Seeing that Eric Abrahamsen’s translation of Xu Zechen’s Running Through Beijing was released by Two Lines Press earlier this month, it seems appropriate to sketch out a tradition of movie pirating that existed in mainland China before the advent of bootlegged DVDs:

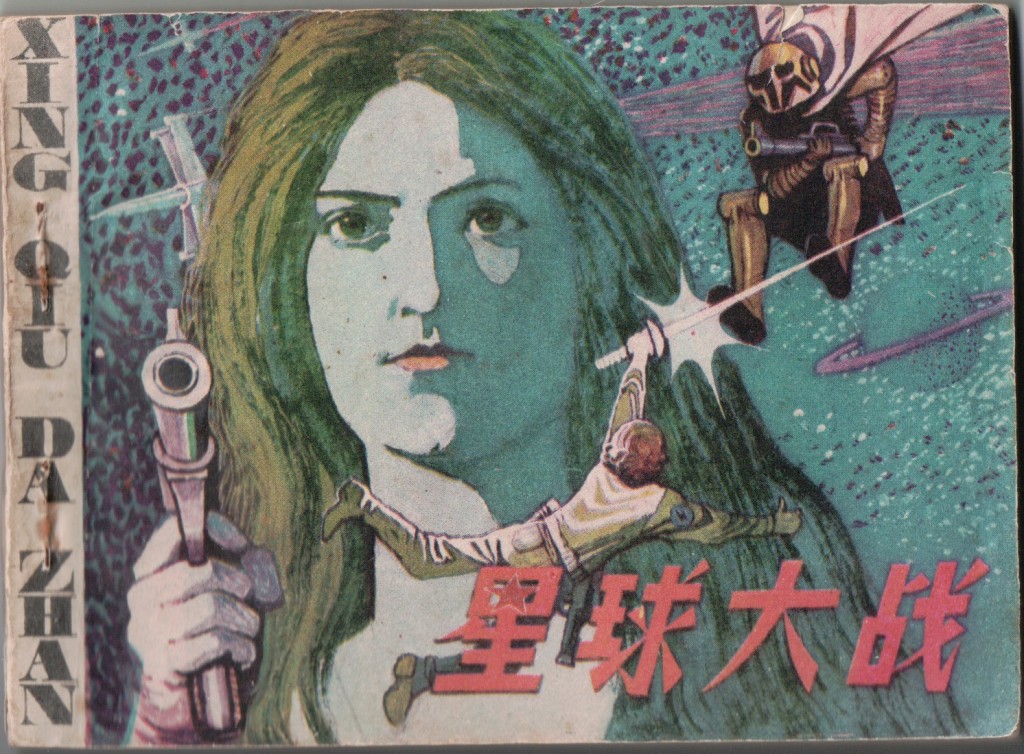

This is a lianhuanhua 連環畫 adaptation of Star Wars which historian Maggie Greene picked up at the infamous Wen Miao 文廟 book market in Shanghai in 2011. She recently posted a complete scan to her blog The Wayward Historian, which Brendan O’Kane OCRed and reposted here. According the copyright (sic) page, this work was published in December, 1980, by Yuebei Press 粵北印刷廠 and distributed by the Guangdong branch of the state-owned Xinhua Bookstore 廣東省新華書店, with editing by Zhou Jinzhuo 周金灼 and illustrations by Song Feideng 宋飛等.

Lianhuanhua, or “linked picture books,” have been around since roughly the turn of the 20th century, when cheap printing technology made it possible for publishers to mass produce high fidelity images and text at low cost, providing a new form of entertainment for growing numbers of literate urbanites.1 As comics historian Paul Gravett described them in a 2008 interview for the Manhua! China Comics Now Exhibition2 (appropriately introducing an unauthorized 1984 lianhuanhua adaption of Hergé’s The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus ):3

