Between World War I and World War II China experienced it’s first boom in the production and appreciation of cartoons and manhua. Although several notable cartoon and proto-cartoon publications predate World War I (and more importantly in China, the collapse of the Qing in 1911),1 it is the 1920s and 1930s which saw comic strips and cartoons reach their highest social currency in China, one that has perhaps yet to be rivaled even today.

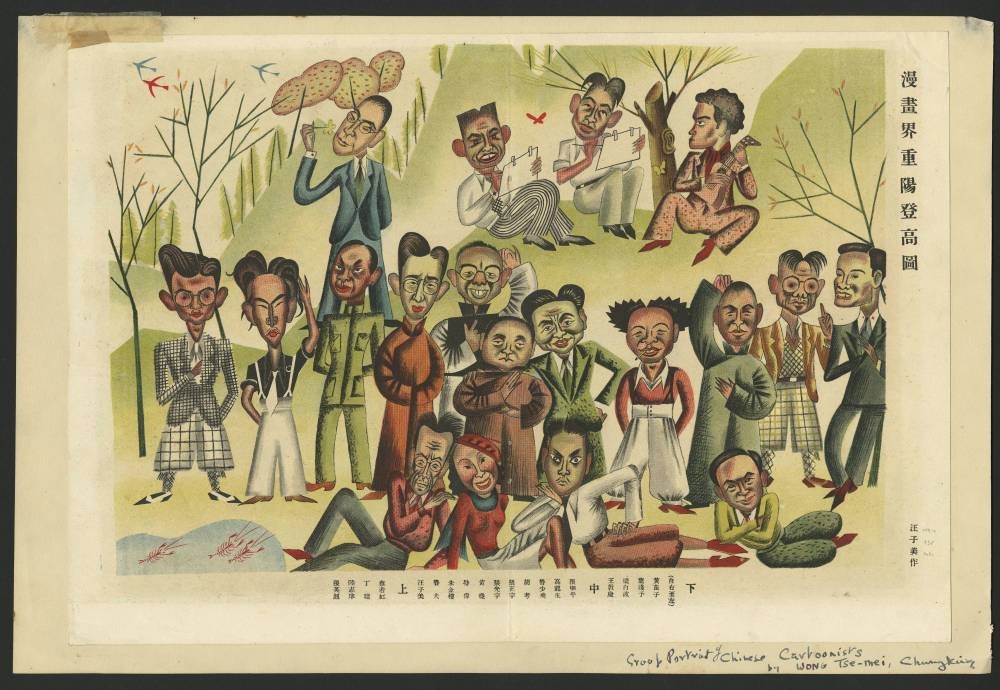

In large part this is thanks to the work of a group of loosely affiliated artists, writers, and publishers who collaborated on several key publications produced primarily (but not exclusively) in Shanghai. Many of them are featured in this 1936 illustration by Wang Zimei , :

The cartoon circle climbs the mountains for Double-Ninth 漫畫界重陽登高圖

According the caption, they are (from left to right):

Bottom row: Wang Dunqing王敦慶 (1899-1990), Liang Baibo 梁柏波 (?1911-70),Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-95), Huang Miaozi 黃苗子 (1913-2102)

Middle row: Wang Zimei 汪子美, Lu Fu 魯夫, Zhu Jinlou 朱金樓, Te Wei 特偉 (1915-2010), Huang Yao 黃堯 (1917-87), Zhang Guangyu 張光宇(1902-65), Zhang Zhengyu 張正宇 (aka Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇 1903-76), Hu Kao 胡考 (1912-94), Lu Shaofei 魯少飛 (1903-95), Gao Longsheng 高龍生, Zhang Leping 張樂平 (1910-92)

Top row: Zhang Yingzhao 張英趙 ,Lu Zhixiang 魯志庠,Ding Cong 丁聰 (1916-2009), Cai Ruohong 蔡若虹 (1910-?)2

As I am currently in the process of writing my MA thesis on the networks of economic and social capital which made manhua periodicals possible during this time period,3 most of these names are very familiar to me. Wang’s illustration, however, is the first time I’ve seen them all in one place.

If the date attributed to the illustration is correct, this drawing was produced during the final year of the period of relative peace and prosperity which Shanghai had enjoyed from the time of its founding as a patchwork of extraterritorial foreign concessions following the Opium Wars of the late 19th century. It would all come crashing down on August 13, 1937, with the Japanese bombing and invasion of Shanghai.

