Recently, I have been working on a few projects to get Chinese comics published in English translation. It’s a tricky proposition, given the limited “brand name recognition” for manhua outside of China, in comparison to the much better known (and therefore more marketable) Japanese manga.

Comicsfans

Jade Dynasty, Jonesky, Culturecom, AniTime, and RightMan

Special Comix

There also is a lively indie comics scene which has put out several large collections over the past decade, the most active of which (until recently) was Special Comix SC 漫畫. Co-founded by a group of independent artists in Nanjing who were influenced by experimental European, Japanese, and North American comics, Special Comix put out five massive 500+ page anthologies between 2006 and 2012. In May, 2010, they partnered with the Swiss underground comix magazine Strapazin, which apparently was attracted to the fact that Chinese comics are relatively unknown in Europe, and that Chinese artists are subject to (more obvious at least) political oppression. That same year, the third Special Comix anthology picked up an award at the Angoulême International Comics Festival. Since putting out their last anthology back in 2012, however, the group seems to have by and large disbanded. Part of the reason may be due to fact that none of their books have GAPP approved Chinese IBSN numbers, so technically they were breaking the law when they self-published them. That doesn’t explain why they are still available on Taobao, though.

Page from Birdman by Storyof 胡晓江 from Strapazin Issue #100, May, 2010

Comix Home Base

Meanwhile, throughout the Sinosphere, governments are stepping in to give domestic comics and animation official recognition for the role they play in creating jobs in the creative sector. In 2013, the Comix Home Base 動漫基地 was established Wanchai, as partnership between the Hong Kong Comics and Animation Federation, the Hong Kong Arts Centre, and the Urban Renewal Authority (URA). With over $200 million HKD [~26 mil USD] in the project in 2013, Comix Home Base represents a significant effort on the part of the Hong Kong government to support the comic and animation industry. The Hong Kong Comics and Animation Federation also received ~2 million HKD (300,000 USD) in funding from CreateHK in 2013 to bring the International Comic Artists Forum 國際漫畫家大會 to Hong Kong that year.

Comix Home Base 動漫基地, a four-story heritage building in the Wanchai district of Hong Kong that has been converted into studios, commercial office space, and a gallery to promote Hong Kong comics and animation

Comic and Animation Museum of China

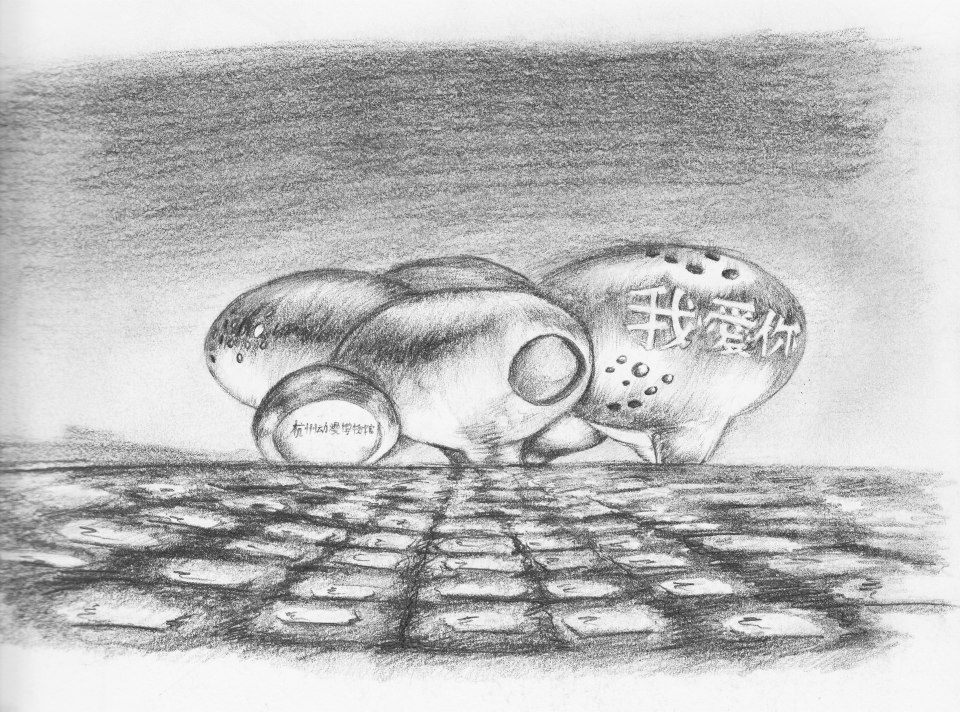

Not to be outdone meanwhile, the PRC government is investing 100 million USD to build the Comic and Animation Museum of China 中國動漫博物館 in Hangzhou, just to the south of Shanghai, which already has it’s own Comic and Animation Museum 上海動漫博物館. Interestingly, while the mockup video produced by the architectural firm that won the design competition for the building (which according to their website is supposed to look like 3D speech bubbles) features statues of well-known characters from Pokemon, Dragonball, Gundam, and Kung-fu Panda, I was only able to catch a smattering of images on the walls from Chinese cartoons such as Pigsy Eats Watermelon 豬八戒吃西瓜, a famous paper-cut animation produced by Wan Guchan 萬古蟾 and his twin brother, Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴 at the Shanghai Animation Studio 上海美術電影製片廠 in 1958, the Little Orphan Three Hairs aka San Mao 三毛 cartoon from the 1980s, or the much more recent animated television series Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf 喜羊羊與灰太狼. Although the original design by MRDV seems to have been changed significantly (likely to save money), the concept drawings are still pretty freaking cool to look at.

Drawing of the Comic and Animation Museum of China by Peihui as originally conceived

The future of Chinese comics and animation

While it remains to be seen what the outcome of all this investment will be, my personal hope for the industry lies not with government subsidies for multimillion dollar buildings, but with individual creators who are finding a way to make a living from comics and cartooning. While not yet great in number, some artists like Kong Khong-chang 江康泉, aka Kongkee 江記, and Chi Hoi 智海 are finding ways to make both commercial and experimental comics, while also monetizing their creations through merchandising deals and books. I’m also excited to see Chinese artists coming to comics after studying abroad, for example the NYC-based illustrator Yao Xiao, who had her great autobio comic “Memoir of a Part-time Knight” featured in the Chainmetal Bikini comics anthology or the Berkeley-based Yan Wenqing, aka Yuumei Fisheye Placebo, who does awesome illustrations that comment on the effects of pollution and global warming on the natural world, in addition to her recently launched line of cat-ear headphones.

“Drawing comics with cats & listening to old 1930s Chinese Jazz” by Yao Xiao

Rather than seeing the internet as simply a source of piracy, these artists are actively engaging in social networks to build up a niche fan base to not only support their work, but also to raise awareness of Chinese comics and cartooning. Although manhua may never be as well-known as manga, I think there is an enormous potential for future growth in this field if a concentrated effort is made to put translated Chinese comics into the hands of comic book fans.

- Taiwan is another area that deserves further study, although my preliminary research suggests that the Taiwanese market is more heavily influenced by Japanese comics than either the PRC or Hong Kong. [↩]

- One exception to this is the work of Huang Jiawei 黃嘉偉 (b. 1983), whose debut comic Ya San 伢三 caught the attention of fan of artists like Masamune Shirow and Brandon Graham. His more recent book Zaya, co-written with JD Morvan, was published in English by Magnetic Press in September, 2014. [↩]

- Organized by Tung Tak Enterprise Ltd. [↩]

- Current owner of the rights to Tony Wong’s work at Jademan. [↩]