What I’m going to show you here, this is actually what Chinese comics came from. Chinese comics, before they were called manhua they were called lianhuanhua, which means, basically, the hua means drawings and the lianhuan means linked up, joined together in a chain. So it’s like, comics in sequence, or drawings in sequence. And they appeared in color, and in black and white, particularly in this format and also in larger format books, with one image per page, often with the text appearing underneath. But interestingly, they did actually use speech balloons as well. As we see here there are examples of it. And they were cheap; even if you couldn’t afford them you could actually sit in the street and rent them. Literally, you’d read them in the street, there’d be some chairs, there’d be a guy with a whole shelf loan of these little tiny comics, and you could read them. Because of course some of these comics run for several volumes, maybe, ten, twenty, thirty volumes, and you could read them all in one sitting, just like manga cafes now. Just like the way manga’s gone now—that was already going on back in the twenty and thirties.4

Although it is somewhat misleading to say that lianhuanhua proceeded manhua, as both emerged more or less contemporaneously as distinct forms of production, Gravett correctly points out that it wasn’t until the 1920s and 30s that lianhuanhua really took off, and that for most of its history lianhuanhua was something that you would rent rather than own. Due to their inherent disposability relatively few of the earliest lianhuanhua have survived. That said, one which did seems to indicate that the tradition of adapting American movies to lianhuanhua is older than we might think:

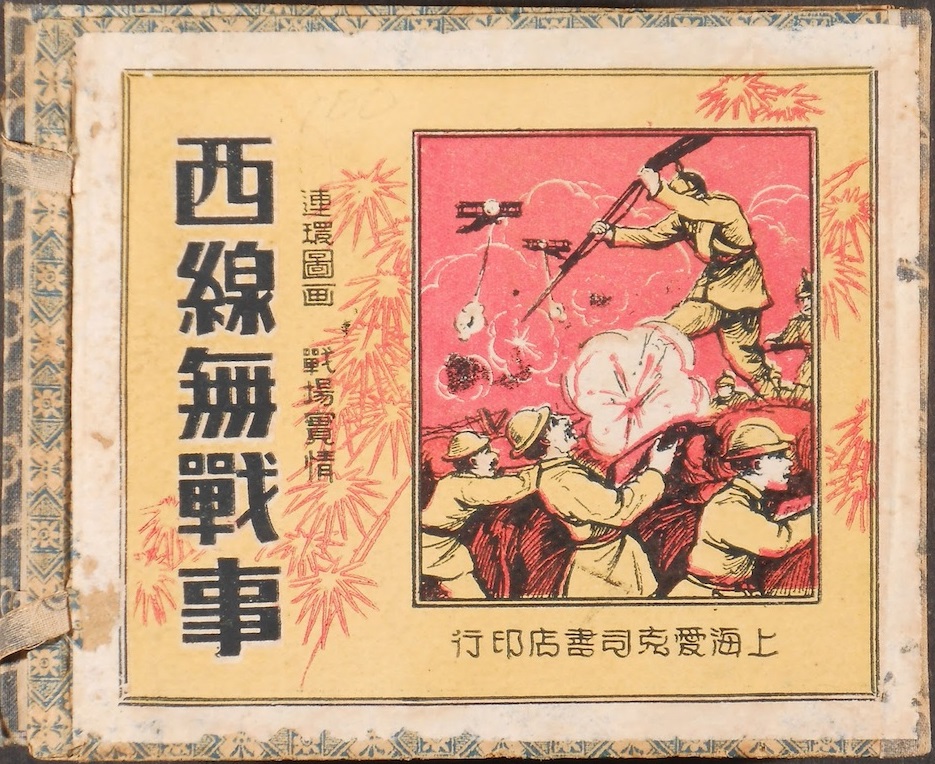

All Quiet on the Western Front 西线无战事 published in the 1930s by Shanghai Aikesi Bookstore 上海爱克司书店, adapted from the original, translator and artist unknown.

This is a lianhuanhua adaptation of WWI veteran Erich Maria Remarque’s bestselling novel Im Westen nichts Neues, first serialized in 1928 and later translated into English by Arthur Wesley Wheen in 1929 as All Quiet on the Western Front. Presumed to pirated, this adaptation appears to have been based on the 1930 American film version directed by Lewis Milestone which was released in China only to be banned along with all other “anti-war” films by the Nationalist government in 1934.5 Curators at the Rauner Library Special Collections at Dartmouth which purchased the adaption in 2013 have pointed out that although antiwar films were banned in China, versions of the story continued to circulate in Shanghai as a form of “cultural resistance.” Moreover, despite reports which indicate that attendance for anti-war films such as All Quiet on the Western Front was poor,6 the existence of this work shows that its anti-war message must have held some appeal.7

