] Finally Hu Xuguang seems to have quit cartooning entirely in 1928, finding employment as set decorator in the film industry instead.[5]

At the same time, while it is true that four prominent members of the Manhua Society (Ji, Wang, Ding Song, and Hu) left the group to pursue other projects, as did other more minor members (Zhang Meisun and Cai Shudan), the bonds between the remaining five members of the Manhua Society (Ye, Huang, Zhang, Zhang, and Lu), however, seem to have grown even stronger throughout 1928, while at the same time allowing new collaborators to emerge. This reflects the fluid nature of membership in the Manhua Society that is attested to in their early meeting notes which note that, “…our group has adopted an open format and we welcome new comrades to join. There is no established procedure for soliciting new members, so interested parties are encouraged to contact us” 該會取公開態度、歡迎同志加入、但無徵求會員之手續、願入會者、可與該會接洽云.[6]

Shanghai Sketch I

To understand the breakup of the Manhua Society, we need to go back to the summer of 1927, just after the arrival of the Northern Expedition in Shanghai that spring. Having spent June and July of 1927 in Fuzhou, the provincial capital of Fujian (some 250 kilometers north of Xiamen) Ye found himself without a job. In December, his former boss in the Political Office of the Navy recruited him to create an illustrated magazine mocking British imperialism in support of a trade union strike at British-American Tobacco. Ding Song and Zhang Guangyu were both working at BAT at the time, Zhang having left his job as an industrial designer at the Chinese-owned Shanghai Mofan Factory in early 1927. Ye recruited Wang Dunqing to help create content for the magazine, focusing on the Opium Wars. Although the protest was ultimately suppressed by BAT management, the first issue of their magazine (which ultimately took the form of a broadsheet) seems to have been a success. According to Ye, however, just as they were preparing to publish a second issue, however, the KMT government stepped in and shut them down. [7]

This collaboration led to the creation of a new publication in late 1927, with the addition of the newly unemployed Huang Wennong, called Shanghai Sketch. “At the time, there were three of us working together: Huang Wennong provided the drawings, I was charge of doing all the odd jobs, and Wang Dunqing was in charging of editing.” 當時我們三人合伙,黃文農供畫,我管跑腿,王敦慶管編務.[8] ‘All the odd jobs’, in this case seems to mean taking care of printing and distribution. If one looks at the announcements posted in the Shenbao, and the actual publication itself, however, it is clear that Ye contributed a great deal of his own art, in addition to his other responsibilities:

A DATE HAS BEEN SET FOR THE NEW PUBLICATION SHANGHAI SKETCH

Manhua Society members, Wang Dunqing, Huang Wennong, Ye Qianyu, three united comrades from the world of art and literature, will be distributing a pictorial magazine that uses five-color rubber blanket offset printing. Every three days a new issue will be released under the name, “Shanghai Sketch.” The objectives of this periodical are to use words and pictographic art to encourage Chinese industry, beautify present day society, and conduct the revolutionary spirit. The contents of each issue will be one set of long-running humorous cartoons, and one set of short-running cartoons. The beautiful printing will include more than 20 satirical drawings, joke drawings, etc. while he text will include miscellaneous social commentary, short stories, interesting accounts, etc. Regarding the preparation of the pictographic materials and the selection of texts, there has already been over a year of preparation so the works we will publish are, without exception, vastly different from those published in normal pictorial magazines and three-day papers. This periodical will be published December 31, Year 16 [1927].

新刊上海漫畫出版有期

漫畫會會員王敦慶·黃文農·葉淺予·三君、集合文藝界同志、將發行一種畫報、以五彩橡皮版精印、每三日出版一期、命名“上海漫畫、”其宗旨在以文字及圖畫藝術、主吹國內工業、美化現有社會、傳導革命精神、逐期內容、有長期及短期滑稽活動畫各一套、美的裝束畫諷刺畫笑畫等約二十餘幀、文字方面、有社會雜評短篇小說及富有趣味之記載等、對於圖畫材料之籌備、文字風格之揀選、已達一年之久、故將來錄登作品、無不與尋常畫報及其他三日刊有所逈異、聞該報准定於十六年十二月三十一日出版。[9]

Five days later, the following notice appeared, which mentions that Ding Song and Zhang Guangyu were also attached to the project, in addition to the translators Wang Qixu 王啟煦 (pennames Wang Kangfu 王抗夫, Wang Yizhong 王藝鐘, Wang Jushi 王弆石, n.d.)[10] and Ji Zanyu 季贊育 (n.d.), and the artists Chen Qiucao 陳秋草 (1906-1988) and Fang Xuegu 方雪鴣 (n.d.) :

SHANGHAI SKETCH TO BE PUBLISHED REGULARLY

The soon to appear five-color “Shanghai Sketch,” will be serialized by Manhua Society members, Wang Dunqing, Huang Wennong, Ye Qianyu, together with comrades of the art and literature world, such as Ding Song, Zhang Guangyu, Wang Qixu, Ji Zanyu, Chen Qiucao, Fang Xuegu, etc. writing and editing. The content of the first issue will include Huang Wennong’s “Get on the Horse and Drop Anchor,” Ye Qianyu’s “Standard Sizes”, and new fashion drawings; Wang Dunqing’s “Long Live the Tramp” and “That Girl Man Yu”; and Wu Handu’s marvelous explanation for “Why the Revolution Has Yet to Succeed”, etc. The textual and graphic content will be by and large humorous, with an eye to improving readers’ vision, and the warm approval of society at large. This publication will be published January 1, Year 17 [1928].

