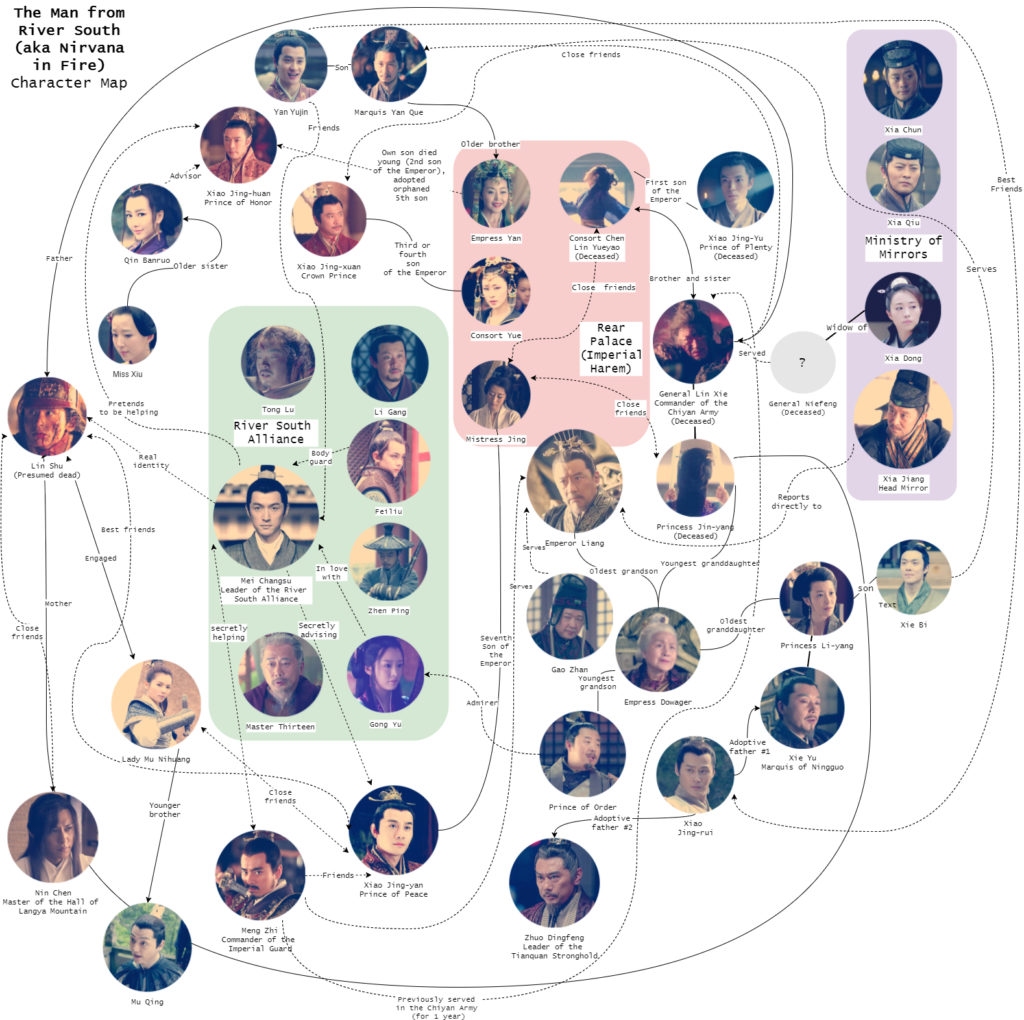

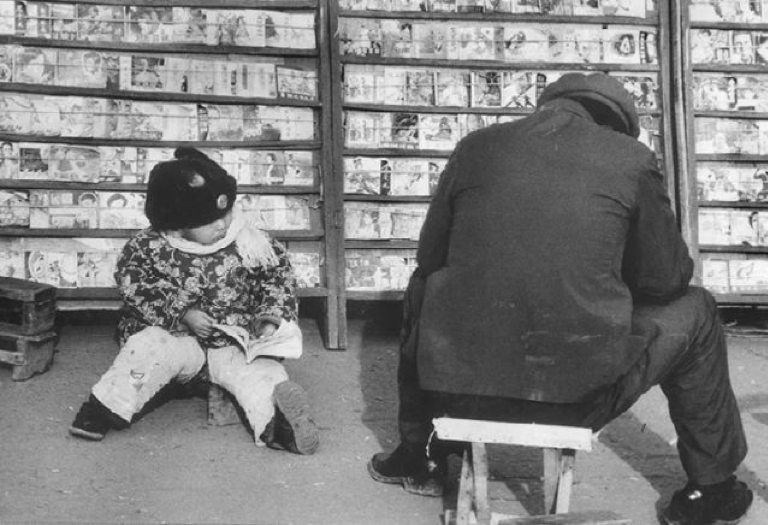

I haven’t posted much on here over the past year that I’ve been at Cambridge, and in part that’s because my work (as with most first year PhDs I think) has been pretty scattered. I’ve been reading a lot, and writing a lot, but very little of what I’ve written seems particularly blog-able. I do want to share some of the stuff I’ve come across in my research into lianhuanhua 连环画 however, and also give a quick summary of where I see my work going from here. As it happens, last week I was at the Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing sharing a very brief version of just that on a very fun panel with comrades-in-arms and fellow graduate students Shan Xiaodan, Lyu Guangzhao, and Peng Qiao. I’ve done a quick write-up of the conference , which you can read here. What follows is an expanded version of that presentation, with a brief example drawn from two of my case studies.

The question that I’ve come to over various revisions of my project is this:

How can we, from the perspective of the present, make post-Mao lianhuanhua [comic books] intelligible?

I’m using here something that Jonathan Culler once said about the work of Roland Barthes: “The critic’s job, Barthes argues, is not to discover the secret meaning of a work – the truth of the past – but to construct intelligibility for our own time [l’intelligible de notre temps].”1 Part of what I’ve been struggling with in my work is getting away from the idea that there is some sort of hidden message in the lianhuanhua that I’ve been looking at.

The working title for my thesis has also gone through several revisions, but for the moment I’ve settled on “Low Culture Fever: Chinese Comics After Mao, 1976-1983”.

As, you may have notices, I’ve referred to lianhuanhua as both “comics” and “comic books”. It’s intentional, even if it is a bit of a controversial point. I’ve also played around with adding the words, “Anxiety and Ambition in” before “Chinese Comics”. This was part of a previous revision which brought in affect theory to try to think my way out of an ideological corner I’d painted myself into. I’m still planning on using affect theory quite a bit, but after my last meeting with my committee, I’ve been rethinking how much I want to make that approach really front and center in my thesis, and how much I want to provide some alternative theoretical frameworks of my own invention.

But the real sticking point for the moment in my terminology is whether or not lianhuanhua are “comics” or “comic books”.

Continue reading- Jonathan Culler, Barthes (Fontana Paperbacks, 1983): 17; Roland Barthes, Critique et Vérité [Criticism and Truth] (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1966), trans. Katrine Pilcher Keuneman (The Athlone Press, 1987): 260. [↩]