Like manhua, lianhuanhua production seems to have mostly died out during the Second Sino-Japanese War due to shortages in paper and ink following the Japanese occupation and the partial destruction of Shanghai, home to the vast majority of Chinese printers, presses, and publishers. Following the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War of 1945-1949, however, lianhuanhua experienced a second golden age as part of the general push for mass literature for the proletariat, with Mao Zedong and other leaders promoting “new” lianhuanhua as propaganda for the semi-literate farming communities of the Chinese countryside as well as the less numerous educated masses in the cities. As Mao reputedly said in 1950, “Lianhuanhua is read by children as well as adults, illiterates as well as educated. Why not set up a publishing house to issue a series of new lianhuanhua?”8 As had been the case with the earlier lianhuanhua, the majority of these works were retellings of classical operas such as The Red-Maned Steed 紅鬃烈馬, Mulan Joins the Army 木蘭從軍, The Romance of the Western Chamber 西廂記, etc, with relatively minor editorial changes to emphasize class struggle.9 Some of the more explicitly political works produced however, include an adaptation of the Irish socialist revolutionary Ethel Lilian Voynich’s novel The Gadfly and Russian Nikolai Ostrovsky’s socialist realist novel How the Steel Was Tempered, both of which were also made into films in the Soviet Union around the same time:

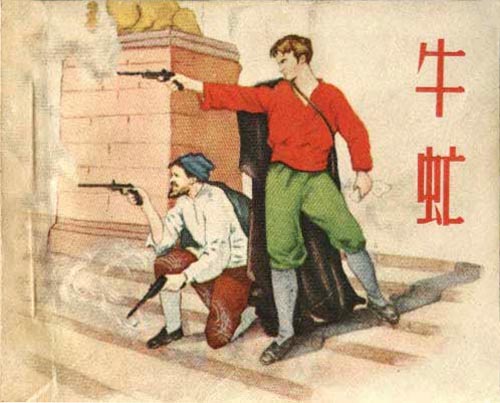

The Gadfly 牛虻, published in 1955 by New Art Press 新美术出版社 with art by Lu Yanshao 陸儼少 (1909-1993), editor unknown.

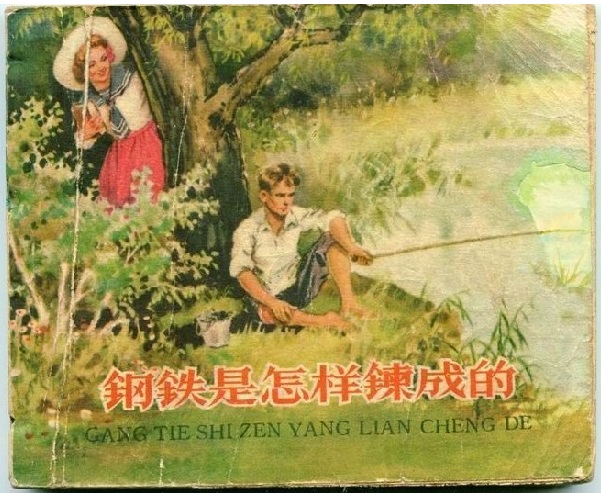

How the Steel Was Tempered 鋼鐵是怎樣煉成的, published in 1959 by The People’s Fine Arts Press 人民美術出版社, adapted from the original novel by Wang Su 王素with art by Yi Jin 毅進.

It also seems relevant to mention that lianhuanhua were apparently made available for free to passengers on trains to help them pass the time, not unlike in-flight movies today. In the introduction to a collection of translated lianhuanhua the journalist Gino Nebiolo describes reading lianhuanhua like these on a train between Hangzhou and Shanghai during a state-sponsored tour in the late 1950s10:

I observed my companions—workers, petty officials, and peasants. The train was moving slowly, at a speed well under the conventional forty miles an hour, and the heating system was out of order. Only two women and one old man laid aside their comic books and fell asleep. Among the others, no one paid attention to the cold or to the repeated stops; they were all completely absorbed in their reading. And if one of them finished his comic book before the others, he looked around him with restrained impatience, and then, when he got the next one, plunged into it without delay. Several times the stewardess came into the compartment with more hot water for tea, but no one noticed, and the conductor had to knock his ticket puncher against the metal rim of the baggage rack, as if to arouse sleepers, in order to get any attention. At dawn, just a few minutes before arrival at the central station of Shanghai, one of the passengers collected the comics, smoothed frayed corners, and turned them over to the stewardess, who wrapped them in a plastic case.11