上海漫畫定期出版

行將出世之五彩“上海漫畫”、係由漫畫會會員王敦慶黃文農葉淺予集合文藝界同志、如丁悚張光宇王啟煦季贊育陳秋草方雪鴣等、執筆編輯、其第一期內容有黃文農之上馬及拋錨、葉淺予之大小標凖及新裝畫、王孰慶之小癟三萬歲及曼瑜這姑娘、吳厂獨之革命尚未成功之妙解等、文字與圖畫材料均以幽默為主體、想可調劑讀者之眼光、而受社會熱烈之歡迎、該報准於十七年一月一日出版云。[11]

Given what we know about the publication, which only managed to put out one issue and featuring the work of the three founders, this announcement seems to have been an attempt to drive up sales by cashing in on the name recognition of Ding Song and Zhang Guangyu. The others seem to have been friends of Wang Dunqing, and may have been included for similar reasons.

The printing costs for the magazine were provided on credit, thanks to Wang Dunqing’s relationship with the printer. Printed as a single-side broadsheet designed to be folded into quarters, Ye Qianyu recalls that the publication was met with confusion by newspaper distributors who didn’t know how to market it.[12] Although illustrated broadsheets were common during the 1910s and early 1920s in Shanghai, most were double-sided, rather than single-side like Shanghai Sketch. Given the quality of the work, however, combined with the name recognition of Huang Wennong, it seems suprising that it attracted so little interest on the part of newspaper sellers.

According to a notice posted in the first issue of Shanghai Sketch, however, there was also a problem with the printer:

NOTICE FROM THE EDITOR

Daxin Printing Company, the press undertaking the printing of this publication, urgently requires the installation of new equipment. Therefore after publishing this issue, we must temporarily stop publication for one issue. We absolutely will not have further delays and hope that our readers can forgive us.

本社啟示

承印本報之大新印刷公司、因急於添裝新機、故於本期出版後,鬚暫停刊一期。絕不延滯。望讀者原諒。[13]

A second notice explains that new long-running cartoon strip by Huang Wennong was originally intended to be serialized in this issue, but that they were unable to get the printer set up in time, so it would have be delayed until the next issue.[14] Access to quality printing presses would continue to be a problem for the cash-poor members of the Manhua Society going forward into the future, forcing even the most prolific and talented members to supplement their incomes as cartoonists with work in advertising, fashion, and commercial publishing.

Perhaps due to these technical and financial difficulties, by all accounts the first issue of Shanghai Sketch was a commercial flop, and a second issue never appeared. In his autobiography, Ye Qianyu recalls being forced to recoup their losses by selling the entire print run to a paper recycler, and that Wang Dunqing likely provided the majority of the financial capital, since the two other partners were both unemployed.[15] As a schoolteacher, Wang was relatively well off, but would have hardly been in the position to bankroll a periodical with no audience, as evidenced by his publishing the first issue of magazine on credit. Likewise, although about half of the four pages of the broadsheet are taken up by ads for Chinese-produced goods like Dog Head Brand silk stockings 狗頭牌絲襪 and Jade Lion cigarettes 玉獅香煙, it seems unlikely they would have paid much to advertise in a small magazine with an unproven track record. Given their limited funds, therefore, it seems probable that the publisher cut Ye, Wang, and Huang off when the money earned from advertisers and recycling the first issue failed to cover the printing costs.

Dr. Fix-It and the Pioneer Syndicate

On the same day that Ye Qianyu, Wang Dunqing, and Huang Wennong’s venture was launched, a new daily four-panel cartoon strip, Dr. Fix-It改造博士 appeared in the Shenbao, featuring the eponymous Dr. Fix-it, an inventor who makes strange devices to solve everyday problems. Produced by the Pioneer Syndicate 中國第一畫社所制 for the long-running Shenbao supplement Unfettered Talk 自由談edited by Zhou Shoujuan周瘦鵑 (1895-1968), Dr. Fix-It was the brainchild of Ji Xiaobo, and co-written by the famous comic writer Xu Zhuodai徐卓呆 (1881-1958), with illustrations by Lu Shaofei.[16] Although Lu had worked as a freelance cartoonist for the Shenbao throughout the early 1920s, Dr. Fix-It was his first regular feature for the newspaper. Zhang Meisun, another Manhua Society member and veteran Shenbao contributor, and Qin Lifan 秦立凡 (n.d.) were also involved with the project, drawing backgrounds and lettering the speech bubbles, respectively. The following words of explanation were included alongside the first strip of Dr. Fix-It, published January 1, 1928:

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT FROM OUR PAPER

Our office has recently been taking stock of the newspapers of our nation, with an eye to increasing the number of humorous drawings to catch the interest and improve the spirits of our readers. Previously, we provided relatively few drawings of this type. Therefore starting on January 1, Year 17 of the Republic [1928], we will include the humorous drawing of Dr. Fix-It, to be published daily in Casual Chat, a series produced by the Pioneer Picture Syndicate, with all rights retained by this publisher, and all credit owed to them.

