UPDATE 3/8/2017: The website of the Jia Pingwa Project (which has since been renamed ‘Ugly Stone,’ in honor of Jia’s short story of the same name) is now live, with sample translations of The Poleflower, Shaanxi Opera, and Old Kiln Village. A final sample translation of Master of Songs is currently under consideration for the Asymptote Close Approximations fiction contest. Additionally, just last month, a short piece by YT on Jia and his work was featured on the blog of the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative, and Professor Jiwei Xiao announced that the Modern and Contemporary Chinese Forum would be sponsoring a roundtable on the same for the 2018 Modern Literature Association conference in New York City.

So, in March I met Jia Pingwa 贾平凹.1 Even if you’re familiar with Chinese literature in translation, you might not have heard of Jia, despite his towering presence in contemporary Chinese literature. That’s because very few of his books have been translated into English–the first was his 1988 novel Turbulence, translated by Howard Goldblatt and published by Louisiana State University Press after winning the Mobil Pegasus Prize for Literature in 1991.2 Goldblatt, of course, is also the translator of Mo Yan, whose 2012 Nobel prize win seemed (if ever so briefly) to indicate that the tide was finally starting to turn for the reception of Chinese literature in translation.

Jia is fourth from the left, beanstalk in plaid is your humble author

Much more recently, Goldblatt returned to Jia’s work with his translation Ruined City, the second ever English language translation of a novel length work by Jia, published by Oklahoma University Press in January, 2016, as part of their Chinese Literature Today series. Perhaps on account of having been published by an academic press, so far this book has been largely ignored by mainstream critics with a single, solitary review in the New York Times. Lumped together with two other books under the telling title “Banned in Beijing,” Jess Row’s review has a less than promising start:

The Chinese title of this sprawling novel, “Feidu,” means “abandoned capital.” It refers not to Beijing but to Jia Pingwa’s hometown, Xi’an, called Chang’an when it was the political and spiritual center of the Tang dynasty. In its time possibly the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the world, Xi’an (Xijing in the novel) has, in Jia’s description, become a dilapidated backwater by the 1980s.

In fact, the English translation of ‘Abandoned Capital,’ used to refer to work prior to Goldblatt’s translation, seems to have been inspired not by the Chinese original, but instead the award-winning 1997 French translation by Genevieve Imbot-Bichet as La Capitale déchue, meaning something like the ‘Fallen Capital’ or the ‘Deposed Capital.’ In Chinese, the title is much more ambiguous, with the first character, 废, meaning both ‘abandoned’ (in the sense of ‘ruins’ 废墟 or ‘scrap/waste’ 废品), but equally a thing which has been ruined or abolished, as when one nullifies a treaty 把条约废了,ruins ones body / happiness 把身体/幸福废了 or to ‘end someone,’ as in the title of the popular web novel 特工皇妃:皇上我要废了你 (‘Special Agent Imperial Concubine: Emperor, I Will End You’). The second character, 都, is also tricky, because it can mean both ‘capital’ 首都, and also ‘city,’ as in 大都市 (‘major metropolis’). In a short translators note at the end of the novel, Goldblatt explains that

…when I asked Jia how he wanted it to be rendered, he said he preferred “city” over “capital,” since the latter no longer applied, and asked for a term of destruction, not abandonment, as some critics and scholars have used, in the title.

My second ‘beef’ (albeit a minor one) with the opening lines of Row’s review of Ruined City, is the contention that Jia portrays Xi’an/Xijing as a “dilapidated backwater.” My impression of the novel is that there is little description of the city itself, with the vast majority of the text devoted to Zhuang Zhidie and his shifting cast of friends, lovers, collaborators, and hangers-on. That said, the remaining two and a half paragraphs of Row’s is dedicated to these players and the classical texts that Jia is playing off of, displaying a great deal more nuance than in first two lines when he describes the novel as showing a

…pervading nostalgia for the Chinese past, embodied in the novel’s episodic, wandering, seemingly plot-indifferent structure — a series of what seem to be very similar incidents and encounters, meals, conversations, sexual escapades, minor scandals and subdued confrontations, which only by very slow degrees add up to any sense of narrative progress. Like some of the classics of Chinese literature — “The Water Margin,” “Journey to the West,” “The Dream of the Red Chamber,” “The Scholars” — “Ruined City” has to be appreciated for its small pleasures as much as its larger themes…