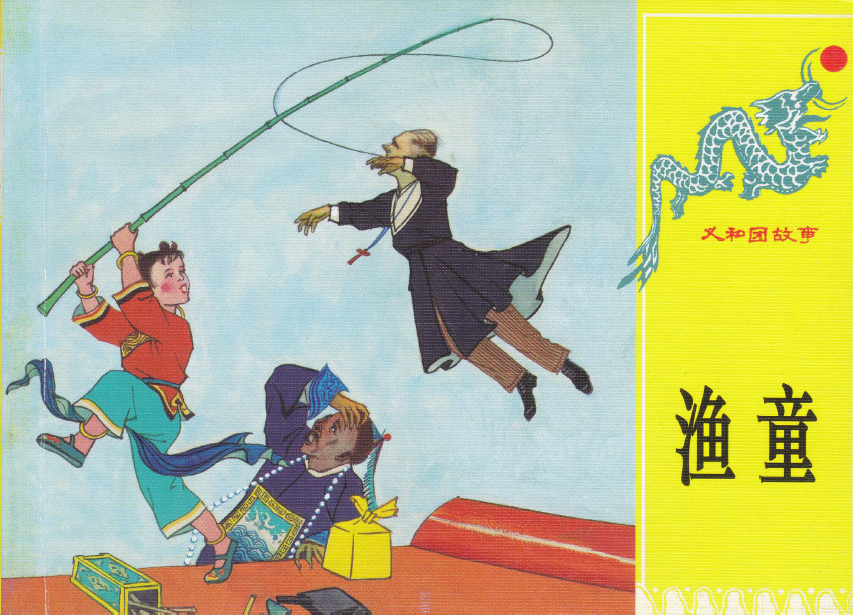

Despite the Anti-Rightist Movement 反右運動 of 1957-1959 targeting prominent lianhuanhua artists such as Hua Sanchuan 華三川 (1930-2004),12 and the break with the Soviet Union effectively ending the flow of post-Stalin Russian and Eastern Bloc literature and film into China,13 lianhuanhua continued to flourish during the (relative) cultural thaw of the early 1960s. Perhaps in response to the political developments, the proportion of overtly political (not to mention xenophobic) works seem to have increased however. For example, two separate series of lianhuanhua adaptions of stories collected from survivors of the Boxer uprising in rural Shandong by the writer and folklorist Zhang Shijie 张士杰 (1931-1978) were published in the late 1950s and early 1960s: the fifteen volume series Boxer Stories义和团故事 by the People’s Fine Art Publishing House 人民美术出版社 in Beijing between July 1959 and April 1960, reprinted 2012; and the fourteen volume series Boxer Legends义和团传说故事 by the Tianjin Fine Arts Publishing House between May 1959 and November 1963, reprinted 2001. These stories include a surprising amount of fantastic elements: in Hong Dahai 洪大海the titular Boxer is driven to the brink of defeat only to grow to enormous proportions and defeat an entire army of foreign devils single-handed by drowning them in his spit, while in Fisher Boy 鱼童14 a wizened fisherman discovers a small child inside a lotus blossom who makes gold beans and fishes for conniving priests in cahoots with the local yamen:

Fisher Boy 渔童, published in 1959 by The People’s Fine Arts Press, adapted from Zhang Shijie’s original (collected) story by Wu Chao 吴超, Cheng Hua 程华, and Bo Chen 伯诚 with art by Guang Yu 光玉and Da Fang 达方.