本刊特別啟事

本館近鑒吾國報紙, 對於增加閱者興趣及愉快之滑稽畫,尚少提倡。爰自民國十七一月一日起, 採用《改造博士》滑稽畫一種, 逐日刊登自由談, 系中國第一畫社所制, 所權亦系該社所有, 特並聲明。[17]

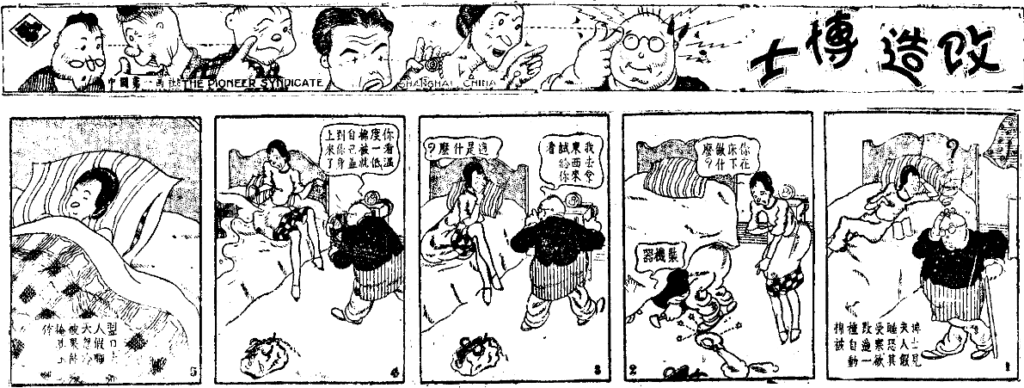

Figure 5.1 The first Dr. Fix-It 改造博士 Shenbao Sunday, January 1, 1928, 26.

According to Lu Shaofei, Ye may have held a grudge against Ji Xiaobo for arranging to have Dr. Fix-It published more than four months earlier than Ye Qianyu’s now famous Mr. Wang 王先生 (See Fig. 4.6), making Dr. Fix-It the first serialized cartoon strip in China.[18] If Ji Xiaobo had approached the unemployed Ye Qianyu, instead of Lu Shaofei, then it is possible that Standard Sizes, or another strip, could have been launched four months earlier on the pages of the Shenbao and taken off there, rather than dying a quiet death on the pages of Shanghai Sketch I. This could explain why Ye Qianyu chooses not to mention Dr. Fix-It in his autobiography. I am somewhat skeptical, however, of Lu Shaofei’s claim that Dr. Fix-It was the first serialized Chinese cartoon strip. As early as 1926, for example, The Young Companion serialized a multi-issue comic strip, The Good Couple 一對好夫妻 credited to Kaixin 開心 [Happy], which was likely a pseudonym for more well-known artist.[19]

