This is first chapter in my MA thesis completed in December 2015 at the Department of Asian Studies at UBC, The Shanghai Manhua Society: A History of Early Chinese Cartoonists, 1918-1938. Since passing my defense, I’ve decided to put the whole thing up online so that my research will be available to the rest of the world. I’ve also decided to use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can share it with anyone you like, as long as you don’t charge money for it. Over the next couple of days I’ll be putting up the whole thing, chapter by chapter. You can also download a PDF version here.

Fittingly, given the role free trade agreements have played in the development of 21st century cities, Shanghai of the early 20th century, “portent of the modern world,” was made possible by the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 which designated Shanghai a ‘treaty port,’ becoming a casualty of the first Opium War between the rapidly expanding British Empire and the ailing Qing Empire.[1] The Manchus had ruled China since overthrowing the ethnic Han Ming dynasty in 1644, overseeing a huge growth in population and territory. According to many scholars who have studied the era however, the Manchu reforms were primarily targeted at restoring rather than reforming political, economic, or social institutions which they inherited.[2] Eventually, foreign aggression forced the imperial government to begin efforts toward Western-style modernization.[3] The British treaty was soon followed by similar French and American treaties in 1844. Chinese entrepreneurs flocked to the foreign concessions to take advantage of the new economic opportunities they provided, while many others sought refuge from the political turmoil of the Taiping Rebellion of 1851 to 1864. Foreign products, most famously opium, but also English wool, Indian cotton, Russian furs, American ginseng, and silver bullion mined in Mexico were imported into China through the docks and godowns [warehouses] of the Huangpu, and while goods such as tea, silk, and porcelain were exported from the farms and villages of the Chinese countryside. Over time, a local manufacturing industry (of which printing presses were to form a large part) emerged, eventually overtaking the import-export business.

In 1895, the defeat of the Qing in the first Sino-Japanese War led to the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which created the first Japanese concessions in China while also establishing a legal precedent for foreign-owned manufacturers within China. At first, Chinese industrialists struggled to compete with the capital resources and more advanced manufacturing techniques of foreign-owned factories. Chinese firms quickly latched onto the idea of using the rhetoric of nationalism to sell their products, which often came at a higher or equivalent real cost, with a lower level of perceived quality. Anti-Japanese sentiment was stoked even further by the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, when Japan seized additional concessions in the Liaodong peninsula 遼東半島, in the northeastern province of Liaoning 遼寧, which at the time was known as Fengtian 奉天.

When the by then widely despised Qing government was finally overthrown in late 1911, the ensuing wave of nationalism help bring by Sun Yat-sen’s 孫中山 (1866-1925) Kuomintang 國民黨[Chinese Nationalist Party, KMT] to power, with the support of the leading Qing general, Yuan Shikai 袁世凱 (1859-1916) and his modernized Beiyang Army. Meanwhile, business owners quickly realized the opportunity to seize market share from foreign imports with the establishment of the Chinese National Product Preservation Association 中華國貨維持會. Beyond simply promoting Chinese products, the CNPPA would go to organize numerous anti-Japanese boycotts from its headquarters in Shanghai, which were largely suppressed by the Republican government under pressure from the Japanese legation.[4]

When World War I broke out in August, 1914, Japan, which had been formally allied with England since the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance, seized the German concession in Qingdao, Shandong province and proceeded to force the Yuan Shikai’s government, which had ejected Sun Yat-sen’s KMT the previous year, to accept a list of demands, including the recognition of the various Japanese territorial claims in China. In late 1915, Yuan reinstated the monarchy, declaring himself Emperor Hongxian of the Chinese Empire 中華帝國大皇帝洪宪, a controversial decision which led to the break-up of his government even before his death from kidney failure in 1916.

Following Yuan’s death, the Beiyang Army split into warring factions, which coalesced into three main groups: the Anhui clique 皖系, the Zhili clique直系, and the Fengtian clique 奉系.[5] At first, the most powerful of these was the Anhui clique, which controlled Beijing under the leadership of Duan Qirui 段祺瑞 (1865-1936), an Anhui native, with the support of the Japanese who provided loans in exchange for under-the-table territorial concessions. For similar reasons, the Japanese also supported the Fengtian clique, which was based in the far northeastern corner of the country above Korea, known as Manchuria, and led by Zhang Zuolin 張作霖 (1875-1928), with the support of Zhang Zongchang 張宗昌 (1881-1932) and others. Hebei and its surroundings, meanwhile, were controlled by the Zhili clique, led by Cao Kun 曹錕 (1862-1938), in partnership with Wu Peifu 吳佩孚 (1874-1939), Feng Yuxiang 馮玉祥 (1882-1948), and Sun Chuanfang 孫傳芳 (1885-1935).