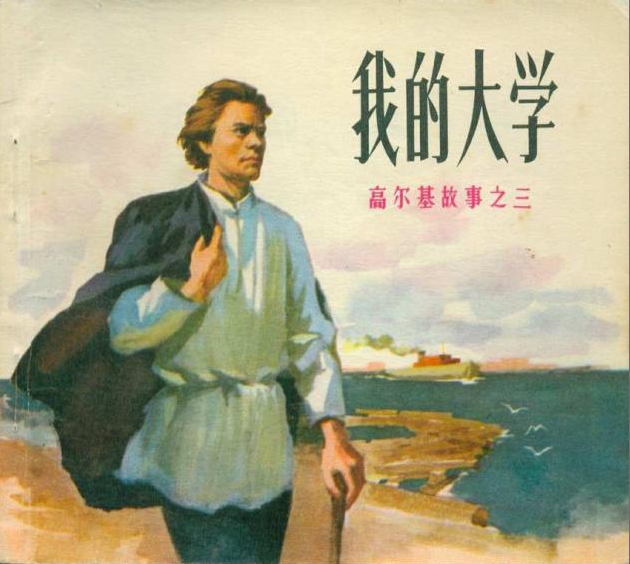

With the advent of the Socialist Education Movement in 1963 and the much larger Cultural Revolution in 1966 however, lianhuanhua stagnated again until 1970, when Zhou Enlai began promoting lianhuanhua as an effective tool for propaganda.15 Adaptions of Jiang Qing’s model operas 樣板戲 were produced in large quantities, including Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy 智取威虎山, Shajiabang 沙家浜, etc. Interestingly, several biographies of early Soviet leaders and intellectuals such as Lenin and Maxim Gorky were published in the early 1970s:

My University: Volume Three of the Biography of [Maxim] Gorky 我的大学: 高二其故事之三 published in 1972 by The People’s Fine Arts Press, adapted from the original with art by Dong Hongyuan 董洪元.

With the death of Chairman Mao in 1976 and the fall of the Gang of Four shortly thereafter, one would like to think that the eventual renaissance in lianhuanhua which followed was sudden and immediate. It was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, that the political situation in China became relaxed enough to allow the reprinting of many of the earlier lianhuanhua adaptions of traditional operas. At least two lianhuanhua went so far as to address the political turmoil of the Cultural Revolution directly, the first being a 1978 adaptation of Lu Xinhua’s盧新華Scar傷痕by Chen Yiming 陈宜明, Liu Yulian 刘宇廉and Li Bin 李斌and the second being the 1979 adaption of Zheng Yi’s鄭義novel Maple楓by the same authors, both of which were published to some controversy in Lianhuanhua Pictorial 连环画报.16 Many other lianhuanhua dealt with the Gang of Four allegorically: in the 1977 work Evil-Hearted Empress Lü野心家吕后 published by The People’s Fine Arts Press, the malevolent Empress Lü Zhi呂雉皇后(241–180 BC) who usurped the throne from her son, Emperor Hui漢惠帝, is clearly meant to be equated with Jiang Qing, making explicit reference to her and the Gang of Four in the introduction.

At the same time as this was going on, other lianhuanhua artists began turning their attention to American movies and TV shows:

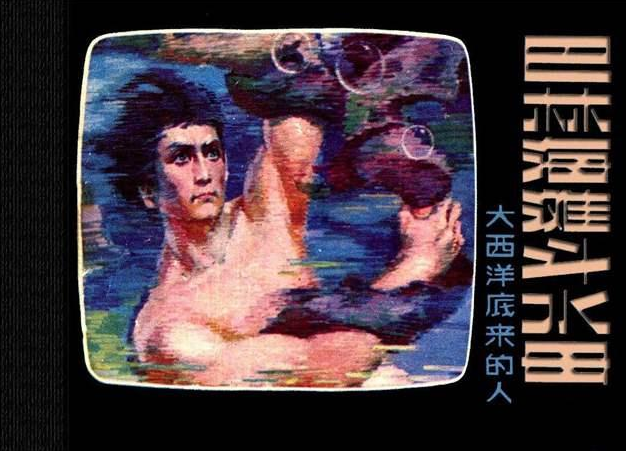

Fighting Jellyfish on the Bahrain Beach (?): The Man from the Bottom of the Atlantic 巴林海灘鬥水母–大西洋底來的人 published in 1983 by Liaoning Fine Arts Press 遼寧美術出版社, adapted from the original television show by Yu Xiang 魚翔 with art by Xu Xilin 徐錫林.