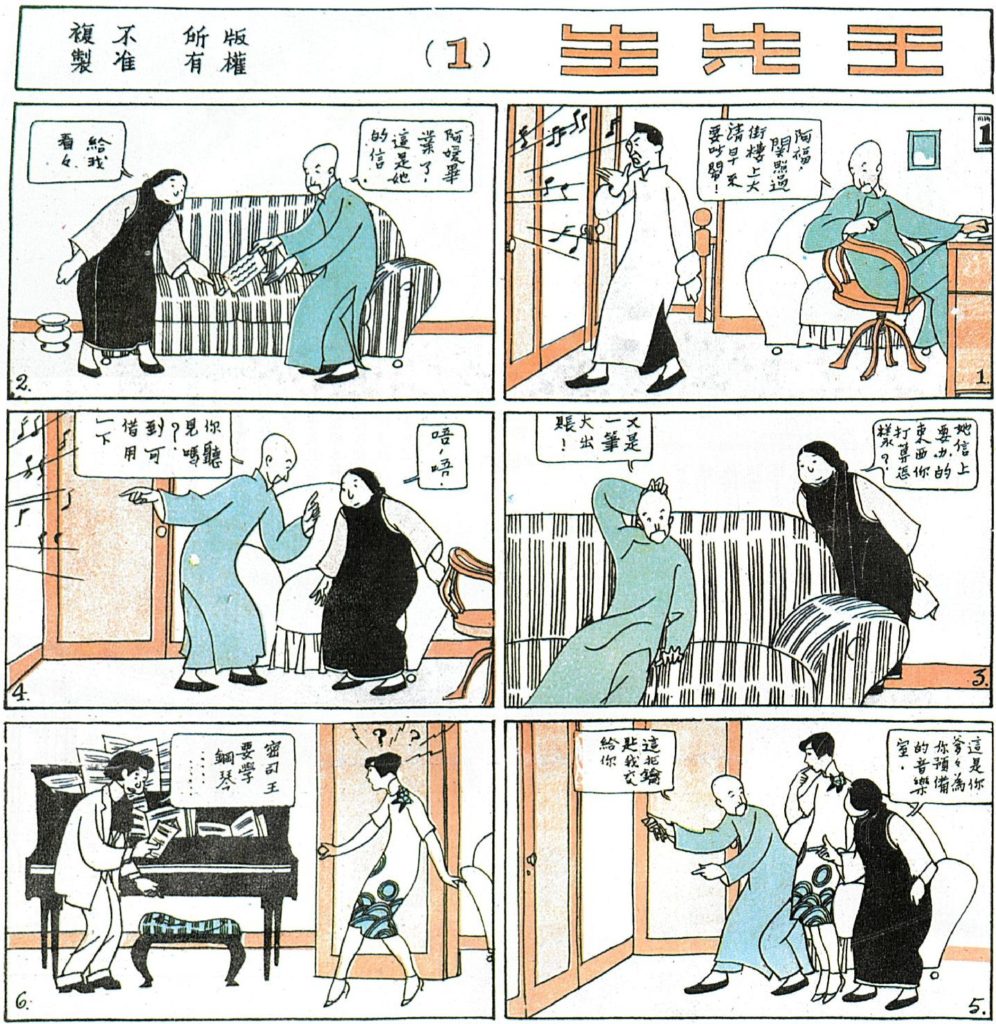

Figure 5.2 The first Mr. Wang 王先生 Shanghai Sketch II, March 21, 1928

Although Ye Qianyu, according to Lu Shaofei, didn’t find out about the cartoon until it had already been published, most of the other members of the Manhua Society were probably aware of the project early on. Aside from fellow Manhua Society members Lu Shaofei, Zhang Meisun, and Ji Xiaobo (the latter two also working in the same office as Ye and Huang Wennong), Xu Zhuodai also likely knew Ding Song and the Zhang brothers. Qin Lifan, meanwhile, had published cartoons by Zhang Guangyu, Huang Wennong and Lu Shaofei in the first issue of Pacific Pictorial太平洋畫報, published four years earlier in 1925.[20] Zhou Shoujuan, meanwhile, had worked closely with Ding Song in the 1910s, drawing a number of memorable covers for Shoujuan’s entertainment magazine The Saturday 禮拜六. To have had a project like this concealed from them, especially when it coincided with their own venture’s failure to launch, would have been hurtful at the very least. Coming at the hands of a colleague and (for Ye) mentor figure like Ji Xiaobo would have made it even worse.

More fundamentally challenging to the group, perhaps, were the ideological differences which existed between the two publications. Whereas the domestic comedy of Dr. Fix-It was clearly meant to be taken as light-hearted entertainment, features such as Wang Dunqing’s essay, “Long Live the Tramp!” in Shanghai Sketch I seems to carry a darker note of subversion beneath the humor.

