So it’s been a while since I posted on here (more than a year!) and I’m afraid I don’t have much to report about Chinese comics, for the moment at least. It’s a been a big year: after five fantastic years in Canada, my wife (Chinese) and I (American) finally successfully applied for permanent residence…and then more or less right away moved to the UK. We’d actually decided on the move before we found out if our PR application was approved or not – mostly because if it was denied, we would have to leave anyways, since our work visas were going to expire in the spring of 2019.

On the other hand, since my wife, Ding, is still working for her (and my former) Canadian employer (doing educational tourism for university students from China) under the current rules, we can keep our PR valid until we move back to Canada in a couple of years. (We love it here, but we’re worried if we stay in the UK we won’t be able to get on an equivalent path to citizenship. Also, the cost of living in London is ridonkulous.)

The other outcome of this move was that I decided to apply to go back to grad school for my PhD. I had been on the fence about whether I wanted to do that for a while, and a couple of things conspired to convince me to take the plunge — the most important being that Ding was onboard with the whole ‘more school’ thing.

When we moved to Vancouver from Shanghai, Ding had just graduated from uni, where she studied graphic design. At the time her English was only so-so, because we mostly spoke Chinese at home (my fault). That first year was probably the hardest thing we’ve ever had to get through as a couple – a strike delayed her visa indefinitely, and we ended up having to rent an apartment in Blaine, WA for two and half months while I commuted up to class at UBC, first by biking across the border to White Rock, and then taking a bus to another bus, followed by another (much shorter) bike ride to my department.

Even after we were able to get Ding’s entry visa to Canada sorted and (miracle of miracles) move into campus housing (albeit with roommates) but she still wasn’t allowed to start working. When my wife’s work visa finally arrived in the mail two months later, the only job she could find was waiting tables at a late-night Chinese restaurant. It wasn’t exactly the career she had been dreaming of.

Thinking about my wife, and the sacrifices she was making for me, there were a lot of times during that first year that I thought we’d made a huge mistake. It wouldn’t just have been easier for us to stay in China, but it seemed like we probably would have been a lot happier, too.

Fortunately, things did take a (significant) turn for the better. I was able to pick up extra work as a translator and tour guide, and those (very random) connections led to an internship for my wife, which turned into a full-time job. One thing led to another – I finished writing my MA thesis on Shanghai cartoonists in the 1920s and graduated, while my wife was promoted (after some twists and turns) to her current position in London. Where, I have to say, we are pretty dang happy.

I should probably clarify here that my decision to not apply to continue on to the PhD program in Asian Studies at UBC when I graduated in early 2016 was a personal one. Between my (next-level wizard) advisor, Chris Rea, and supervisor, Wang Qian, who I had the exceedingly good fortune to TA throughout my time at UBC, I couldn’t have asked for better advocates and teachers. (And those are only two people at the head of a very long list of people who made grad school possible, intellectually, emotionally, and financially.)

The problem I had when I was finishing my MA, was that the more I thought about it, and the more read about it, the more I wondered if I shouldn’t try something different first. A PhD is a huge time commitment, and it takes a phenomenal amount of hard work and good luck, not to mention intellectual, emotional, and financial support (on that point, see below) to get past the finish line. The same is even more true of being on the job market, and winning tenure (if such a thing still even exists by the time I get there).

Added to that, throughout my MA I struggled to use theory in my academic writing. In grad school, it often feels like the worst thing you can say in seminar is not that you didn’t do the reading, but that you didn’t understand it. And oh my lord, there were so many readings I didn’t understand! Faced with the many-headed hydra of ‘postmodern cultural Marxism,’ as much out of fear of being exposed as fraud as anything else, my response was to discount difficult writing as an obtuse crutch for a paucity of thought. Which is to say, I was half-convinced that people were just making it up to look smart — in large part because I was terrified that someone might accuse me of doing the same thing.

So instead, for the last three years (as most people who read this blog already know) I worked as a freelance translator, tour guide, editor, web designer and just about anything else that a) looked fun and b) (ideally but not always) could pay me a little for my trouble. It wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t any harder (or less fun) than grad school, either. By another stroke of luck, last year I was invited to help launch The China Channel at the LA Review of Books, alongside Alec Ash and Anne Henochowicz (with Jeff Wasserstrom and Eileen Chow pitching in as well). I also got to help set up an exchange program and spent the last two summers flying around China to talk about that, and other random things. In a lot of ways, I could see myself having continued down the rogue China-hand path indefinitely.

So why go back for the PhD?