For much of the late 1910s and early 1920s, however, the province of Canton in the far south was largely controlled by the KMT under Sun Yat-sen’s leadership. Sun initially formed alliances with local warlords, in particular Chen Jiongming 陳炯明 (1878-1933), but found them to be unreliable allies in his quest to reunify China under KMT rule. In 1924, Sun founded the Whampoa Military Academy 黃埔軍校 in Canton with support of the Soviet Union and the New Guangxi Clique 新桂系, which controlled neighboring Guangxi province, a major center of opium production.[6] As part of the terms of support from the Bolsheviks, the KMT had formed an alliance with the Chinese Communist Party in 1923, known today as the First United Front of the Nationalists and Communists. In 1925, Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 (1887-1975), commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy, drew on the graduates of Whampoa to found the National Revolutionary Army (NRA), a force which would ultimately retake the country for the KMT following Sun Yat-sen’s death in 1925.

In was during these turbulent times that Ye Qianyu, today the most well-known member of the Manhua Society, grew up. Ye’s early life story is unique among his peers not so much in the particulars, but because we know a great deal about it, largely thanks to his autobiography which was published in the 1990s. Ye’s early life illustrates how the numerous military conflicts of the late 1910s and early 1920s shaped the lives and aspirations of the first generation of manhua artists in China.

Ye Qianyu: The Student

Born in 1907 into a family of merchants in Tonglu county 桐廬縣, Zhejiang province, in the mountains to the southwest of Hangzhou at the confluence of the Fenshui and the Fuchun, at age seven Ye entered Baohua Primary School 葆華小學. After graduating in 1916 he enrolled at Zixiaoguan Advanced Primary 紫霄觀高等小學 where in addition to his other coursework he also studied traditional ink painting and handicrafts. He spent five years at Zixiaoguan before graduating in 1921.[7]

While Ye was in his third year Zixiaoguan, World War I ended with the Treaty of Versailles. Signed on June 28, 1919, due to secret territorial concessions granted by the various warlord cliques in exchange for loans and military equipment, this controversial document upheld Japanese claims over Qingdao and the Liaodong peninsula, despite China having contributed some 140,000 laborers to the Allied war effort. More than 800 miles to the north of Hangzhou, student protests against both the warlords and Japan took place in the capital of Beijing on May 4, 1919, quickly spreading to rest of the country. The “May Fourth” movement, as it came to be known, was a watershed moment for a new generation of Chinese intellectuals who increasingly came to advocate for the abandoning of “backward” Chinese tradition in favor of the modern ideals of “science and democracy.” Although he was only 12 when the May Fourth movement began, in his memoirs Ye recalls participating in student protests inspired by the May Fourth movement several years later while going to school in Hangzhou.

1n 1920, Ye applied to the Zhejiang Provincial Number One Teaching Training School 浙江省立第一師範學校, a famous public school in Hangzhou, but failed the entrance exam. The next year he applied a second time to the same school, in addition to two more schools, Hangzhou Number One Middle School 杭州第一中學 and the more recently established Hangzhou Salt Works Middle School 杭州鹽務中學. Although he failed the entrance exam to Zhengjiang Number One a second time, Ye tested into both of the other schools.

Despite wanting to attend Hangzhou Number One Middle School, in the end Ye decided to attend the Salt Works Middle School, apparently under pressure from his father. Although the other school would have given him the option of going on to university after graduation (and also would have had art classes), Salt Works Middle School had been established to train future employees in the government salt monopoly. For Ye’s father, whose business was struggling at the time, it likely seemed to be a better investment than the more nebulous promises of a well-rounded education. Tasked with providing war reparations to the Eight-Nations Alliance following the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901, the salt monopoly faced a shortage of staff fluent in foreign languages to deal with the representatives of the Eight-Nations Alliance. In light of his involvement in the May 4 Movement, Ye, was understandably less enamored with this career path.

Along with his girlfriend, Wang Wenying 王文英, and three other classmates, Ye ran away from school in the summer of 1924, taking a passenger ferry to Xiamen where they attempted to gain early admittance to Xiamen University 廈門大學. Only one of the five friends managed to pass the exam, but the other four, including Ye and Wang, were allowed to stay on at the preparatory school for Xiamen University. They soon found themselves trapped in Xiamen, however, due to the outbreak of the Jiangsu-Zhejiang War 江浙戰爭 in September, 1924.

Following the Zhili-Anhui War of 1920, when Duan Qirui’s Anhui clique had been defeated by Cao Kun and Wu Peifu’s Zhili clique, former Anhui clique generals, Yu Longxiang 盧永祥 (1867-1933) and Qi Xieyuan 齊燮元 (1885-1946), who had sworn allegiance to the Zhili clique, continued to be rule over the provinces of Jiangsu (containing Shanghai), Anhui, and Zhejiang (containing Hangzhou). For the next two years, meanwhile, Beijing found itself nominally under the joint rule of the Zhili and Fengtian cliques. This partnership fell apart in 1922, with the advent of the First Zhili-Fengtian War, which saw the Fengtian Army routed, forcing Zhang Zuolin to retreat to Manchuria. The Jiangsu-Zhejiang War of 1924 which trapped Ye Qianyu and his friends in Xiamen began as a struggle between Lu and Qi for control of the Chinese districts of Shanghai, and quickly escalated into the Second Zhili-Fengtian War, for which Zhang had been enthusiastically preparing since his embarrassing defeat only two years earlier.[8]

To help overthrow Qi, Lu had partnered with He Fenglin 何豐林 (1873-1935), the Military Defense Commissioner of Shanghai, and Du Yuesheng 杜月笙 (1888-1951), a powerful crime boss in the Green Gang 青幫, which controlled the opium trade in Shanghai. With the Zhili clique’s northern reserves forces tied up in skirmishes with the Fengtian Army, Sun Chuanfang 孫傳芳 (1885-1935), also of the Zhili clique, decided to step in to support Qi Xieyuan, leading his forces up from Fujian, where he had been stationed by Cao Kun and Wu Peifu in early 1923.