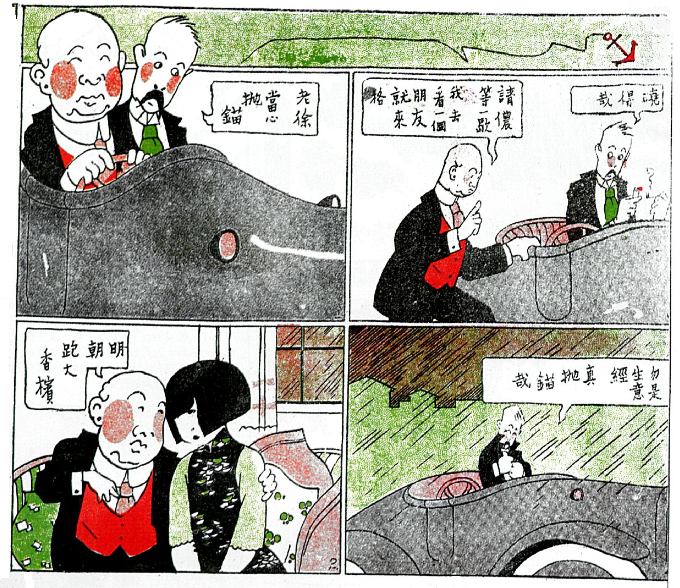

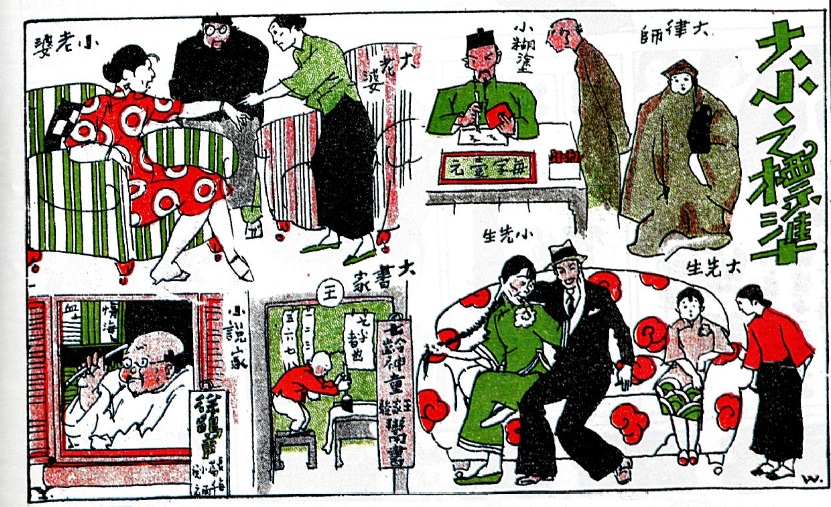

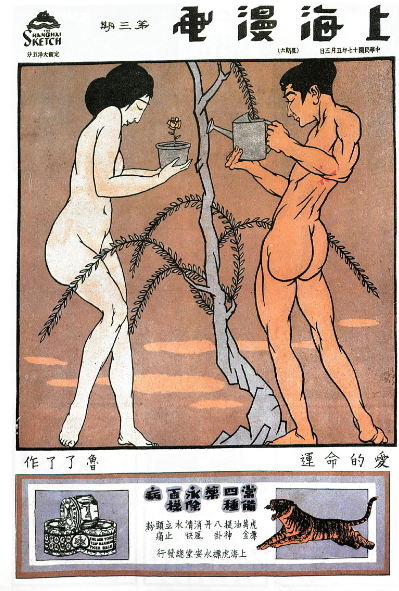

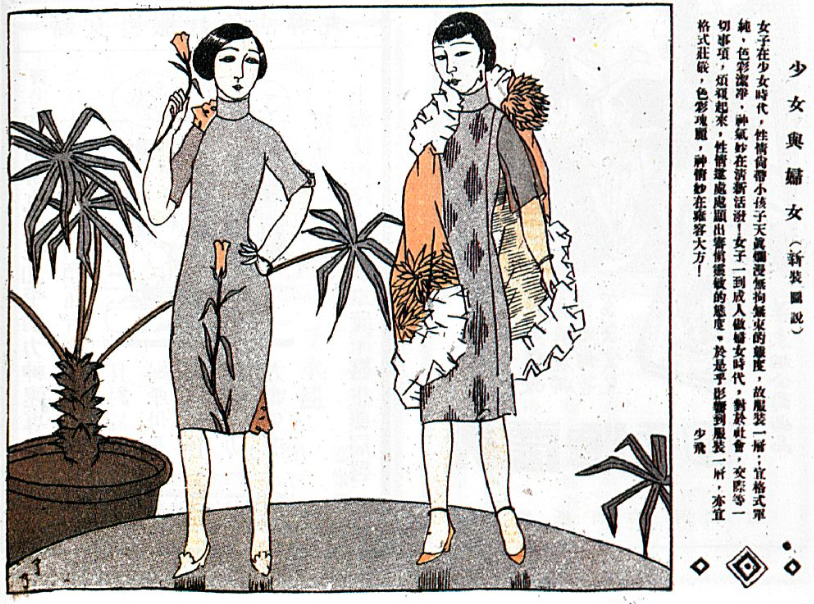

Similarly, cartoons by both Huang Wennong and Ye Qianyu feature overt sexual innuendo: in Huang’s “Jump on the Horse and Drop Anchor,” a man waits in an open top car in the rain for his friend, who is busy romancing his young mistress (See Fig. 4.3); while in Ye’s “Standard Sizes,” a “little wife” (i.e. mistress) is compared to a “big wife” (See Fig. 4.4). This ribald humor is juxtaposed with drawings of attractive women in the latest fashions and even one artistic nude on the back cover, holding a lightbulb in an advertisement for Prosperity Electronics Supply 福來電料行.

Figure 5.3 Huang Wennong “Jump on the Horse and Drop Anchor” 上馬及拋錨 Shanghai Sketch I, January 1, 1928, 3.

Figure 5.4 Ye Qianyu “Standard Sizes” 大小標凖 Shanghai Sketch I, January 1, 1928, 2.

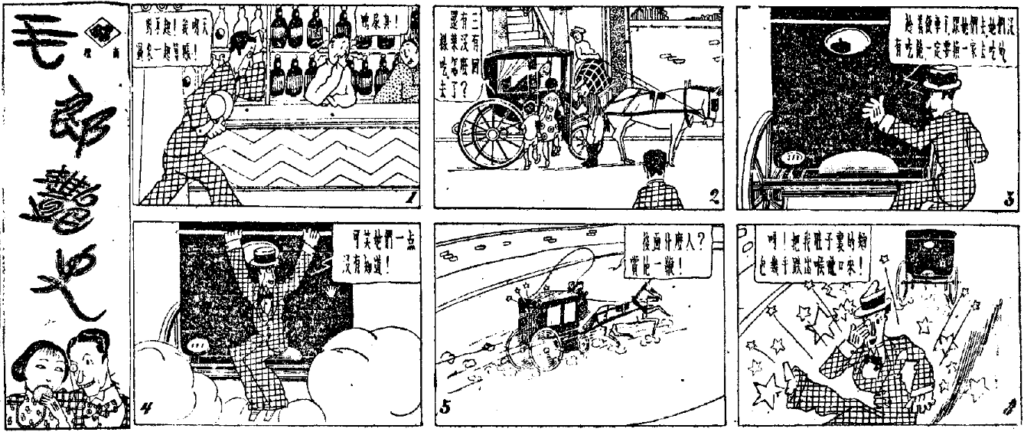

Later that year, almost certainly in response to the relaunch of their competitor, the Pioneer Syndicate launched a second strip, The Romantic Adventures of Mr. Mao 毛郎艷史, dealing with the romantic adventures of a young man in the big city (See Fig. 4.5). Eventually a two more strips were launched: The Traveler 旅行家, an apparent copy of Ye Qianyu’s Mr. Wang, the main character a tall, thin man dressed in a long gown, (See Fig 4.6), and Brother Tao 陶哥兒, starring a naughty child (See Fig. 4.7). This last strip would go to become their most popular after Dr. Fix-It, with both seeing reboots well into the 1930s. The pressure to create new material everyday seems to have pushed the Pioneer Syndicate to their limit, however, because by September, 1928, they were posting notices in Unfettered Talk seeking story ideas for new comic strips.[21]

Figure 5.5 The Romantic Adventures of Mr. Mao 毛郎艷史 Shenbao, June 1, 1928.

Figure 5.6 The Traveler 旅行家 Shenbao, August 8, 1928.

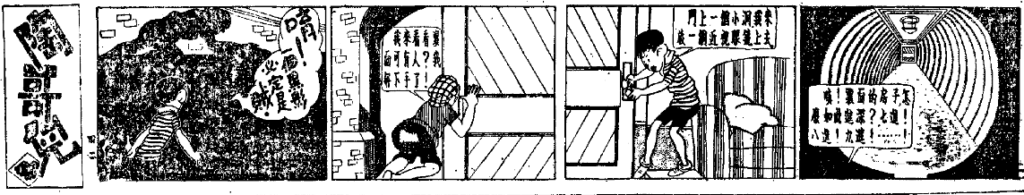

Figure 5.7 Brother Tao 陶哥兒, Shenbao, September 14, 1928.