In a sense, I think I wanted to prove that if I could, other people outside of the academic mainstream could too. Even after finishing grad school, I continued translating and writing journal articles and going to conferences and giving talks, mostly because I enjoyed doing these things. I don’t like the idea that a person needs to be in grad school, or at teaching at a university to participate in these conservations, but it’s also hard to advocate for that kind of change from the outside looking in.

Trying to introduce things that were made for a general audience, like comics and trashy movies, to an academic audience (in a convincing way, at least) actually turns out to be much harder than going the other way, which was one of the goals we set for ourselves when we launched the China Channel. The whole idea there was to publish things for people who knew nothing about China, and maybe only had a few minutes to skim a short article. So even when we had academics writing for us, we pushed them to write as clearly (and succinctly) as possible. The China Channel has been going from strength to strength, in large part because of all the academics and other smart and generous folks who have pitched in to help out.

I think both of these things (bringing academia to the people, and the people to academia) are important, but to the address the provocative (and not entirely accurate title of this post) right now I’m particularly concerned with finding a way to foster and legitimize academic discussions about work outside of the Western canon that goes beyond simply creating a new and more diverse canon to replace it. (Although that’s a good first step!)

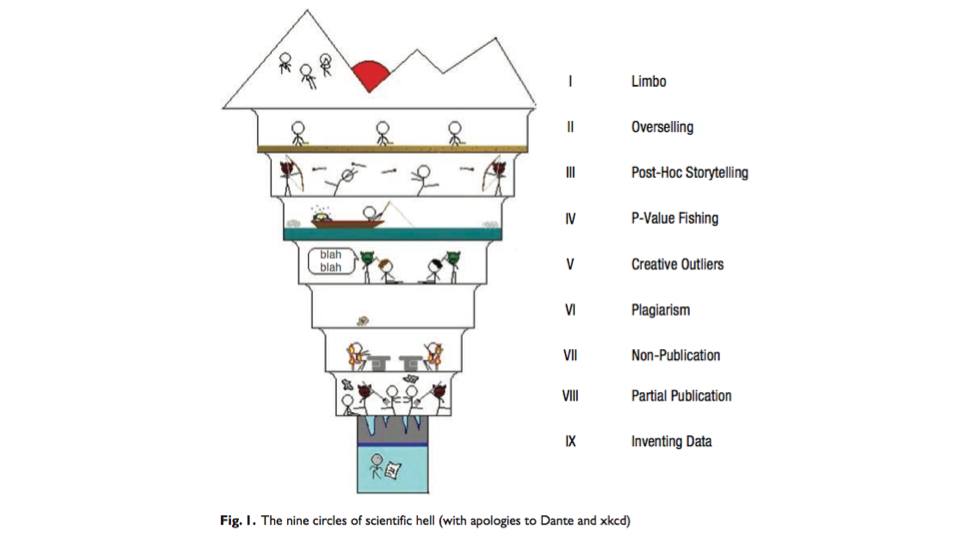

More specifically, over the last two years I’ve been thinking and reading a lot about the rise of the alt-right, especially in my own corner of the culture, in the form of Gamergate, the Sadpuppies, the red pill, incels, and other forms of toxic masculinity disguised as ‘wanting things to stay the same.’ I see a lot of the same logic at work with intellectual dark web folks like Jordan Peterson, and even with more moderate (and substantially more intelligible) academics like Steven Pinker and Jonathan Haidt. (Incidentally, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all three of these men are social psychologists of one stripe or another. As the on-going replication crisis has shown, there’s a lot of dodgy data out there waiting to be cherry-picked or p-hacked for a cause.)

Critical theory, for all of its detractors, is built around the very sensible idea that societies – just like the people who live in them – change over time. As Peter Barry argues in Beginning Theory, even the most convoluted critical theory can be boiled down to making one of the following five basic (and pretty rational IMO) points:

- Meaning is contingent [ie socially constructed]

- Politics is pervasive [it’s impossible to eliminate bias completely]

- Language is constitutive [it shapes the way we think, and therefore organize our societies]

- Truth is provisional [our understanding of the world, or a text, can’t be pinned down]

- Human nature is a myth [there are many equally good ways to organize society rather than only one best way, based on immutable truths about ‘the way we are’]

2018 was, admittedly, something of a dumpster fire, overall, and I don’t want to downplay any of the seriously troubling developments of the past year.

