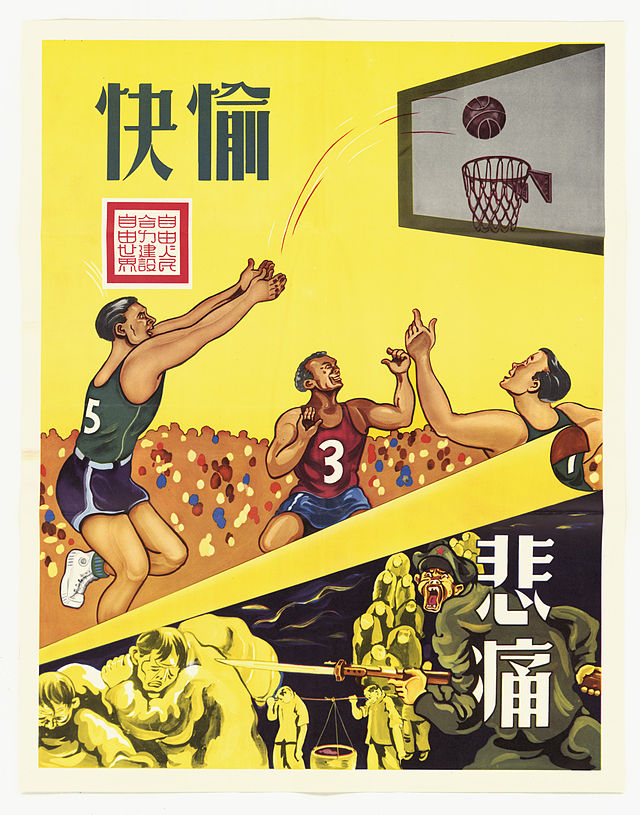

“Happiness and Misery” 愉快 / 悲痛 [Inset: Free people, join forces to build a free world! 自由人民合力建設自由世界]. Chinese language Anti-communist propaganda distributed in the Philippines in the early 1950s. Source.

“Happiness and Misery” 愉快 / 悲痛 [Inset: Free people, join forces to build a free world! 自由人民合力建設自由世界]. Chinese language Anti-communist propaganda distributed in the Philippines in the early 1950s. Source.

Bruce Lee unveils a ‘gift’ from the rival Japanese martial arts school which reads “Sick Man of Asia” 東亞病夫

Bruce Lee unveils a ‘gift’ from the rival Japanese martial arts school which reads “Sick Man of Asia” 東亞病夫