By October, 1924, only one month after the Jiangsu-Zhejiang War had begun, it was already over. Sun Chuanfang and Qi Xieyuan had defeated Lu Yongxiong, who fled to Japan, with Sun replacing Lu as the military governor of Zhejiang. In response, the victorious Fengtian clique attempted to extend their influence into the Yangtze River delta region, with Zhang Zuolin sending Zhang Zongchang and Feng Yuxiang’s Guominjun國民軍 [National Army] on the Anhui-Fengtian expedition to take the Chinese districts of Shanghai from Qi Xieyuan. After being quickly defeated in April, 1925, Qi Xieyuan was forced to flee to safety in Japan, and the Guominjun occupied the Chinese parts of the city. By the fall, however, Zhang Zongchang had been recalled to Shandong, allowing Sun Chuanfang to ultimately take control of Jiangsu, Anhui, and Jiangxi over the next three years, becoming one of the most powerful men in China. Ye Qianyu, meanwhile, was forced to stay in Xiamen for another five months, not having enough money to return home. While Ye was off trying to make a name for himself, the Ye family store had gone bankrupt, which meant that the family had been reduced to living off the income they received from renting out their property.

Failing to gain admission to Xiamen University, in March of 1925, Ye was convinced to return home when his father took out a 100 yuan mortgage on their family property to bring his son back from Xiamen. Back in Tonglu, Ye’s father pleaded with him to return to the Hangzhou Salt Works Middle School to finish his degree. Ye resisted, and after running away and threatening to kill himself, he was able to convince his father to let him apply for an apprenticeship as a clerk in the retail department of the Three Friends Co. textile factory 三友商業社.[9] One of the largest and most well-known Chinese-owned companies at the time, Three Friends Co. had been posting wanted ads in the Shenbao 申報, a prominent Shanghai newspaper with distribution throughout China. Founded by the English entrepreneur Ernest Major (1841-1908), the Shenbao was a pioneering Chinese language newspaper which played a key role in the development of the public sphere in Shanghai from when it was founded 1872 to when it finally shut its doors in 1949. It is not surprising, then, that it also played a critical role in the development of Chinese cartooning, launching the first illustrated magazine in China, the Dianshizhai Pictorial 點石齋畫報, and providing employment to many of China’s first cartoonists, from Shen Bochen and Ding Song, to Lu Shaofei and Huang Wennong.[10]

After passing an interview with Wang Shuyang 王叔暘 (1903-1973) in the office of Three Friends Co. by demonstrating his drawing ability, Ye was hired as apprentice clerk selling cloth in the Three Friends department store on Nanjing Road, the bustling commercial thoroughfare of the British-American International Settlement (See Fig. 1.1).[11] Located on the northwest bank of the Huangpu River, which runs diagonally through the Yangzte River Delta, the International Settlement was sandwiched between the long rectangle of the French Concession and the Chinese walled city, containing Yu Garden 豫園 and the City God Temple 城隍廟, to the south, and Suzhou Creek 蘇州河to the north. This rough stretch of water, thick with effluents of the many tanners and dyers located along its banks, marked the border to the Chinese controlled district of Zhabei, with the terminus of the Nanjing-Shanghai Railroad and a large number of factories, including those of Three Friends Co.

Figure 1.1 Three Friends Co. storefront on Nanjing Road, date unknown.[12]

Named after the former imperial capital of China, in Chinese it was often referred to as Main Road 大馬路, Nanjing Road ran east to west from the waterfront, known as the Bund, to the Shanghai Race Course (since razed by the communists and replaced with appropriately named People’s Park). For a young man from a small town in the Zhejiang hills like Ye, Nanjing Road was a heady place,

a major economic artery, a mix of East and West, where the gathered multitudes of living, breathing things all started to affect my way of looking at things. I went from seeing things with the eyes of a peasant from the local county seat, to seeing things with the eyes of a Shanghaiese. My brain became filled with new and exciting things, seeing the changes in society; spending time on Nanjing Road, full of art and culture, I became aware of the things which I loved, the things which I needed, and so I made a choice, then and there. This is probably why I gradually realized that I needed to change jobs, to spend time improving and absorbing and digesting these things.

一條經濟大動脈,華洋雜處,會公眾生,把我這帶點農民意識的小縣城的眼睛,逐漸變成十裏洋場的眼睛,腦子裏也裝滿新鮮事物和社會新面貌;又接觸了布滿南京路的文化藝術環境,使我對所愛的所需的有所認識,進而有所選擇。也許就是這個原因,我逐漸意識到需要換一個工作環境,來充實和消化這些東西。

Soon thereafter Ye was promoted to the advertising department of Three Friends Co. where he met Ji Xiaobo, a twenty-five year old artist from Jiangsu who would provide a model of success for the ambitious Ye. Although largely forgotten today, Ji Xiaobo’s somewhat fraught relationship with Ye helps explain the likewise fraught formation of the Manhua Society.