A long column by Xu Zhuodai followed shortly thereafter, thanking readers for the apparent flood of letters while lamenting that the submissions were, by and large, useless.[22] This notice reveals several important differences between Shanghai Sketch and the Pioneer Syndicate. First, and most obviously, Shanghai Sketch was clearly the more salacious of the two, relying more heavily on sexual innuendo and the female form to entice readers. (Even then, the first installment of Dr. Fix-It takes place in the master bedroom, with Dr. Fix-It installing a temperature sensitive blanket that automatically covers his shapely wife, who wears a short and tight-fitting Western style dress.)

Secondly, Ji Xiaobo and Zhou Shoujian’s Pioneer Syndicate offered no credit to its young artists, Lu Shaofei, Qin Lifan, Zhang Meisun, or even the much older and more well-known Xu Zhuodai. This differed starkly with Shanghai Sketch, which listed the names of its artists and writers not only in notices in the Shenbao, but also throughout the publication itself, giving credit where credit was due. This was not, in fact, an innovation unique to the Shanghai Sketch, however. With the exception of illustrations for children’s magazines and advertisements, most artwork reprinted in magazines and periodicals during the 1920s and earlier gave credit to the artist via his chop or signature, at the very least. The Shenbao went even further, often including the name of the artist and title of the artwork in typeset characters alongside reproduced drawings and paintings, as is the case with Shanghai Sketch. If anything, Pioneer Syndicate was unique in choosing not to give credit.

When combined with the sanitized humor, the choice to not give the artists and writers credit indicates that Ji Xiaobo and Zhou Shoujuan saw manhua not only as tool to boost sales, but also as a new form of entertainment which could be mass produced by a team of faceless artists and writers, “with all rights retained by this publisher, and all credit owed to them.” [23] Given his long tenure at Unfettered Talk and other periodicals before that (where he had worked closely with Ding Song), seems likely that Zhou Shoujuan had learned that when artists and writers became well-known, they could begin to demand higher rates for their work.

It is unclear whether or not Ji Xiaobo was still working at the Songhu Police Station in 1928, although it seems unlikely given that Ye, Huang, and Lu all left or were forced out of their various positions in late 1927. On the other hand, Ji’s joining of the censorship committee of the Department of Education in November, 1929, indicates he maintained close ties with his contacts in the KMT government.[24] Around this same time Dr. Fix-It and the other Pioneer Syndicate strips were cancelled. Despite comments by Jack Chen (relying on information provided by a clearly embittered Wang Dunqing) to the contrary in 1937, however, Ji continued to produce humorous (but apolitical) cartoons well into the 1930s and 40s.[25]

Shanghai Sketch II

In the spring of 1928, not long after the failed launch of Shanghai Sketch I, Zhang Guangyu and Zhang Zhengyu approached Huang, Wang and Ye about joining forces to relaunch their broadsheet as a full-fledged magazine. Taking what they had learned from both China Camera News and The Shanghai Life, the new and improved Shanghai Sketch II would include a mix of fashion, current events, and political commentary. Taking inspiration from Dr. Fix-It perhaps, and also the American comic strip Bringing Up Father, it would also feature a serial cartoon strip by Ye called Mr. Wang 王先生. Named after Wang Dunqing, who Ye claims rejected the title, Shanghainese 上海人, since it had been featured in Shanghai Sketch I, and was therefore unlucky.[26]

In addition to the former Manhua Society members, the new magazine would feature three photographers: Lang Jingshan 郎静山 (1892-1995), an advertising agent for Tiger Balm who would go on to great fame as a photographer; Hu Boxiang 胡伯翔[27] (1896-1989), an artist for British-American Tobacco, where Zhang Guangyu and Ding Song also worked; and Zhang Zhenhou 张珍侯 (? – ?), a successful businessman who worked in import and export.[28] Given Wang’s radical political views, the mundane commercial nature of the new enterprise may have frustrated him, and he probably did not care much for the backgrounds of the three photographers who seem to have mostly been recruited due to their relatively large (at least by looking at their job titles) fiscal resources. Unhappy with the arrangement at Shanghai Sketch II, Wang Dunqing argued with Zhang Zhengyu, leaving after the first meeting of the magazine.

Shortly thereafter the first issue of the new Shanghai Sketch II was published on April 21, 1928. Reinvented as a double-sided broadsheet printed on both sides and folded into quarters, it was only 8 pages long including the cover, illustrated by Zhang Guangyu. A modest success, new issues came out weekly thereafter, distributed every Saturday. According to Ye, Zhang gave him a position as assistant editor on the magazine, which was produced in the back room of an old church in Majiajuan 麥家圈, near the intersection of Fuzhou Road and Shandong Road.[29] Located just north of the walled Chinese city centered around Yu Garden 豫園 and the City God Temple, where Lu Shaofei’s father plied his trade as a portraitist, Foochow Road was one of the most notorious thoroughfares in the International Settlement, with a large number of restaurants, teahouses, and theatres; it “was also traditionally home to bookstores (including the three biggest and most famous: Zhonghua, World, and Great East), whorehouses, and opium dens, as well as being home to the American Club, built in 1924 in American Georgian colonial style with bricks imported all the way from America.”[30]

The very second issue of Shanghai Sketch features a cover by Lu Shaofei, working under the (rather transparent) pseudonym, Lu Liaoliao 魯了了 (See Fig. 4.9). Lu would continue to be a regular contributor to the magazine throughout 1928, providing numerous drawings of fashionable women. Perhaps due to contractual obligations with the Pioneer Syndicate, or perhaps because of the sexually explicit nature of some of the work published under that name, he continued to use his pseudonym until June, with occasional cartoons under his name appearing in Shanghai Sketch II as early as the third issue.[31]

Figure 5.8 Lu Liaoliao [aka Lu Shaofei] “The Destiny of Love” 愛的命運 Shanghai Sketch II, Issue #3, May 5, 1928.

