The Vancouver International Film Festival is town again and all I can say is, man, time flies. While much of my work to date has focused on Chinese comics, I’ve been trying to find a natural way to transition to a broader focus that encompasses my interests in Chinese literature and film.

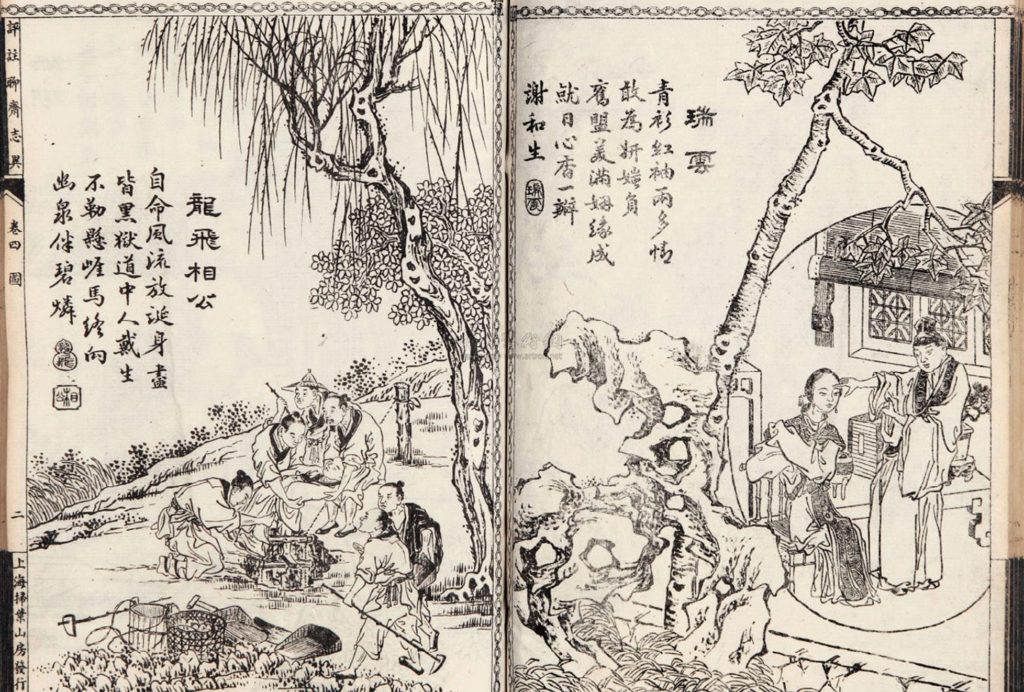

Page from an illustrated edition of Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, late Qing.

Part of the problem has been trying to find books and movies that really excite me, and part of that problem has been putting into words what I’m actually looking for. The best I’ve come up with is ‘sino-weird’—last year I even set up a Tumblr under that name. During my undergrad years, I really got a kick out of reading Chinese ghost stories like “The Biography of Miss Ren” 任氏傳 from Chen Han’s 陳翰 A Collection of Strange Events 異聞記 and true crime tales like Feng Menglong’s 馮夢龍 “The Case of the Dead Infant” 況太守路斷死孩兒.1 After being suppressed during the Cultural Revolution, tales of the bizarre and macabre have seen something of a comeback in mainland China over the last couple of decades, Gordon Chan’s 2008 film Painted Skin 畫皮 and the 2012 sequel (directed by Wu Ershan) being two recent examples. In Hong Kong of course, there is the much earlier success of Tsui Hark’s 1987 film A Chinese Ghost Story 倩女幽魂 , which like Painted Skin, was loosely based on a short story from Pu Songling’s collection of classic ghost stories Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異.