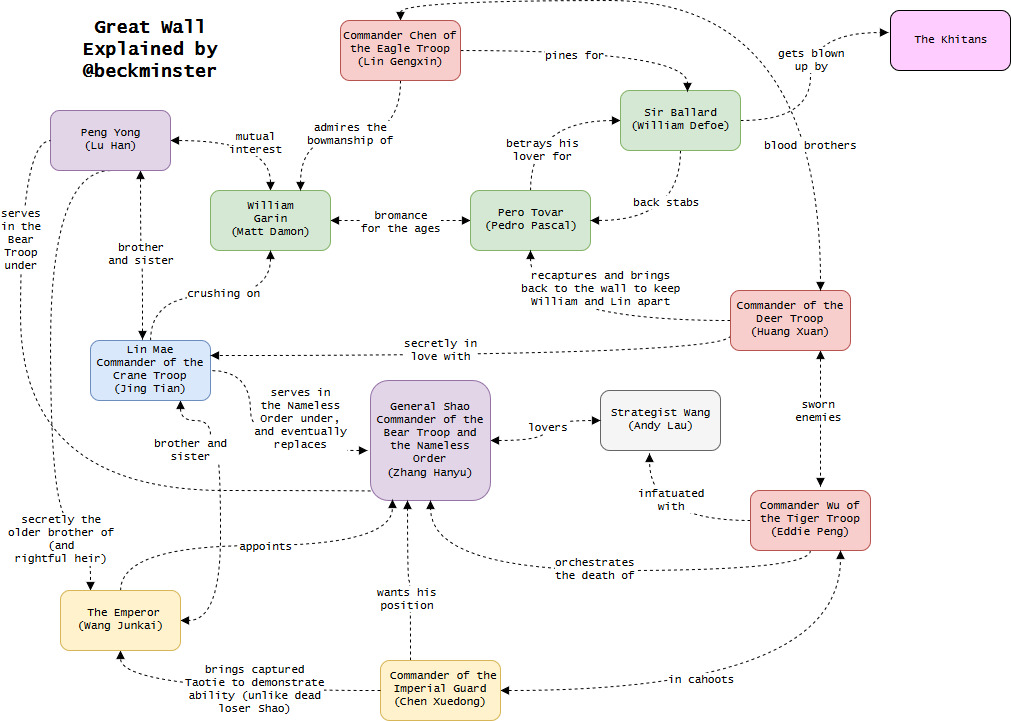

One year earlier, meanwhile, Zhang Yimou had made his own quixotic announcement: that he was in talks to direct the film which would become Great Wall.

This project had its genesis in 2012 concept by Legendary CEO Thomas Tull, and World War Z creator Max Brooks. At the time they saw the film as being about ‘the mystery and secret origin of why the Great Wall was built,’ with the protagonists a band of British soldiers (rather than mercenaries) who witness the construction of the Great Wall in mid-15th century China to keep out an invading army of monsters. For Zhang to make the film, of course, the script would have to be rewritten for a Chinese sensibilities, but still in English with American stars so that it could be a hit with Western audiences.4

Detail from a promotional poster for Great Wall. Notice how scruffy the white guys look compared to the Chinese actors.

Detail from a promotional poster for Great Wall. Notice how scruffy the white guys look compared to the Chinese actors.

As pure visual spectacle, however, the film doesn’t disappoint, and the monster slaying technology, combined with displays of Chinese athleticism and strength, is particularly inventive. In one memorable scene, giant stone spheres are transported through a wall via a serious of cranks and gears, where they are coated in a viscous fluid and set aflame before being launched by catapult into the teaming demon horde. Scissors emerge from the wall, cutting the climbing taotie in two, and flaming arrows are employed to great success.

In another, female soldiers, dressed in brilliant blue uniforms, launch themselves off of platforms (visible in the lower left-hand corner of the above image, and below) while holding long lances which they embed into the writhing forms of the taotie. Few of the soldiers survive their plunge into the abyss, but their compatriots seem to have neither the time nor the the capacity for remorse. They are color-coded automatons, their movements as precise as any robot or machine.

Separate from the hyper-masculine salvation of Bruce Lee, technology has similarly long been promoted as offering salvation of the nation. Late-Qing intellectuals Liang Qichao 梁啓超 (1873-1929) and Kang Youwei 康有爲 (1858-1927), for example, advocated for the adoption of ‘science and democracy,’ and the books of Jules Vernes were translated and widely disseminated.

But author and polemicist Lu Xun 魯迅 (1881-1936, himself an early translator of Verne) rejected both physical strength and technology. As he famously wrote in late 1922, describing a harrowing experience in the lecture hall of a Japanese medical school:

“I do not know what advanced methods are now used to reach microbiology, but at that time lantern slides were used to show the microbes; and if the lecture ended early, the instructor might show slides of natural scenery or news to fill up the time. This was during the Russo-Japanese War, so there were many war films, and I had to join in the clapping and cheering in the lecture hall along with the other students. It was a long time since I had seen any compatriots, but one day I saw a film showing some Chinese, one of whom was bound, while many others stood around him. They were all strong fellows but appeared completely apathetic. According to the commentary, the one with his hands bound was a spy working for the Russians, who was to have his head cut off by the Japanese military as a warning to others, while the Chinese beside him had come to enjoy the spectacle.

“Before the term was over I had left for Tokyo, because after this film I felt that medical science was not so important after all. The people of a weak and backward country, however strong and healthy they may be, can only serve to be made examples of, or to witness such futile spectacles; and it doesn’t really matter how many of them die of illness. The most important thing, therefore, was to change their spirit, and since at that time I felt that literature was the best means to this end, I determined to promote a literary movement.”