Figure 5.9 Lu Liaoliao [aka Lu Shaofei] “Young Girl and Married Woman” 少女與婦女 Shanghai Sketch II, May 12, 1928.

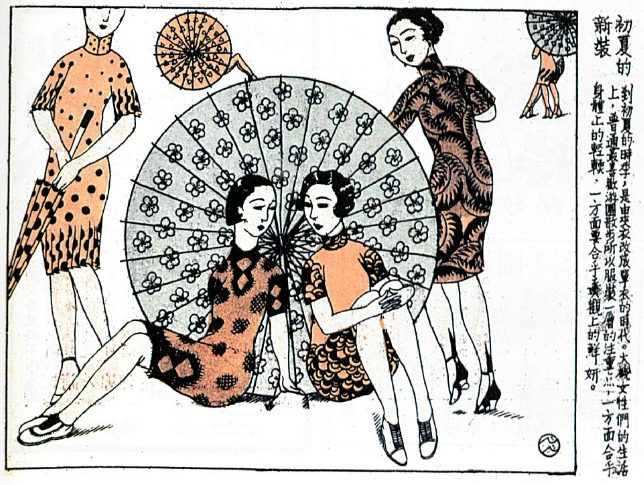

Figure 5.10 Lu Shaofei “New Styles for Early Summer” 初夏的新裝 June 2, 1928.

Shanghai Sketch II is an important publication, not only because it represents one of the first truly successful projects by the members of the Manhua Society, but also because it introduced cartoons to a new generation of artists and writers, in a very real way passing on the torch of the previous generation of cartoonists such as Shen Bochen and Ding Song. Among these artists were artists such as Xuan Wenjie 宣文傑 (1916-1998), who worked as an assistant on Shanghai Sketch II and later publications, and Ding Song’s son, Ding Cong 丁聰 (1916-2009), who would go on to become a major cartoonist in his own right.[32]

Continued in Chapter 6…

[1] Bi Keguan and Huang Yuanlin, Zhongguo Manhua Shi, 85.

[2] See Chapter 1.

[3] “Shi Xuanchuan Bu Shisi Ci Buwu Huiwu” 市宣傳部十四次部務會務 [14th Meeting of the City Propaganda Department], Shenbao 申報, September 26, 1928, 13.

[4] Ye Qianyu mentions both incidents in his autobiography. See Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 63, 67–68. The obscenity trial was also covered in the media, something which Ye credits as bringing new readers to the magazine. See “Shanghai Manhua Bei Kong” 上海漫畫被控 [Shanghai Sketch Accused], Shenbao 申報, October 5, 1928, 16; “Shanghai Manhua Bei Kong An Panjue Fayuan Xuanpan Wuzui Bufang Jiang Ti Shangsu” 上海漫畫被控案判决 法院宣判無罪 捕房將提上訴 [Shanghai Sketch Accusation Judgement: Court Rules Not Guilty, Concession Police Station to Appeal], 申報, October 17, 1928; Shanghai Manhua An Shangsu Kaishen 上海漫畫案上訴開審 [Appeal Heard for Shanghai Sketch Case], Shenbao 申報, November 16, 1928; “Shanghai Manhua Wuzui Bufang Shangsu Hou zhi Panjue” 上海漫畫無罪 捕房上訴後之判决 [Shanghai Sketch Not Guilty: Followup on the Appeal at the Concession Police Station], Shenbao 申報, November 22, 1928.

[5] In April, 1928, it was announced that he was making the sets for an adaption of Journey to the West, and in May Hu Xuguang was said to be working on a new film for the Great China Lily Film Company 大中華百合公司. See “Juchang Xiaoxi” 劇塲消息 [Theater News], Shenbao 申報, April 2, 1928, 18; “Juchang Xiaoxi” 劇塲消息 [Theater News], Shenbao 申報, May 8, 1928, 25.

[6] “Ge tuanti xiaoxi.”

[7] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 61.

[8] Ibid., 62.

[9] “Xin kan shanghai manhua chuban you qi” 新刊上海漫畫出版有期 [A Date Has Been Set for the New Publication Shanghai Sketch], Shenbao 申報, December 25, 1927, 本埠新聞二 section.

[10] Under his various pennames, Wang Qixu translated major works of socialist literature including Hermynia Zur Mühlen’s 1925 collection Fairy Tales for Workers Children translated into English by Ida Dailes as Meigui Hua 玫瑰花(The Rose-bush), Shanghai Chunye Shudian上海春野書店, 1928; Aino Kallas’ 1924 short story collection The White Ship translated into English by Alexander Matson, with a forward by John Galsworthy, as Dao Chengli Qu 到城裡去 (Into Town), Shanghai Nanqiang Shuju 上海南強書局, 1929; and Jack London’s 1908 novel The Iron Heel (Shanghai Taidong Tushuju 上海泰東圖書局, 1929). Finally, in 1932, he edited Duan Pian Xiaoshuo Nian Xuan短篇小說年選:1931 (Best Short Stories: 1931, Shanghai Nanqiang Shuju上海南強書局).

[11] “Shanghai manhua dingqi chuban” 上海漫畫定期出版 [Shanghai Sketch to Be Published Regularly], Shenbao 申報, December 30, 1927, 本埠新聞二 section.

[12] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 62.

[13] “Ben she qishi yi” 本社啟示 一 [Notice from the Editor (1)], Shanghai Manhua 上海漫畫, January 2, 1928, 2.