For nearly 6 weeks of KMT troops engaged in pitched battles with Japanese forces on the streets of the “Paris of the Orient.” As the Nationalist government lacked the resources and capital to fight the well-trained and highly industrialized Japanese military, the so-called Battle of Shanghai was designed to bring international attention to China’s plight and hopefully galvanize the League of Nations to come to China’s defense. Unfortunately, although a conference was eventually convened in November in Belgium (well after the fall of Shanghai to the Japanese) on the basis of Nine Powers Treaty, both Japan and Germany refused to participate, and nothing of note was accomplished.

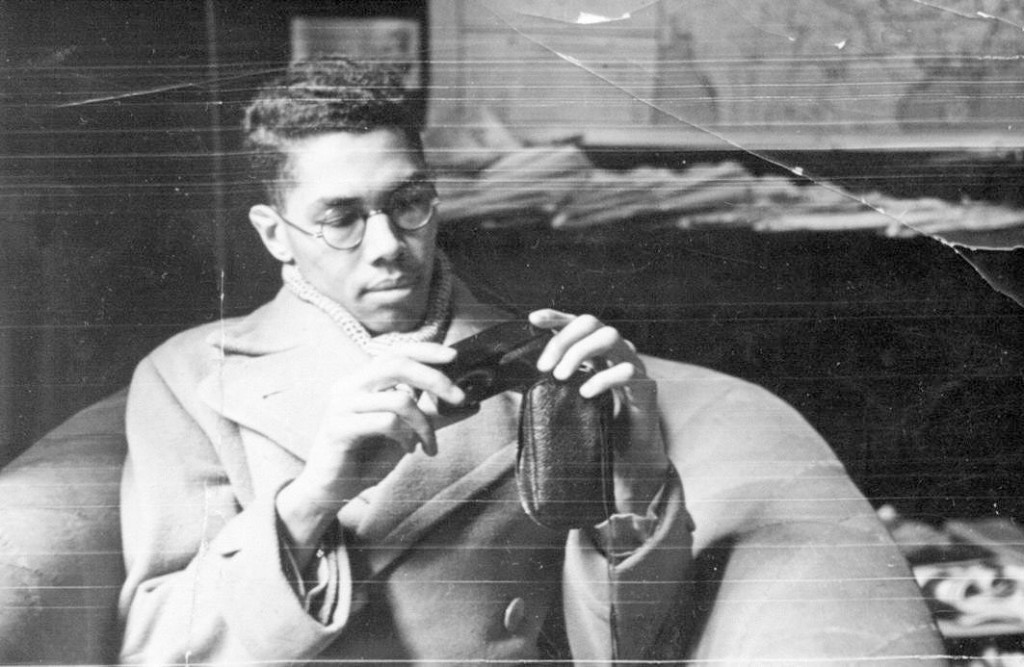

It appears that we have this conflict, however, to thank for inspiring journalist, cartoonist, and world traveler Jack Chen 陈依范 (1908-97) to bring this illustration and a number of others to Europe, where he organized and exhibition in support of the anti-Japanese Cartoon Propaganda Corps.4

Like many of the journalists who covered China in the early 20th century, Jack Chen was (to borrow a phrase from Neal Stephenson) a stupendous badass. Born in 1908 in Trindad to Sun Yat-sen’s future foreign minister, Eugene Chen 陈友仁, and his first wife, Agatha Alphosin Ganteaume, Chen first arrived in Shanghai in 1927 apparently having spent most of his childhood with his mother in London. Shortly there after the 19 year-old Jack was sent to Moscow, along with his older brother Percy, where Jack (probably under the influence of Anna Louise Strong) began his career in journalism. After returning to China, Chen fell in with the crowd of troublemakers pictured above, eventually traveling to the Communist base in Yanan in 1938 with Hu Kao (see above, middle row fourth from the right, with the crazy hair), where they were later joined by the influential cartoonist Hua Junwu 华君武 (1915-2010). In May of the same year, Chen wrote an expose on the Chinese cartooning movement for ASIA Magazine, which began, perhaps somewhat tongue in cheek:

Six years ago there was no cartooning in China worth writing about. It is one of the youngest modern arts that have grown out of China’s struggle to master the progress of the West and yet retain her soul. And it bears all the marks of that struggle.

It was persecuted from birth by the reaction that then sat in the saddle of government, and even in 1936, in October, when the first national exhibition of cartooning was held in Shanghai, old-fashioned esthetes still called it disdainfully, in the colorful “scholars” colloquial, “a small means of cutting up insects”–that is to say, an inconsequential art. Yet by then more than a dozen cartoon magazines were being published, delighting readers in all the main cities and playing an important part in the modern national movement. The Shanghai exhibition attracted more attention than any proceeding art show, even the venerable Lin Sen, President of the Republic, smiled approval.