Ji Xiaobo: The Master

Born in 1901 in Xinzhuang Village 新庄鄉, Changshu county 常熱縣, Jiangsu江蘇省, just south of the Yangtze River, in Ye Qianyu’s words, Ji “…had received a formal art education in Shanghai, and so he was familiar with foreign music. He told us that the Municipal Concert Hall had free seats on the third floor, open to the public, and that he could take us to check it out if we were interested” 在上海受过正规美术教育,接触过外国音乐, 他告诉我们,市政厅音乐堂的三楼,有免费的座位,可以自由出入,你们有兴趣,可以带你们去见识见识.[13] At first Ye was unimpressed with the stiff formality of the classical orchestra, finding that it compared unfavorably with the spontaneity and liveliness of the folk music he had heard in amusement parks while growing up in the Zhejiang countryside, and one can easily imagine the older and more erudite Xiao lecturing the younger and more impetuous Ye about the fine points of Western music. Yet after repeated trips to the Municipal Concert Hall Ye recalls that he found himself gradually beginning to enjoy it.

Ye also recalls that Ji Xiaobo was responsible for finding a new dormitory to rent when the company outgrew the cramped quarters they had been living in. When they moved into the new dorm, Ji used his own money to buy a gramophone. After long hours at Three Friends, the interns would crowd around the turntable to listen to Peking opera recordings and take turns singing stanzas from their favorite performances. Ji’s generosity rekindled a childhood fascination with the theatre which was to last for rest of Ye’s life.

Ji Xiaobo’s own career had begun nearly seven years earlier, in the summer of 1918, when Ji and his friend, Fan Zhixi 範志希 (n.d) were hired by the artist and entrepreneur Sun Xueni孫雪泥 (1888-1965) to edit his Shanghai Resident News 上海市民報. Sun Xueni had originally been employed as an art editor at The New World Daily 新世界日報, published by the New World Entertainment Hall新世界游樂場, before setting up his own press, Shengsheng Fine Arts Company 生生美術公司 a newspaper publisher which doubled as an advertising agency, producing illustrated ads for other newspapers. [14] Seventeen years old and just out of high school, Ji Xiaobo made fast friends with the eighteen year old Zhang Guangyu, who at the time was apprenticed to Ding Song (1891-1972), the editor of World Pictorial 世界畫報, a second publication also printed by Shengsheng.[15] Less than ten years later, the three would collaborate with Ye Qianyu, among others, to form the Manhua Society.

In the fall of 1919, Ji Xiaobo joined the first class of the Shanghai Teacher Training College of Art 上海藝術專科師範學校 which had just been established by two graduates of Zhejiang Provincial Number One Teacher Training School (the same school Ye Qianyu had failed the entrance exam to twice), the artist Wu Mengfei吳夢非, Liu Zhiping劉質平, who had also studied music in Japan. It is somewhat surprising that Ji would choose to enroll at this school, given that at the time Ding Song was a teacher and provost at the more established Shanghai Art Academy 上海美術院 . Perhaps cost was a concern, since tuition was almost certainly cheaper at the Teacher Training College of Art, which didn’t even make enough money to employ its teachers full time.[16]

Whatever the reason, Ji Xiaobo’s decision would turn out to be a fortuitous one when Wu Mengfei and Liu Zhiping convinced their former classmate Feng Zikai豐子愷 (1898-1975) to join the school. Although Feng Zikai would later become a famous cartoonist, at the time he was still struggling to develop the unique fusion of traditional Chinese painting and Western cartooning for which he would become known. Feng Zikai and his publisher, Zheng Zhenduo鄭振鐸 (1898-1958) decided to call his iconoclastic cartoons manga 漫畫 [casual pictures], borrowing the Japanese term for cartoons and comics which Feng had picked up while studying in Tokyo. [17] The term, pronounced manhua in Mandarin, was quickly adopted by other Chinese cartoonists, in particular the future members of the Manhua Society, who were likely looking to replace the terms huajihua滑稽畫 [humorous drawings] or fengcihua 諷刺畫 [satirical drawings] while also suggesting an association with the drawings of Feng, which had become wildly popular following the publication of Feng Zikai’s Manhua子愷漫畫 in Literature Weekly文學週報 in May, 1925.[18]

Because he does not seem to have contributed to Shanghai Sketch I or II in comparison to the other members of the Manhua Society, Ji Xiaobo is not particularly well-known for his cartoons today. He also does not seem to have be a very prolific artist. This may of course be because his advertising work for the Three Friends Co. is, of course, uncredited. It is also possible that he published under a penname for professional reasons, or that he was simply too busy with his work to spend much time making cartoons.