Above we have an adaption of the first American television show to be shown in the PRC. Although it is almost entirely forgotten in the US, many Chinese who grew up during the 1980s still remember The Man from Atlantis with fondness.17 Other works include the aforementioned Star Wars and Tintin adaptions, as well as eighties ephemera such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Transformers, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and He Man:

Author and publisher unknown, 1980s.

Also, lest we think only American works were targeted:

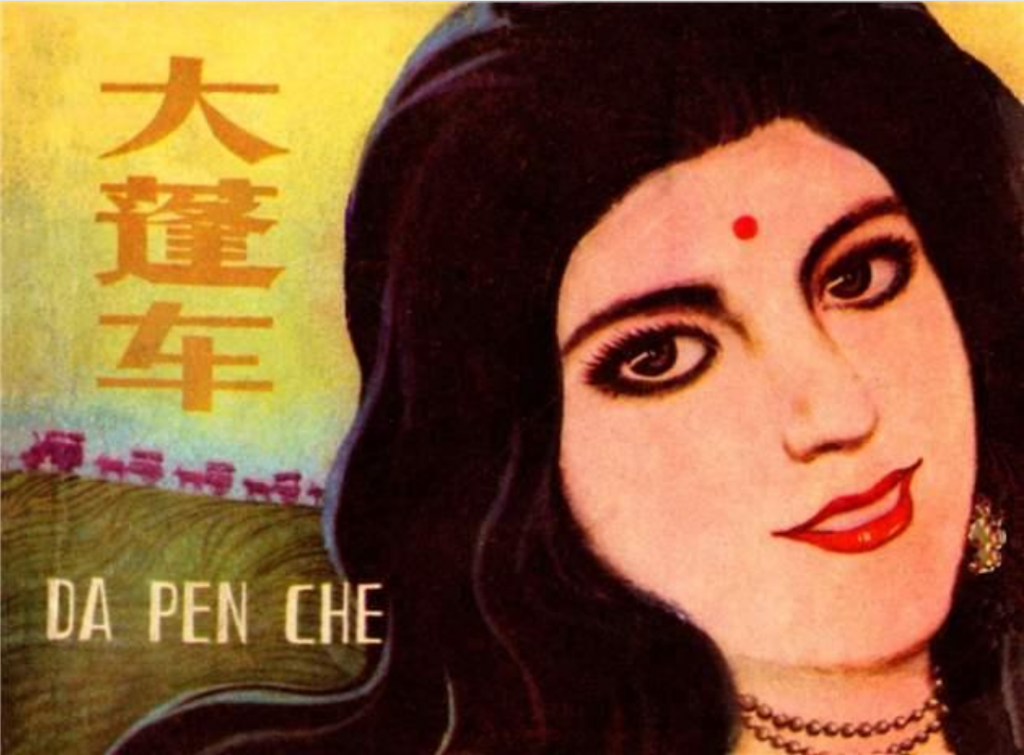

Caravan 大蓬車, published November, 1981 by the Fujian branch of the Xinhua Bookstore 福建省新華書店, adapted from the 1971 Bollywood film by the same name by Chen Qinchun 陳勤群 and Mao Zhiyun 茅志雲 with art by Yang Tuanjun 旸團君 and Mao Zhiyun 茅志雲. The original film was directed by Nasir Hussain, with a translation from the Hindi being released in mainland China in 1980 by the Shanghai Film Translation Studio 上海電影譯制廠.

Today, lianhuanhua is essentially a moribund medium, with most interest in the work coming from collectors and nostalgic adults. Most young people are quickly turned off by the overt political messages in the works produced in the 1960s and 1970s, and find little to enjoy in the adaptions of traditional operas from the 1950s and earlier. For cultural historians of modern China, however, lianhuanhua represent a treasure trove of information about the way people lived and the things that they cared about. I think it would be exciting to explore the ways lianhuanhua could be used in classrooms to liven up language textbooks, or explore the way historical events such as the Sino-Russian split or the Cultural Revolution were represented in the popular media of the day.