In August, 1937, the Japanese invasion threatened the main technical base of the cartoonists in Shanghai. They mobilized in the government propaganda units in defense of their country and their cartooning: for one thing was evident–Japanese domination spelled the absolute suppression of modern art in China, cartooning included.

Such is the brief history of this newcomer to the ancient arts of China. Yet a consideration of it gives a vivid insight into contemporary China–for this is above all an art of the present, and therefore an immediate signpost to the future.5

Although I can’t say I agree with Chen’s assessment of the state of Chinese cartooning in 1932, nor can I entirely set aside his political bias6 his article provides a unique perspective on an important transition period for Chinese manhua artists, as they moved from being entrepreneurs to propagandists. For example, Chen mentions that of the ten7 founding members of the earlier Manhua Society, formed in the late 1920s,

…one died with enough money to pay for his funeral; one joined the government and secured a job that kept him from doing embarrassing cartoons, one disappeared after publishing a particularly pointed anti-Kuomintang cartoon, six managed to hold together, to be joined by a seventh who had been in hiding for four years during the bitterest persecution of Leftists: after the fall of the Wuhan government in 1927 and the split of the united front between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang. Their survivors met at the home of their dead friend, whither that all unknowingly come on the same mission–to give him a regular funeral. Of the seven, three had steady jobs that paid fifty dollars gold a month, and they earned perhaps fifty more by extra work. These are the best paid cartoonists in China. The rest scrape along as best they can, editing, teaching, doing odd jobs. And yet–making cartoon history.

Of these I can only identify Huang Wennong 黄文农 (1903-1934) as the one fortunate enough to have been able to pay for his own funeral.

[EDIT 1/18/15: I recently discovered that the cartoonist who Chen refers to as having joined the government was Lu Shaofei 鲁少飞. According to a 1994 essay by Bao Limin 包立民, Lu served as a KMT official in Lanzhou during the 1940s, acting as the director of the Lanzhou Municipal Social Services Department 兰州市社会服务处 from 1941 to 1949. In August, 1944, Lu traveled to Chongqing to organize an exhibition of artists from Xinjiang 新疆, where he had lived from 1938 to 1941, working as the art director of the Xinjiang Daily 新疆日報. While in Chongqing, Lu is said to have approached Ye Qianyu about the possibility of helping him find employment in Chongqing. According to Bao, Ye discouraged Lu from moving to Chongqing first because he was worried that it would be difficult for Lu to support his family (at this point Lu was married with a daughter and son) in the temporary capital, and secondly because Ye believed that the Japanese defeat was imminent, and so it would be better to wait. After the CCP came to power in 1949 Lu returned to Shanghai with his family, but had trouble finding employment. Ye, meanwhile, was invited by the famous painter Xu Beihong 徐悲鸿 to teach at the National Art School in Beiping 國 立北平藝術專科學校, which merged with the Department of Fine Arts at North China University 華北大學 in 1950 to become the Central Academy of Fine Arts 中央美術學院. When Lu wrote Ye seeking an introduction to Xu, Ye responded by criticizing Lu for his involvement with the KMT government and refused to help. 8]

In his autobiography, Ye Qianyu (bottom row, second from the right) records that began his career in submitting cartoons to the periodical Three Day Cartoons 三日漫畫, which was shut down by the KMT following the April12 1927 crackdown. 9 Afterwards, Ye worked as the “odd job man” 跑腿 for the first incarnation of Shanghai Manhua 上海漫畫, a broadsheet with drawings by Huang, and edited by Wang Dunqing (bottom row, first on the left), who was also working as a middle school teacher at the time.

Shortly there after, probably in late 1927, Ye co-founded the Manhua Society with Ding Song 丁悚 (1891-1972, father of Ding Cong, top row, second from the right) and the Zhang 張 brothers, Guangyu 光宇 (middle row, sixth from the left) and Zhengyu 正宇, all of whom happened to live in the same neighborhood in Shanghai at the time, near Rue Admiral Bayle 貝勒路.