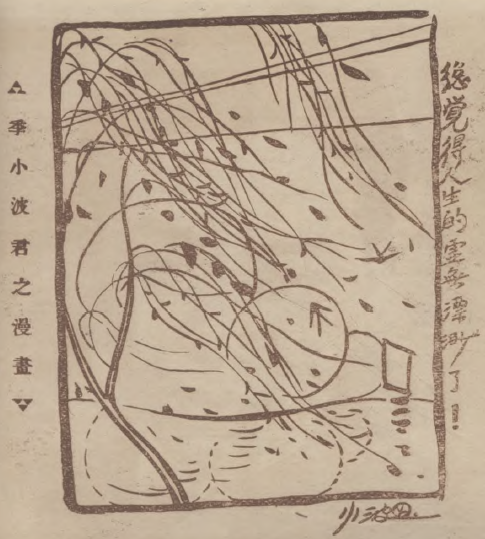

Although earlier works likely exist, the earliest manhua by Ji that I have been able to uncover was published in The Young Companion in early 1926, over a year before he joined the Manhua Society. It depicts the swaying branches of a willow tree blowing in the wind, with what appears to be a junk on the water in the distance. The full moon lies just above the horizon line, reflected dimly in the water, while two swallows flit among the branches, barely distinguishable from the drifting leaves. In constrast with the thick, organic brushstrokes Ji has used to create the scene, three thin, straight lines intersect the top of the image, suggesting perhaps powerlines, or the beam of a pavillion. Beside his drawing, Ji has written, “I always feel that life is so unreal!” 總覺得人生的虛無縹緲了!

Figure 1.2 Ji Xiaobo “I always feel that life is so unreal!” 總覺得人生的虛無縹緲了!The Young Companion, Issue 1, February 15, 1926, 21.

Apparently the image (clearly showing a strong debt of influence to the work of Feng Zikai) was well received by readers, because the next month two more manhua by Ji Xiaobo were published in the same magazine the next month. Both depict nude women striking defiant poses, drawn in a style similar to his first drawing. The first is titled “Warrior” 戰士, and shows a woman in profile, her right arm raised to sky holding a sword with a thin blade and ornate guard, probably a fencing foil. Her chin is raised upwards, and her long, light colored hair falls behind her almost touching the ground. A tall conifer stands in the background before an enormous full moon, duplicated three times, which fills half the page. In the second image, titled “Fullness” 圓滿, the woman has medium length jet black hair, but like the first woman, her chin points straight up into the air. Both arms are raised to the sky, framing two swallows. As with the previous two images, a full moon floats in the sky.[19]

Figure 1.3 Ji Xiaobo “Warrior” 戰士 The Young Companion, Issue II, March 15, 1926.

|

Figure 1.4 Ji Xiaobo “Fullness” 圓滿 The Young Companion, Issue 1I, March 15, 1926.

|

Ji’s time with Feng Zikai was brief, because in late 1920 or early 1921, the Shanghai Resident News fell afoul of a group of criminals (possibly Du Yuesheng’s Green Gang) forcing Ji to abandon his studies and leave Shanghai. Feng Zikai, meanwhile, left Shanghai in the spring of 1921 to study abroad in Japan. Thanks to Fan Zhixi, Ji was able to find a job at Zhengda Daily 正大日報a newspaper in Suzhou, edited by Sun Yiwen孫一文 (n.d.) under the management of Zhu Xiliang 朱錫梁 (1873-1932).[20] Zhu Xilang was former member of the Tongmenghui 同盟會, Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary organization which had help overthrow the Qing empire to establish the KMT and the Republic of China. It is not surprising, then, that he was deeply critical of the local warlord government which had usurped power from the militarily weak KMT.[21] This paper was also shut down, this time by military police, forcing Ji to return to his hometown to evade arrest. While in his hometown, Ji got in trouble again by trying to organize a land reform movement, leading him to sneak back into Shanghai in early 1924,[22] where he found a job editing the Three Friends Co. promotional periodical The Light of the Triangle 三角之光.[23] Never one to forget a debt, Ji used his influence at Three Friends to publish new cartoons by Feng Zikai, who had by then returned to China and begun creating works in a new style heavily influenced by the casual sketches of the Japanese artist Takehisa Yumeji竹久夢二 (1884-1934), in addition to two Chinese artists who created works of similar a style, Chen Shizeng陳師曾(1876-1923) and Zeng Yandong (1750-1825) .[24]

It may seem curious that Feng Zikai never joined the Manhua Society, given his early passion for cartooning. He was least casually acquainted with Ji Xiaobo, and he likely knew other members of the group as well, particularly Ding Song and Wang Dunqing. The simple answer is that Feng Zikai operated in different social circles from the members of the Manhua Society, who were mostly self-taught, and employed in varying capacities in publishing and teaching. The tradition of literati painting, whose ingrained hierarchy and culture of connoisseurship has largely been duplicated by Chinese proponents of Western art, has welcomed Feng’s works in a way that members of the Manhua Society could never hope for. As Feng Zikai’s biographer, Geremie Barmé argues,

By monopolizing the word manhua, along with all of its modern Japanese and commercial cultural associations, the members of the [Manhua Society] marked themselves off from an art scene that had no place for them, while occupying a viable niche in the commercial art and magazine market, which fed on sensationalism and topicality. In so doing, they also eclipsed the lineage of the manga as a term for describing Feng Zikai’s equally unorthodox work.” [25]

More importantly, perhaps, Feng had different goals from the members of the Manhua Society, who saw their purpose to either entertain (through either humor or titillation) or to convince (via political satire or outright propaganda). Feng, on the other hand, seems to have wanted his cartoons to enlighten his readers, to inspire stillness and reflection in an age of turmoil.