Following my interest in the supernatural side of the Middle Kingdom, on Monday I had the pleasure of getting to see Yang Chao’s 杨超 latest film Crosscurrent 長江圖, which was followed by a Q&A session with the director, moderated by Shelly Kraicer. While there are probably some obvious comparisons to be made to films like Jia Zhangke’s Still Life 三峡好人 (2008) and Yung Chang’s Up the Yangtze (2007), Crosscurrent is concerned with more than simply documenting a historical moment. In fact, there is something almost ahistorical or even anti-historical about the film–the only references to place the film in a historical chronology that I can recall are a mention of the year 1989 in a poem, images of the Three Gorges Dam, documentary footage of river tracers, and the narrator mentioning passenger ferries stopped providing service on the river the year previous.

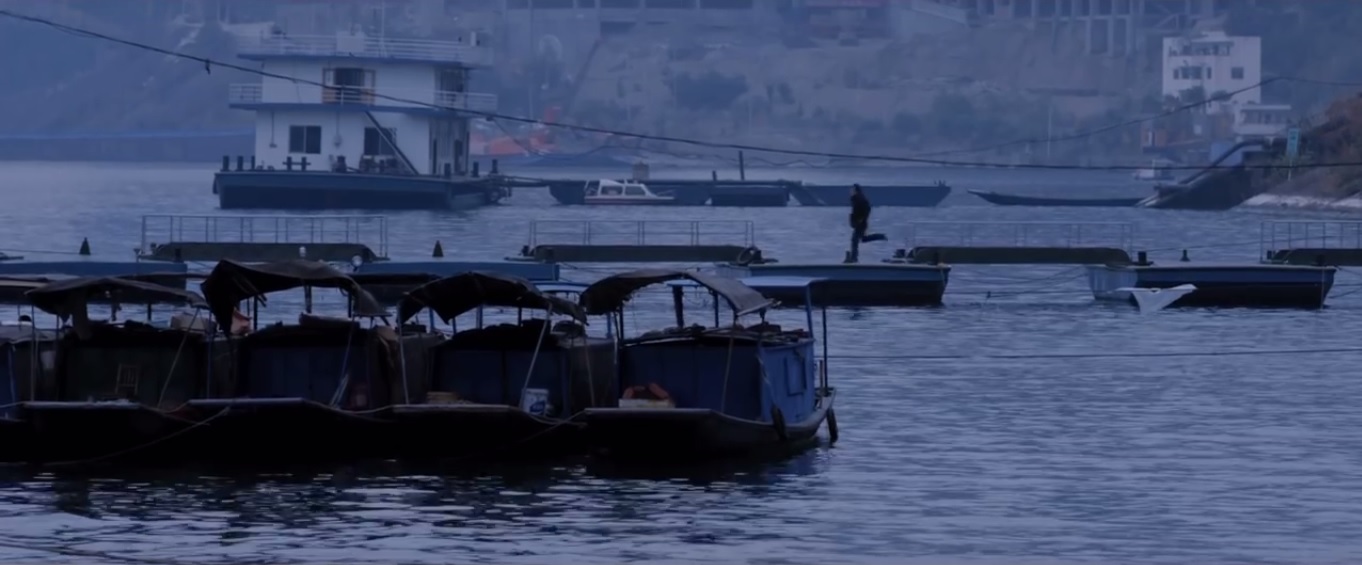

Gao Chun searches for An Lu in Crosscurrent.

The film follows a busted-down barge filled with mysterious cargo of ‘little fish’ as it makes its way from Shanghai to an unknown destination upriver. At dawn, on the banks of the Yangzte, the protagonist, Gao Chun (played by Qin Hao), catches a small black fish and places it in a golden urn before a bonfire—an offering to meant to appease the restless soul of his recently deceased father. Returning to his ship, he catches sight of a young woman on old-fashioned wooden boat. When he runs into her again at the next town up the river, they fall into bed, undressing each other like an old married couple. It’s not clear if it’s an act of (albeit restrained) passion, or a business transaction, but they whatever the case, Gao Chun and An Lu (Xin Zhilei) find themselves reunited again and again at each stop along the river, guided by an unusual framing device: a book of poems. Found in a dusty box under the ship’s engine, the poems (written by the director) convey a vague sense of loss. Visually stunning, the film itself meanwhile, conveys a strong undercurrent of Buddhist detachment as the natural beauty of the river is juxtaposed with the ugly decay of rusting hulks and rotten river towns.2

As the movie progresses the Buddhist themes become more pronounced, with An Lu in training to become an adept. Traditional Chinese literature is full of illicit affairs between monks and nuns, so Yang Chao may have been drawing on these stories. On the other hand, it could just have well been sui generis: In the Q&A afterwards, when Yang Chao told the audience he was hoping to make a spiritual movie, as opposed to a secular or even specifically Buddhist film.