- For a history of the medium, see Shen, Kuiyi. “Lianhuanhua and Manhua – Picture Books and Comics in Old Shanghai.” In Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books, edited by John A. Lent, 100–. University of Hawaii Press, 2001. [↩]

- This exhibition ran twice, first at the London College of Communication from March 7 to April 11, 2008, and then again the next year at Durham Oriental Museum from May 2 to September 27, 2009, and included over 200 examples of Chinese comics and cartoons. [↩]

- Hergé [埃爾熱], Lan Lianhua – Ding Ding Lixian Ji (Shang)藍 蓮花—丁丁歷險記 (上) [The Blue Lotus – The Adventures of Tintin (Vol 1 of 2)], trans. by Binggang Li [李秉剛] (Beijing: Zhongguo Wenlian Chubanshe, 1984), Beijing; Hergé [埃爾熱], Lan Lianhua – Ding Ding Lixian Ji (Xia)藍 蓮花—丁丁歷險記 (下) [The Blue Lotus – The Adventures of Tintin (Vol 2 of 2)], trans. by Binggang Li [李秉剛] (Beijing: Zhongguo Wenlian Chubanshe, 1984), Beijing. [↩]

- Alex Fitch / Paul Gravett, Panel Borders: Manhua! China Comics Now Part 1, 2008 <http://archive.org/details/PanelBordersManhuaChinaComicsNowPart1> accessed 16 April 2014 [↩]

- Zhu, Ying, and Stanley Rosen, eds. Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema. Hong Kong University Press, 2010, 66 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Rebecca Onion also draws this connection in her short article on Slate “All Quiet on the Western Front: The Book Translated into Chinese Lianhuanhua.”, which I found via the China Books blog post “Chinese Graphic Novels or ‘Lianhuanhua’ « China Books,” both accessed May 23, 2014. [↩]

- Pan, Lingling. “Post-Liberation History of China’s Lianhuanhua (Pictorial Books).” International Journal of Comic Art 10, no. 2 (October 15, 2008): 694–717, 702. [↩]

- For examples see http://digicoll.manoa.hawaii.edu/storybook/Pages/browseby.php?s=browse&by=year [↩]

- http://www.provincia.asti.it/hosting/moncalvo/boll7htm/gino.htm [↩]

- “Introduction,” vii, Frances Frenaye trans. from The People’s Comic Book; Red Women’s Detachment, Hot on the Trail and Other Chinese Comics. Endymion Wilkinson trans. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Press, 1973 [↩]

- Pan, Lingling. “Post-Liberation History of China’s Lianhuanhua (Pictorial Books),” 704. [↩]

- One can only imagine, for example, that if the works of Andrei Tarkovsky and Stanislaw Lem had been available that China might have a few more science fiction authors today. [↩]

- This story was later made into a celebrated animated using paper cutouts, directed by Wan Guchan 萬古蟾 and produced at the Shanghai Animation Studio 上海美術電影製片廠 in 1959. [↩]

- Pan, Lingling. “Post-Liberation History of China’s Lianhuanhua (Pictorial Books),” 705. [↩]

- See 栗宪庭. “现代迷信的沉痛教训——谈连环画《枫》对典型环境的刻划.”美术 no. 08 (1979): 37–38. [↩]

- The cartoonist Nie Jun 聂峻, for example, references the show throughout his illustrated memoir Searching for the Sea 找海 (Jiangsu Fine Arts Press江蘇美術出版社, 2006). [↩]

Pingback: A Long Time Ago in a China Far, Far Away … | Maggie Greene

Pingback: Chinese Lianhuanhua: A Century of Pirated Movies – Nick Stember | CleverJots

Pingback: Chinese Star Wars Comic (Part 1 of 6) | Nick Stember

Pingback: Scoperto un adattamento cinese a fumetti di Star Wars risalente agli anni ottanta! | Il blog di ScreenWeek.it

Pingback: Scoperto un adattamento cinese a fumetti di Star Wars risalente agli anni ottanta! | cine-mania aggregatorcine-mania aggregator

Pingback: Scoperto un adattamento cinese a fumetti di Star Wars risalente agli anni ottanta! | Blog di condivideregratis

Pingback: Lianhuanhua, los cómics chinos | EsAsia

Pingback: Nerdcore › Vintage Star Wars Lianhuanhua from China

Pingback: Giving pleasure, not a political lesson | Maggie Greene

Pingback: This Chinese Comic Bootleg of Star Wars is Full of Droid Kissing and Booze | Your Mini Con

Pingback: “Lianhuanhua”, los librillos ilustrados del entretenimiento y la propaganda en la China comunista – Historias de China