[EDIT 1/18/15: According to Bao, Ye is mis-remembering the order of events here because the Manhua Society was founded in the fall of 1927 before Shanghai Manhua began being published. The disagreement seems to stem from the fact that there were two publications with the name Shanghai Manhua, the 1927 broadsheet, and the 1928 magazine. At any rate, Bao agrees with Ye that the first meeting of the Manhua Society was held at Ding Song’s house in Tiantili Alley 天梯裏 off of Rue Admiral Bayle. Ye was invited, as were the oldest and youngest Zhang bothers, Guangyu and Zhengyu, (the middle Zhang brother, Cao Hanmei 曹涵美, nee Zhang Meiyu 張美宇 was apparently not present for this meeting) who lived in Hengqingli Alley 恆慶裏 on the opposite side of Rue Admiral Bayle. Rounding out the party were Huang Wennong, Ji Xiaobo 季小波, Cai Shudan 蔡输丹, and either Hu Xuguang 胡旭光 or Wang Yisan 王益三 (Bi Keguan 毕克官 records the former, Ji Xiaobo and Lu Shaofei the latter). Lu Shaofei was not invited, but happened to show up just as they were about to take a picture, having just returned from out of town.]

Together with the Zhang brothers, Ye would relaunch Shanghai Manhua 上海漫畫 in 1928 as a full color magazine. Wang Dunqing was originally involved with the relaunch, but quit after an argument with Zhang Zhengyu, following which he allegedly didn’t speak to the members of the Manhua Society for three years. This break lasted until he was convinced to join the millionaire playboy and erstwhile romantic poet Shao Xunmei’s 邵洵美 (1906-1968)10 would-be publishing empire, the Modern Press 時代圖書公司 in 1931, co-founded with the three Zhang brothers one year after Shanghai Manhua had been absorbed by Shao’s Modern Pictorial 時代畫報. 11

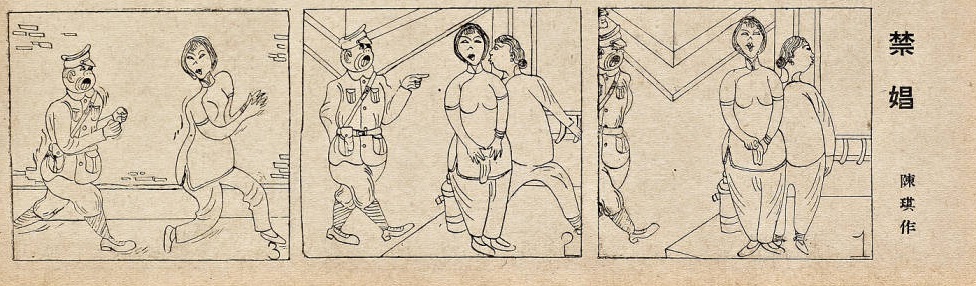

Interestingly, while most academic studies and popular histories have focused on the political content of these manhua periodicals, Jack Chen is quick to point out that although, yes, there is a great deal of political satire, “…this is most essentially a man’s art, which indulges in what is best described as ‘Elizabethan coarseness.’ There is a necessary amount of eroticism, influenced to a large extent by journals such as the American Esquire, but with an element of quite Chinese abandon.”12 For an example of this, consider, the first three panels of the following cartoon “No Prostitution” 禁娼 by Chen Qi 陳琪:13

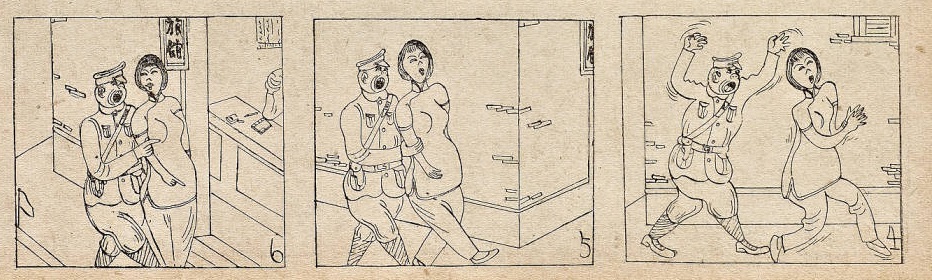

When we turn the page however, it is revealed that the police officer was chasing after the prostitute not to arrest her, but was instead intending to escort her to a cheap hotel:

Surprisingly, the work of the these pioneering cartoonists is mostly unknown in mainland China today, with most young people conflating manhua with manga, since both are written with the same characters in Chinese, and since Japanese cartoons have more or less dominated since the late 1980s. In a 2011 article on contemporary mainland Chinese comics, Nadim Damluji spends much of the article contrasting the cartoonists of the Republican era with those of today, focusing on Chairman Ca 擦主席, the editor of the underground Chinese comics anthology Cult Youth. Ca tells Damluji that, “Growing up here we come into contact with more Japanese comics. Only after the Internet became prevalent did we learn about European or North American comics.”14 While Damluji finds this deeply ironic, and perhaps somewhat disappointing, I am hesitant to romanticize the artists from the 1930s. As can seen from above, manhua legends such as Ye Qianyu, Wang Dunqing, and Zhang Guangyu were not above petty squabbles and trying to make buck from salacious content.