With that caveat in mind, I largely agree with Pinker (and also the late Hans Rosling) that there are a lot of signs that humanity is headed in the right direction, and that in so far as it rejects ideologies of hate that divide people into largely arbitrary genders, races, nations, or classes critical theory is a part of that project. Globally, I’m encouraged by the spread of democracy; the dramatic fall in infant mortality rates; and the near- or total eradication of preventable diseases like polio, measles, and smallpox. In the US and many other ‘first world’ nations, meanwhile, we’ve seen the legalization of abortion, oral contraceptives, gay marriage, and assisted suicide; the decriminalization of marijuana and other drugs; the destigmatization of therapy; and the increasing acceptance of (and passing of legal protections for) transgender folks. Drumpf and his supporters (and the equivalent reactionary right-wing movements in around the world) show that we still have a long way to go, but assuming we don’t all die in a ball of nuclear fire, or melt the planet with unchecked global warming, I think we’re going to get there eventually.

I honestly believe that cultural studies, and the critical theories it is built on (which in turn, are, yes, largely built on the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who were in turn influenced by Hegel, and so and so forth), has a big role to play in keeping things moving forward. As James Bohman argues:

Perhaps one of the more pernicious forms of ideology now is embodied in the appeal of the claim that there are no alternatives to present institutions. In this age of diminishing expectations, one important role that remains for the social scientifically informed, and normatively oriented democratic critic is to offer novel alternatives and creative possibilities in place of the defeatist claim that we are at the end of history. That would not only mean the end of inquiry, but also the end of democracy.

In short, critical theory provides a secular argument for pushing back against people (academic or otherwise) who would have us go back to the Dark Ages. From the perspective of the present it’s easy to forget that the Enlightenment grew out of not only a certain way of looking at the world (one that represented a fundamental break with Christian orthodoxy in favor of heterodox, and often conflicting points of view) but also, as Aaron Hanlon and others scholars of the period argue, specific historical and social conditions. It may have been built on classical Greek and Roman philosophy (and, in a far less acknowledged way, Arab-Indian math) but its best thinkers were able to go beyond these rudimentary theories of knowledge, capitalizing on the unique historical and social conditions (for example, the discovery of North America, and the global population boom fueled by New World crops) to come up with new, and far more accurate ways of not only modeling the physical world, but also emancipating our bodies, our minds, and our societies. That’s what I think critical theory is about, ultimately — continuing the project of the Enlightenment to emancipate everyone, not just upper-class men of European-descent.

To give just a few examples of people who are fighting the good fight on this front against the Petersons and Pinkers, I think it’s exciting to see way post-ac folks like Natalie Wynn (aka ContraPoints) and Oliver Thorn (aka PhilosophyTube) have been building a pro-intellectual platform for the left on YouTube, a site which unfortunately often seems to be overrun with willfully ignorant or intentionally deceptive vloggers. Other people to check out doing work in a similar vein would be Mike Rugnetta and the (sadly now defunct) PBS Idea Channel, and Matthew Wrather and the gang over at the Overthinking It Podcast.

Finally, I think it’s important to point out two more things:

The first is that I wouldn’t be going back to grad school at all without the support of my brilliant PhD advisor and critical theory-ninja Heather Inwood, who studies and teaches contemporary Chinese literature and visual culture (particularly online permutations thereof) in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge (just a hop skip and a jump up from London by train). Thanks to that initial vote of confidence from Professor Inwood (and also sitting in on some very awesome courses taught by Adam Chau and Hans van de Ven) I’ve been able to spend the last couple of months reading and discussing a ridiculous number of books that I didn’t think I’d ever really ‘get’ (Here’s looking at you, Foucault) with some of the smartest, driven people I’ve ever met. It’s been pretty humbling.

Secondly, if I hadn’t been able to secure a generous three-year PhD scholarship, I wouldn’t have been able to go back to school in the first place. I was fortunate enough to get through my BA with minimal debt, thanks to my parents (plus scholarships, working, and living at home). I lucked out again with a scholarship for my MA (see ‘next-level wizard’ Rea), in addition to the already mentioned insanely understanding and supportive spouse. If I had had to rely on loans for my previous two degrees, I could very easily have over six figures of debt right now. Without a scholarship for my third, I would probably be looking at doubling that. (And that’s assuming I could even get a loan at all!)

I personally believe that education is a right, rather than a privilege. Even so, that doesn’t negate the enormous amount of privilege I’ve lucked into throughout my life. I do hope that in some small way by continuing to post online, in addition to my work as an educator and scholar, I can do a little to pay back that debt of privilege and encourage other folks who are interested in the things I’m interested in to walk in the direction of the light, rather than the dark.