我已不知道教授微生物學的方法,現在又有了怎樣的進步了,總之那時是用了電影,來顯示微生物的形狀的,因此有時講義的一段落已完,而時間還沒有到,教師便映些風景或時事的畫片給學生看,以用去這多余的光陰。其時正當日俄戰爭的時候,關於戰事的畫片自然也就比較的多了,我在這一個講堂中,便須常常隨喜我那同學們的拍手和喝採。有一回,我竟在畫片上忽然會見我久違的許多中國人了,一個綁在中間,許多站在左右,一樣是強壯的體格,而顯出麻木的神情。據解說,則綁著的是替俄國做了軍事上的偵探,正要被日軍砍下頭顱來示眾,而圍著的便是來賞鑒這示眾的盛舉的人們。

這一學年沒有完畢,我已經到了東京了,因為從那一回以后,我便覺得醫學並非一件緊要事,凡是愚弱的國民,即使體格如何健全,如何茁壯,也隻能做毫無意義的示眾的材料和看客,病死多少是不必以為不幸的。所以我們的第一要著,是在改變他們的精神,而善於改變精神的是,我那時以為當然要推文藝,於是想提倡文藝運動了。

– From the preface to A Call to Arms 呐喊.

‘Futile spectacles’ aside, this image of microbes might be the best metaphor yet. As Carlos Rojas argues in his monograph on the Great Wall, the monolithic image of the wall which most of us are familiar with is largely a 21st century mental construction. There is no one wall, with the actual structure consisting of a series of fortifications and rammed earth ridges which mostly date back to the Ming dynasty.

Nor was the wall meant to be impenetrable, serving more as expression of imperial power, early warning system (via signal fires), and transportation route for troops and supplies.

In this sense then, it might be better to think to think of the wall as biological, in the sense of a cell wall. In this reading, the various troops of the film (“melee-specialist Bear Troop, acrobatic-specialist Crane Troop, archer-specialist Eagle Troop, siege engine-specialist Tiger Troop, and horse-mounted Deer Troop”) become the immune system of a living, biological system: the skin, the lymph, the red and white blood cells, the inflammation producing eicosanoids and cytokines, the phagocytes which engulf and consume pathogens. 5

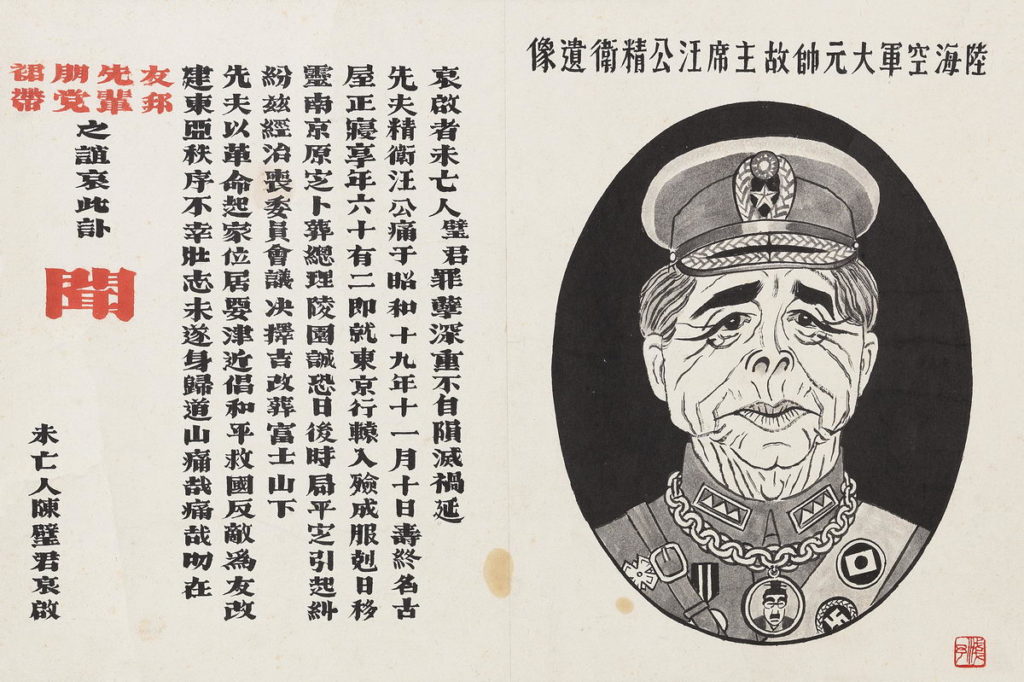

“Bacteria from the ‘Sick Man of Asia’ at 2000x Magnification” Modern Sketch, .