Humorous manhua were not the only type of cartoon artwork to emerge in China during the first half of the 20th century. For example, a form of comics, closer in style to Western superhero comic books and pulp fiction, lianhuantuhua 連環圖畫 , or ‘linked picture books,’ also known as lianhuanhua 連環畫and xiaoren shu 小人書 [kid’s books], were extremely popular 1920s as a form of cheap entertainment which could be rented on the street corners of Shanghai and other cities across China.[26] Unlike the Manhua Society, however, early authors of lianhuantuhua were not feted by social critics and so left little behind to posterity, with most examples of surviving works dating from the post-1949 period, when the Chinese Communist Party began to promote illustrated stories as propaganda for the illiterate masses in the countryside.[27]

Likewise, other art forms related to the cartoon, such art deco, cubism, and Latin American-influenced portraiture all gained currency in Shanghai at this time, alongside manhua and lianhuantuhua. It not surprising then, that in his study of the aesthetic influences of manhua periodicals, Paul Bevan finds that elements of both art deco and cubism, in addition to art nouveau, surrealism, symbolism, and the English arts and crafts and decadent movements can be seen in the publications of the Manhua Society members from the late 1920s.[28]

Burnt Bridges and Bad Blood?

Ye Qianyu left Three Friends after one year, in 1926, and at first glance he does not seem to have had any hard feelings towards his former employer. In his autobiography he mentions that he can’t remember a specific reason for leaving, other than a general feeling that he wouldn’t have as many opportunities to develop his artistic abilities there as he had hoped for. Fortunately Ye was able to find a job at Central Plains Publishing House 中原書局 in Shanghai with the help of an unnamed friend, where he was tasked with illustrating textbooks. After working at the publishing house for a while, a former coworker from Three Friends (also unnamed) asked Ye to paint the backdrop for a theatre in his hometown of Changshu County. Ji Xiaobo is from Changshu County, so it seems highly likely that the former coworker was Ji. It seems curious, though, that he chooses not to name his benefactor, and could potentially indicate that Ji and Ye had some sort of falling out before or after he left his job at Three Friends, or that Ye felt that he should downplay his close relationship with Ji.

Indeed, throughout his autobiography, Ye Qianyu impolitely refers to Ji Xiaobo as “that guy named Ji,” 那位性季的 rather than his full name, which he uses only once, when he passingly refers to him as “my old coworker from Three Friends, Ji Xiaobo” 三友社的老同事季小波. This is hardly the way one would expect Ye to refer to the man who helped him begin his career in publishing, and suggests the possibility of bad blood between the two cartoonists. The answer may lie in Ji Xiaobo’s political affiliations, which may have led Ye to burn his bridges with his former colleague after the founding of the PRC.

In a 1938 article on Chinese cartoonists, left-wing journalist and cartoonist Jack Chen mentions that one of the founding members of the Manhua Society “joined the government and secured a job that kept him from doing embarrassing cartoons.” While Chen fails to elaborate on what exactly he meant by embarrassing, from the context is seems that Chen was implying that this individual, whoever he was, felt that drawing cartoons was less dignified than working for the government. Whether this is true or not, Chen may have also been channeling the feelings of his father, Eugene Chen 陳友仁 (1878-1944), a prominent overseas Chinese lawyer who served as a foreign affairs advisor and diplomat for Sun Yat-sen and the Nationalists in the 1920s.[29]

Although Lu Shaofei went on to serve as a KMT official in Lanzhou during the war, acting as the director of the Lanzhou Municipal Social Services Department 蘭州市社會服務處 until the defeat of the KMT in 1949, Lu didn’t actually start this job until 1941. Instead, Chen was almost certainly referring to Ji Xiaobo, who worked as a censor of the arts 美術視察 for the KMT-controlled Shanghai Department of Education 海市教育局 from 1929 to 1937. Following the communist takeover in 1949 Ji seems to have been able to successfully claim that he had been working uncover, but it was not until 1981 that he was able to find his way back in publishing, when he was appointed editor of Xuelin Press 學林出版社. According to a newspaper article published in 2002, four years later he was completely rehabilitated and given an unspecified government position, not unlike those Ye Qianyu and Zhang Guangyu and many other cartoonists received directly after the war. [30]

Even if Ji’s small number of published works and affiliation with the KMT might have limited his fame in later years, articles published under the title “Long Lived Manhua Artist Ji Xiaobo” indicate that Ji seems to have enjoyed playing the role of “master” cartoonist, as one of the founding members of the Manhua Society.[31] It also undeniable that Ji Xiaobo did incredibly well for himself, given his humble origins, and that without him, his “student,” Ye, may never have had the opportunity to meet the other members of the Manhua Society and achieve the levels of success he later did.

Continued in Chapter 2…

[1] Former treaty port cities in China include Guangdong, Xiamen, Fuzhou, and Ningbo, among others.