[14] “Ben she qishi er” 本社啟示 二 [Notice from the Editor (2)], Shanghai Manhua 上海漫畫, January 2, 1928, 2.

[15] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 62.

[16] Lu Yaodong 陸耀東, Dangbo Sun 孫黨伯, and Tang Dahui 唐達暉, eds., “Ziyou Tan” 自由談 [Unfettered Talk], Zhongguo Xiandai Wenxue Da Cidian 中國現代文學大辭典 (Gaodeng Jiaoyu Chubanshe 高等教育出版社, 1998), 441.

[17] “Ben kan tebie qishi” 本刊特別啟事 [Special Announcement from Our Paper], Shenbao 申報, January 1, 1928.

[18] Bao Limin, “Ye Qianyu yu Lu Shaofei (shang),” 24.

[19] Christopher G. Rea points out that in the mid-1920s Xu Zhuodai co-founded a film company called the “Kaixin Film Company” 開心影片公司, and that first chapter of Lu Xun’s short story The True Story of Ah Q appeared in a column called Happy Talk 開心話. Seeing that Kaixin was then a common pseudonym for writers and cartoonists, it is also possible that Kaixin was a penname for Ji Xiaobo, since it appears that was the sole contributor of manhua to The Young Companion before the appearance of The Good Couple. Although the art style differs substantially from the few works which I have been able to uncover which are credited to Ji, like Dr. Fix-It, The Good Couple centers on the relationship between a husband and his wife.

[20] “Taipingyang Huabao Chuban Yuwen” 太平洋畫報出版預聞 [Pacific Pictorial to Be Published], Shenbao 申報, May 27, 1926, 21.

[21] “Zhongguo di yi hua she qiu tougao” 中國第一畫社徵求投稿 [Pioneer Syndicate Seeks Submissions], Shenbao 申報, September 19, 1928, 21.

[22] Xu Zhuodai 徐卓呆, “Duiyu di yi she tougaozhe shuo ji ju hua” 對於第一畫社投稿者說幾句話 [A Few Words on the Submissions to the Pioneer Syndicate], Shenbao 申報, October 26, 1928.

[23] “Ben kan tebie qishi.”

[24] Mentioned in Bu Wuchen, “Gaoshou manhuajia Ji Xiaobo.” See also “Shi Xuanchuan Bu Shisi Ci Buwu Huiwu.”

[25] See Chen, “China’s Militant Cartoonists” and Bu Wuchen, “Gaoshou manhuajia Ji Xiaobo.”

[26] No such cartoon or column appears in the Shanghai Sketch I, indicating that Ye’s memory may have failed him. Christopher G. Rea points out that Ye also relied a fair amount of Shanghai stereotypes, domestic humor, and stock humor, such as henpecked husbands, in addition to traditional Chinese joke books like the Expanded Treasury of Laughs 笑林廣記. See Christopher G. Rea, “A History of Laughter: Comic Culture in Early Twentieth-Century China” (Columbia University, 2008), 219; Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 64, 111.

[27] In his autobiography, Ye Qianyu misremembers Hu Boxiang as Hu Boxu 胡伯诩. See Chen Xueyong 陳學勇, “Shanghai manhua yu Shanghai Manhua” 上海漫畫會與《上海漫畫》 [Shanghai Manhua and Shanghai Manhua], Zhongguo Lunwen Wang 中國論文網, n.d., http://www.xzbu.com/5/view-4269506.htm (accessed February 24, 2015).

[28] Chen Xuesheng 陳學聖, “Modeng Shanghai de Lang Jingshan” 摩登上海中的郎靜山 [Modern Shanghai’s Lang Jingshan], Zhongguo Meishu Guan 中國美術館, n.d., http://www.namoc.org/xwzx/zt/langjingshan/langjingshan5/langjingshan6/201405/t20140507_276688.htm (accessed September 12, 2015).

[29] In his autobiography, Ye Qianyu misremembers the name of the area as Maijiayuan 麥加園. In fact the, area was named Maijiajuan 麥家圈 after the founder of the London Missionary Society Press 墨海書館, English protestant missionary Walter Henry Medhurst, whose Chinese name was Maidousi 麥都思. Mai 麥 refers to Medhurst, jia 家, meaning ‘family,’ acts as a possessive particle, and juan 圈 means ‘sty’ or ‘pen,’ apparently referring to the fact that Medhurst’s first press was powered by an ox. See Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 63; Zhang Zonghai 張宗海, “You Mohai Shuguan Er Xing de Lao Jie – Maijiajuan” 由墨海書館而興的老街——麥家圈 [An Old Street That Began with the London Missionary Society Press – Maijiajuan], 上海市地方志辦公室, n.d., http://www.shtong.gov.cn/node2/node71994/node71995/node72000/node72014/userobject1ai77393.html (accessed September 18, 2015); Zhang Xiantao, The Origins of the Modern Chinese Press: The Influence of the Protestant Missionary Press in Late Qing China (Routledge, 2007), 106–8.

[30] French, The Old Shanghai A-Z, 108.

[31] Given that at least one notice in the Shenbao lists Lu Liaoliao and Lu Shaofei as separate artists, it seems more probable that Lu was more concerned about hurting his reputation than he was about offending Ji Xiaobo or Zhou Shoujuan. See “Chubanjie Xiaoxi” 出版界消息 [News in the World of Publishing], Shenbao 申報, April 30, 1928, 19.

[32] Ye Qianyu mentions working with Xuan Wenjie in his autobiography, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 65.