Certainly the taotie, which in this reading would be the pathogens (ie bacteria, viral infection, fungi), are obviously biological, almost excessively so:

Human technology is portrayed as a hard, sharp thing which embeds itself into the bodies of the taotie, who bleed copious amounts of green gore:

But that same technology is shown to be powered by sweating, breathing humans who run the cranks and in sense become the wall, or biological extensions of it. Humans kill with technology, they shield themselves with technology, but without humans to make use of this technology the things themselves are inert. The problem becomes, if technology and structures are biological, then they are open to infection and subversion.

This is perhaps why the film doesn’t show the Great Wall being built–as was suggested in the original treatment by Tull and Brooks. The wall’s impermeability is suggested by its ancientness, and by its sheer physicality. It looks immovable and impenetrable, almost beyond human comprehension. It is nearly as alien to the humans inhabiting it as the taotie are. But this sense of security proves to be built on a false foundation: Like Tijuanan traffickers, the taotie tunnel under the wall and make their way to the heart of the nation, the Imperial Capital, where the taotie use walls of flesh to protect their queen (a formation mimicked by the humans, when they attempt to deal with a lone taotie on the wall in an earlier scene):

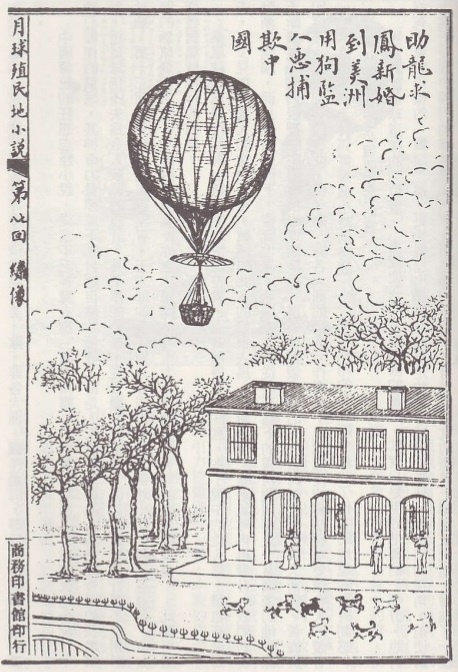

When it comes time to abandon the wall, hot air balloons (pictured in the far left of the above image) also feature prominently in the film, scattering to the wind like flaming, silkpunk dandelion seeds. Thanks to Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, hot air balloons quickly became a symbol of Western technology during the late-Qing, with one of the first Chinese science fiction novels, Lunar Colony 月球殖民地小說, featuring a man who travels to the moon in one:

Lunar Colony 月球殖民地小說 by Old Fisherman of the Secluded River 荒江釣叟 (1904)

Lunar Colony 月球殖民地小說 by Old Fisherman of the Secluded River 荒江釣叟 (1904)

Monsters (well, ghosts and demons) were also a big concern in the pictorials of the late Qing, which may have been code for anxieties about racial purity vis a vis the fate of the nation–or may have just been fun to draw. The fact that these anxieties are resurfacing now though, in a time when national borders are once again becoming a contested space and rate of social change is outpacing our ability to adapt to it, seems to be more than just a coincidence. From Brexit, to Trump’s Yuge Wall, we seem to be entering a period of turmoil precisely when our global and regional biological systems have reached a crisis point.