[2] See Frederic Wakeman, The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China: Volume 1 (University of California Press, 1986) and The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-Century China: Volume 2 (University of California Press, 1986).

[3] This is, of course, an extremely simple interpretation of the long and complex legacy of the Qing dynasty. As Frederic Wakeman and many others have pointed out, numerous attempts were made by reformers in the Imperial Court such as Kang Youwei康有為 (1858-1927) and Liang Qichao梁啟超 (1873-1929) in the late 19th century, who briefly succeeded during the Hundred Days’ Reform of 1896. Five years later in 1901, following the disasterious outcome of the Boxer Rebellion, which led to the occupation of the capital in Beijing, the Empress Dowager Cixi and her supporters instituted the New Policies which, like the Hundred Days’ Reform, was largely modeled on the Meiji Restoration of 1868 in Japan. Following her death in 1908, however, the reforms were once again rolled back by the conservative faction that came to power. William Rowe, meanwhile, has argued that one can see strands of reform in the activities of guilds and philanthropic organizations of the late Qing dynasty, an argument which Rowe builds on the concept of the “public sphere” introduced in Jürgen Habermas’ The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society (Cambridge: Polity, 1989). Although Rowe has faced criticism from Wakeman for overestimating the automony from the Manchu state that such organizations were able to achieve, it does suggest an interesting possibility for a re-assessement of the extent of social and political reforms achieved on the level of civil society during the Qing dynasty. See William T. Rowe, “The Public Sphere in Modern China,” Modern China 16, no. 3 (1990): 309–29, Frederic Wakeman, “The Civil Society and Public Sphere Debate: Western Reflections on Chinese Political Culture,” Modern China 19, no. 2 (1993): 108–38, and William T. Rowe, “The Problem of ‘Civil Society’ in Late Imperial China,” Modern China 19, no. 2 (1993): 139–57.

[4] See Karl Gerth, China Made: Consumer Culture and the Creation of the Nation (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 2003).

[5] For background on the warlord factions, I have relied heavily on Chi Hsi-sheng, Warlord Politics in China, 1916-1928 (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1976).

[6] Arthur Waldron’s From War to Nationalism: China’s Turning Point, 1924-1925 (Cambridge University Press, 2003) is an indispensable resource for helping to understand the complex military and political situation of the mid-1920s in China, in particular Chapter 7, “The war and society.”

[7] This, and other biographical information about Ye Qianyu’s life is drawn from his autobiography Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian 葉淺予自傳:細敘滄桑記流年 [The Autobiography of Ye Qianyu: Carefully Narrating the Changes of the Ages, Recording the Passing Years] (Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe 中國社會科學出版社, 2006).

[8] Wakeman Frederic, Policing Shanghai, 1927-1937 (University of California Press, 1995), 120.

[9] Named after a famous saying attributed to Confucius: “Having three kinds of friends will be a source of personal improvement; having three other kinds of friends will be a source of personal injury. One stands to be improved by friends who are true, who make good on their word, and who are broadly informed; one stands to be injured by friends who are ingratiating, who feign compliance, and who are glib talkers” 益者三友,損者三友。友直,友諒,友多聞,益矣;友便闢,友善柔,友便佞,損矣. Roger T. Ames, tran., The Analects of Confucius: A Philosophical Translation (Random House Publishing Group, 2010), 197.

[10] For more on Ernest Major and the Shenbao, see Rudolf G. Wagner, ed., Joining the Global Public: Word, Image, and City in Early Chinese Newspapers, 1870-1910 (SUNY Press, 2012).

[11] Wang Shuyang would later work as a distributor of The Young Companion and Shanghai Sketch II, among other magazines. See Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 69.

[12] Jia Yan 賈彦, “Shangzhan yu Bingzhan: Naxie yu Sanjiao Maojin Youguan de Kangri Chuanqi” 商戰與兵戰:那些與“三角”毛巾有關的抗日傳奇 [Retail Wars and Miltary Wars: All Those Stories About Three Triangle Towels During the War of Resistance], Lishi Pindao – Dongfangwang 歷史頻道-東方網, April 18, 2014, http://history.eastday.com/h/shlpp/u1a8040028.html (accessed December 30, 2015).

[13] Unless otherwise mentioned, information about Ye Qianyu is drawn from his autobiography. All other biographical information on Ji Xiaobo is based on a short essay and two encyclopedia entries: Bu Wuchen 步武塵, “Gaoshou manhuajia Ji Xiaobo” 高壽漫畫家季小波 [Long Lived Manhua Artist Ji Xiaobo], Suzhou Zazhi 蘇州雜志, February 2002, 11–12, Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “季小波” [Ji Xiaobo], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷 (Shanxi Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 陝西人民美術出版社, November 2000), 952 and Tang Fei 庸非, ed., “季小波” [Ji Xiaobo], Zhongguo Dangdai Manhua Jia Cidian 中國當代漫畫家辭典 (Jiangsu Renmin Chubanshe 浙江人民出版社, May 1997), 617.