Although it’s hard to imagine two films that are more dissimilar, when An Lu is later reincarnated massive river-dolphin, it suggests a connection to Stephen Chow’s recent blockbuster mega-hit, the Mermaid, where the (super)natural is likewise corrupted by greed and progress. Yang Chao mentioned that his film was given a general release in China, appearing alongside films like Transformers—an annoying mistake for viewers who were expecting something with more explosions and less poetry. While the Mermaid has its share of zany special effects and wulitou humor every bit the equal of the latest and greatest Michael Bay extravaganza, I think there is a good argument to be made that viewers were also attracted to the environmental message of the film—the same viewers perhaps, who propelled Chai Jing’s documentary Under the Dome to viral success in 2015.

Handing over the book of poems.

At the end of Crosscurrent, Gao Chun follows the Yangtze River to its source in the mountains of Tibet, arriving at An Lu’s mother’s tombstone on a, prayer-flag strewn rocky cairn. In his interpretation of the ending, Yang Chao told the audience that he saw the Three Gorges Dam as a physical barrier which separates the Gao Chun and An Lu. After the river barge passes through one of the massive, groaning locks of the great edifice (a scene which is likewise used to memorable effect in Up the Yangtze), An Lu remains trapped on the rocky shores of the muddy river, eventually disappearing in a massive blaze—a fitting conclusion to the fire-lit consecration of the father-fish in the opening scene. This is also the point at which Gao Chun leaves his barge and the river proper behind, after being attacked by a business associate with a knife. Again, I am reminded of the random and (seemingly) gratuitous violence at the end of the Mermaid, when the female lead is butchered to save her human lover.

If An Lu embodies the river though, then what does Gao Chun represent? In the Q&A, Yang Chao joked that his movie was meant to show the superiority of Chinese women, who he sees as being stronger than Chinese men. To bring things back to the spiritual realm however, I would argue that by associating the boats and dams with men, technology and progress are presented as the ‘male’ counterpart to the ‘female’ river—the Taoist concept of (cringe) yin and yang, female and male. It’s a real testament to this movie that Yang Chao is able to get into these ideas without pointing at them directly. It’s hard to avoid descending into bland platitudes or esoteric superstition when talking about the tao, and like many things Made in China today, Taoism has long since been re-fashioned into a cheap commodity—a take-out religion for the New Age.3

So while Crosscurrent isn’t shy about it’s art house aspirations, there’s nothing wrong with that. More importantly perhaps, by re-introducing a much needed sense of polysemy and spooky spiritualism, the film resists the cheapening of Chinese religion, with some clear antecedents in the literary tradition. The understated environmental message, which will likely end up getting ignored by most reviewers of the film, is equally important, and something I’m going to need to think about further—especially when compared to the much more direct messages of the Mermaid and Under the Dome.

In any case, it’s one hell of a good film.

EDIT 10/11/2016:

- Both of which are included in Y.W. Ma and Joseph S.M. Lau’s definitive collection of English translations, Traditional Chinese Stories: Themes and Variations (Cheng & Tsui, 1986). [↩]

- Mark Lee Ping-Bing, who also served as director of photography for Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and cinematographer for Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s The Assassin, won the Silver Bear in Berlin for his work on the film. [↩]

- I can’t pretend to have a deep familiarity with foundational Taoist texts like The Book of Changes or the Zhuangzi, but I’ve been as guilty of this as anyone else who read the Dharma Bums as a teenager. [↩]