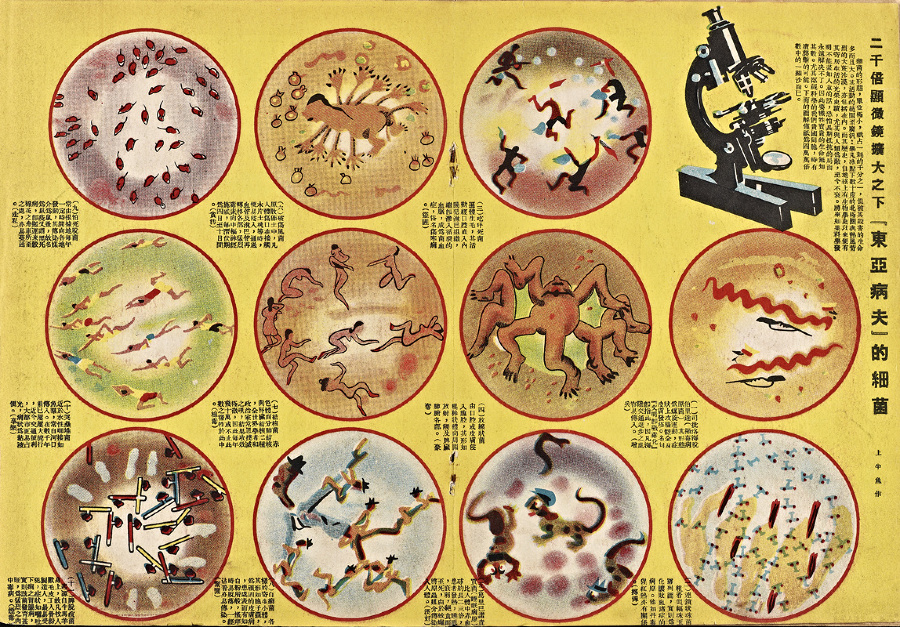

So, while the message of “Resist!” might have captured the popular imagination, the image of the collaborator who “saves the nation through twisted means” may prove to be a more useful analogy for understanding the strange times in which we find ourselves. All systems resist change, but all systems are equally open to infection, and co-opting–and even terrible blockbuster films can be sites of fruitful exploration if we scratch (or tunnel, as the case may be) below the surface.

EDIT 2/28/2017: Re-thinking this piece after I posted it last night, it struck me that there is another way we might apply the concept of ‘traitor’ to the film: the idea that William (Matt Damon’s character) is a race traitor. The incredulous reactions of Tovar (Pedro Pascal) and Sir Ballard (William Defoe) to his decision to stay and fight (rather than betray their captors by stealing the black powder) would seem to support this reading. The tension between biological loyalty and loyalty to a cause is made even more explicit in the treatment of the interracial relationship between William and Commander Lin Mae (Jing Tian). Interestingly, subverting Hollywood convention, the characters don’t end up together at the end of the film, perhaps in a nod to Han chauvinists.

Digging a little deeper, one also finds the concept of quisling, or ‘collaborator’ (from the Norwegian war-time leader and Nazi collaborator, Vidkun Quisling) cropping up in Max Brook’s original novel for World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War:

Joe: “The biggest problems were quislings.”

Interviewer: “Quislings?”

Joe: “Yeah, you know the people that went nutballs and started acting like zombies. […] As I understand it, there’s a type of person who just can’t deal with a fight or die situation. They’re always drawn to what they’re afraid of. Instead of resisting it, they want to please it, join it, try to be like it…. or like in regular war when people who are invaded sign up for the enemy’s army….

“I think the saddest thing about them is that they gave up so much, but in the end lost anyway, cause even though we can’t tell the difference between them, the real zombies can…eye witness accounts and even footage of one zombie attacking another. Stupid. It was zombies attacking quislings, but you never would have known that look at it. Quislings don’t scream. They just lie there, not even trying to fight, writhing in that slow, robotic way, eaten alive by the very creatures they’re trying to be.”

In Great Wall, ‘nutballs’ is precisely how Tovar and Sir Ballard treat William after he sides with Lin Mae and the Nameless Order.

EDIT 3/2/2017: Okay, I think I’ve figured out the film now:

- Tried very hard not to make a 日本鬼子 comment here, but it does seem relevant to point out that in the PRC the Japanese, to this day, are referred to as ‘devils’ or ‘demons’ in casual conversation. [↩]

- This quote may very be apocryphal. The Chinese appears to be a back translation from English, which fits with the fact that the most convincing source appears to be a June 30, 1941, letter from Ernest Hemingway to Henry Morgenthau, United States Treasury Secretary. Hemingway had accompanied his then wife, the journalist Martha Gellhorn, on a trip to wartime capital of Chongqing in spring of that year, where they had both met Chiang Kai-shek. In the letter, however, he simply quotes a ‘KMT official,’ not the Generalissimo himself. See “In love and war: a Hong Kong honeymoon for Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn,” Post Magazine, February 13, 2016. [↩]

- Transcript and video available here. [↩]

- See “Zhang Yimou in Talks to Direct Legendary’s ‘Great Wall’ (Exclusive).“ [↩]

- In this reading, I have to confess to being inspired by Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, which I am in the middle of reading at the moment. [↩]