[14] See Huang Ke 黃可, “Sun Xueni yu Shengsheng Meishu Gongsi–jiushi huajia de shengcun zhi dao” 孫雪泥與生生美術公司——舊時畫家的生存之道 [Sun Xueni and Shengsheng Fine Arts Company: How One Artist Survived], Yishu Zhongguo 藝術中國 (September 3, 2009), http://art.china.cn/huihua/2009-09/03/content_3110162.htm (accessed March 14, 2015).

[15] Ma Liangchun 馬良春 and Li Futian 李福田, eds., “Youxi Zazhi” 游戲雜志 [The Pastime], Dictionary of Chinese Literature 中國文學大辭典 (Tianjin People’s Press 天津人民出版社, 1991), 5846.

[16] Geremie Barmé, An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975) (University of California Press, 2002), 47.

[17] Relying on Bi Keguan’s analysis, Feng’s biographer, Geremie Barmé suggests that the term manhua was chosen to distinguish Chinese cartoons from Western katong 卡通 (cartoons). In his biography of Feng, Barmé explains at length how Feng came to use this term, while also exploring the long historical legacy of the word manhua in both China and Japan. See Ibid., 89–97.

[18] Barmé records that it took over two years for the Manhua Society to adopt the term, while in fact Ji Xiaobo was describing his cartoons as manhua as early as February, 1926, some seven months after the appearance of Feng Zikai’s Manhua. See Ibid., 93.

[19] As Christopher G. Rea points out, the title of this image a double entrendre, reflecting not only the satisfied mental state of the figure, but also the “fullness” moon.

[20] It is also possible that Sun Yiwen is actually a penname of Zhu Xilang, who in addition to his courtesy name Liangren梁任and style name was緯軍, also went by Junchou君仇, Gongsun Junchou 公孫君仇, Huangdi zhi Cengceng Xiaozi黃帝之曾曾小子 (Great-great Grandson of Emperor Huangdi), and Guaigao Jushi夬膏居士, among others. See Shi Xiaoping 施曉平, “[Zhuanzai] ‘Zhu Liangren Mu’ Wuzhong Qiren_Suzhou Ribao” [轉載]“朱梁任墓”吳中奇人_蘇州日報 [[Repost] “Zhu Liangren’s Tombstone” The Wonder of Wuzhong_Suzhou Daily], March 17, 2014, http://blog.sina.cn/dpool/blog/s/blog_4a3f841e0101jals.html (accessed November 21, 2015) which appears to have been based on an undated essay by Gan Lanjing 甘蘭經, “Zhu Liangren” 朱梁任 [Zhu Liangren], Zhongguo Renmin Zhengzhi Xieshang Huiyi Jiangsu Sheng Suzhou Shi Wujiang Qu Weiyuanhui 中國人民政治協商會議江蘇省蘇州市吳江區委員會, n.d., www.wjzx.gov.cn/ (accessed November 21, 2015).

[21] One biography of Ji Xiaobo records that the local warlord at the time was Sun Chuanfang. Sun however, did not take control of Suzhou until the fall of 1925. Ye Qianyu was born in March,1907, and remembers arriving in Shanghai when he was 18, meaning that he would have met Ji in 1925, making it more likely that the warlord who shut down Zhengda Daily was in fact Qi Xieyuan.

[22] This is a rough estimate, given that his former employer Zhu Xilang at Zhengda Daily took up a new position as a professor at Nanjing Dongnan Daxue 南京東南大學 in 1924. See Gan Lanjing, “Zhu Liangren.”

[23] Christopher G. Rea points out that三角之光 can also be translated as “light from three angles,” a common lighting scheme used in photography and film.

[24] For a thorough analysis of the development of Feng Zikai’s drawing style, see Chapter 2 of Geremie Barmé’s monograph, “Journey to the East” in An Artistic Exile.

[25] Ibid., 94.

[26] For an account of the early history of lianhuanhua, see Shen Kuiyi, “Lianhuanhua and Manhua–Picture Books and Comics in Old Shanghai,” in Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books, ed. John A. Lent (University of Hawaii Press, 2001), 100–120, https://www.academia.edu/11220556/Lianhuanhua_and_Manhua–Picture_Books_and_Comics_in_Old_Shanghai (accessed October 5, 2015) and Nick Stember, “Chinese Lianhuanhua: A Century of Pirated Movies,” May 23, 2014, http://www.nickstember.com/chinese-lianhuanhua-century-of-pirated-movies/ (accessed October 5, 2015).

[27] An excellent anecdotal account of use of lianhuanhua in the PRC is available in Gino Nebiolo’s “Introduction,” in The People’s Comic Book: Red Women’s Detachment, Hot on the Trail and Other Chinese Comics (Anchor Press, 1973).

[28] Personal communication, November 11, 2015, Bevan, A Modern Miscellany, 29.

[29] For an account of the last three generations of the Chen family, see Return to the Middle Kingdom: One Family, Three Revolutionaries, and the Birth of Modern China (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2008), authored by Yuan-tsung Chen, Jack Chen’s wife. More recently, Paul Bevan has published his research on Jack Chen’s involvement in the manhua movement, which is explored in Chapter 5 of A Modern Miscellany.

[30] Bu Wuchen, “Gaoshou manhuajia Ji Xiaobo,” 11.

[31] Bu Wuchen, “Gaoshou manhuajia Ji Xiaobo.”