- For example The China Punch was an early cartoon magazine produced in Hong Kong, and Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari the Dianshizhai Pictorial 點石齋畫報 were both published in Shanghai durin the last decade of the 19th century. For more on China Punch and Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari see Christopher Rea’s essay “He’ll Roast All Subjects That May Need the Roasting’: Puck and Mr Punch in Nineteenth-Century China.” in Asian Punches, edited by Hans Harder and Barbara Mittler, 389–422. Berlin: Springer, 2013. For more on the Dianshizhai Pictorial, see Rudolph Wagner’s chapter “” in Joining the Global Public: Word, Image, and City in Early Chinese Newspapers, 1870–1910 . Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. [↩]

- Dates and image courtesy of Mary Ginsberg and Paul Bevan at the British Museum. who included this image among others collected by Jack Chen in the exhibition The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda, on display May-Sep 2013. [↩]

- The research question I am trying to answer is: For what reason (or reasons) did manhua magazines cease publication in 1930s Shanghai? I believe that I can plausibly answer this question by completing a close reading of a selection of manhua periodicals, combined with biographical research into the contributors and publishers, and historical research into the economic and political realities of 1930 Republican era China. Another way to put this is that I am attempting to write a typology of failure for manhua magazines, ergo my working title “ [↩]

- For more on this group, see John Lent and Xu Ying’s article “Cartooning and Wartime China: Part One — 1931-1945” published in the International Journal of Comic Art, Vol. 10, No. 1, Spring 2008. [↩]

- Jack Chen, “China’s Militant Cartoonists,” ASIA Magazine, May 1938. http://www.huangyao.org/837.html [↩]

- After returning to England in 1947, Chen joined the Communist Party of Great Britain and began working as a reporter for the Worker’s Daily. In 1947, he founded what would become the the London office of the Xinhua News Agency (reputedly at the behest of the Great Helmsman himself), and in 1950 he moved back to China with his wife, I-wan, where he lived and continue to work as journalist and cartoonist until 1971. For more information on Chen see page 3 of Linda Chen’s 2013 Sino-US.com article, “Sincere friends of true communists of China – Eugene Chen family,” available online here. [↩]

- According to Ye Qianyu’s autobiography, written late in in his life, there were only seven founding members of the Manhua Society 漫畫會. According to Ye, this group formed the core of the later, and much larger, Manhua Mutual-Aid Society 漫畫協會 organized in 1935. See 葉淺予 《細敘滄桑記流年》 (江苏文艺, 2012), 107-108 [↩]

- See Bao Limin 包立民. “Ye Qianyu and Lu Shaofei (Part II)” 叶浅予与鲁少飞(下) in Meishu zhi You 美术之友 no. 04 (1994): 34–37. [↩]

- See also Ellen Johnston Laing’s “Shanghai Manhua, the Neo-Sensationist School of Literature, and Scenes of Urban Life ,” published by the Published by the MCLC Resource Center, October, 2010, available online here. [↩]

- See Jonathan Hutt’s “Monstre Sacré: The Decadent World of Sinmay Zau 邵洵美” in the China Heritage Quarterly (No. 22, June 2010) for an account of the rise and fall of the great Shao Xumei, available online here. [↩]

- For an introduction to another Shao publication, Modern Sketch 時代漫畫 see John A. Crespi’s “China’s Modern Sketch: The Golden Era of Cartoon Art, 1934-1937” unit on MIT’s Visualizing Cultures website, available online here. [↩]

- Chen, 311. [↩]

- Source: Modern Sketch, No. 39, pg. 17-18, published June 20, 1937, available online here courtesy of the Colgate University Libraries Digital Collections. [↩]

- See “Can The Subaltern Draw?: Defining Manhua -or- A Translated Marketplace in Contemporary China,” posted to the Hooded Utilitarian blog June 1, 2011, available online here. [↩]

Pingback: The Interbellum Manhua Boom – Nick Stember | CleverJots

Pingback: The Many Faces of Sun Wukong - Nick Stember