Cover of Goldblatt’s translation of Ruined City, featuring the fantastic Short-Lived Four Flower Bloom planted by Zhuang Zhidie and Meng Yunfang in soil from the grave of Yang Guifei and correctly divined by Abbot Zhixiang.3

Likewise, M.A. Orthofer, of the Complete Review, has also written an excellent review of the novel, expounding upon the themes of “everyday wrack and ruin” that Jia uses to build up to his “quietly devastating” conclusion. I think this gets to the heart of why Jia has been such a hard sell in English–for readers expecting blunt and obvious criticism of contemporary Chinese politics, there is little (on the surface level at least) to suggest to that Jia or his characters see anything wrong with the status quo. While similar criticisms have been leveled at Mo Yan, unlike his contemporary from Shandong, Jia hasn’t had good fortune to find an advocate like Goldblatt to translate his novels into English (with the exception of the already mentioned two). Although I’m obviously biased, having been invited to translate his most recent novel, The Poleflower, 4 I would argue that Jia is one of the sharpest social critics writing in China today–just not in the way that you might expect. As Orthofer writes in his review of Ruined City:

Early on, Zhuang Zhidie wonders: “Am I adapting to society or becoming corrupt ?” and it is one of the basic questions of the novel. Jia’s depiction of this city and society is of one corrupted not so much politically (though how much connections matter is a prominent feature in the story) but morally and culturally. Even pesticide — the simplest poison — is a fraud in this world. (Among Jia’s other amusing examples is that of a young writer who tries to go into the steaming buns business but can’t get the recipe right; a cook reveals the secrets to a proper bun: “adding yeast, powdered laundry detergent, and chemical fertilizer, after which the buns were smoked in sulfur” …..)

While Jia is, to be fair, as just as much of an ‘insider’ as Mo Yan, I get frustrated (and others do as well) when dissidents writers are held up as the sole worthy inheritors of Chinese literature and culture. While I applaud writers such as Liao Yiwu and Ma Jian who stand up for what they think is right, I think we do authors like Jia and Mo Yan a disservice when we criticize them for failing to speak out in the same way. Not living in China, I can’t pretend to be anything more than an observer of Chinese culture (although, having studied the language for over 10 years and two degrees, not to mention having married into a large extended family from 东北, it would not be a stretch to say I’ve got a vested interest the place). The more that I observe of China, and the world in general, the more I come to appreciate the use of ambiguous and complex messages rather than bold ultimatums. I’d like to think the world is a big enough place to allow for the existence of both.

In that spirit, I’ve agreed to help Jia make more of his work available in English. My own part of this project, aside from a 20,000 character sample translation and reader report of The Poleflower, has been to coordinate and edit sample translations and reader reports of three other novels: Old Kiln Village 《古炉》, to be translated by Nicky Harman, Shaan’xi Opera 《秦腔》, to be translated by Dylan Levi King, and The Funeral Singer Master of Songs 《老生》, to be translated by Brendan O’Kane yours truly. I have to say, I’m really excited to be working with such a great group of translators and writers–hopefully we’ll be able to do Jia justice in English! Funding has generously been provided by the Jia Pingwa Art and Culture Center in Xi’an 贾平凹文化艺术研究院, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting scholarship on Jia’s work. If everything goes according to schedule, copies of our samples should be online and in print by September of this year.

Finally for non-Chinese speaking fans of Jia’s work who have already read Turbulence and Ruined City, there is even more good news on the horizon: Nicky Harman’s translation of Jia’s 2007 novel Happy is scheduled to be published by AmazonCrossing in the Spring of 2017, and Carlos Roja’s translation Jia’s 2013 novel The Lantern Bearer should be appearing shortly before or after this book is published by CNBooks of New York. Given the number of translations in the works, perhaps when it comes time to write a follow up post to this one some months or years from now, Jia will have already begun to receive some of the attention he deserves in English. And if you haven’t read any of Jia’s work, here’s a great place to start: his 1981 essay, The Ugly Stone, translated by the godparents of Chinese literature in translation, Gladys and Xianyi Yang.

- Yes, 凹 is usually pronounced āo, not wā. An explanation of his pen name is available here. [↩]

- In 2003 Goldblatt’s translation was republished by Grove Press. Most editions I’ve come across are from this later reprinting. [↩]

- See Chapter 1 of the novel. [↩]

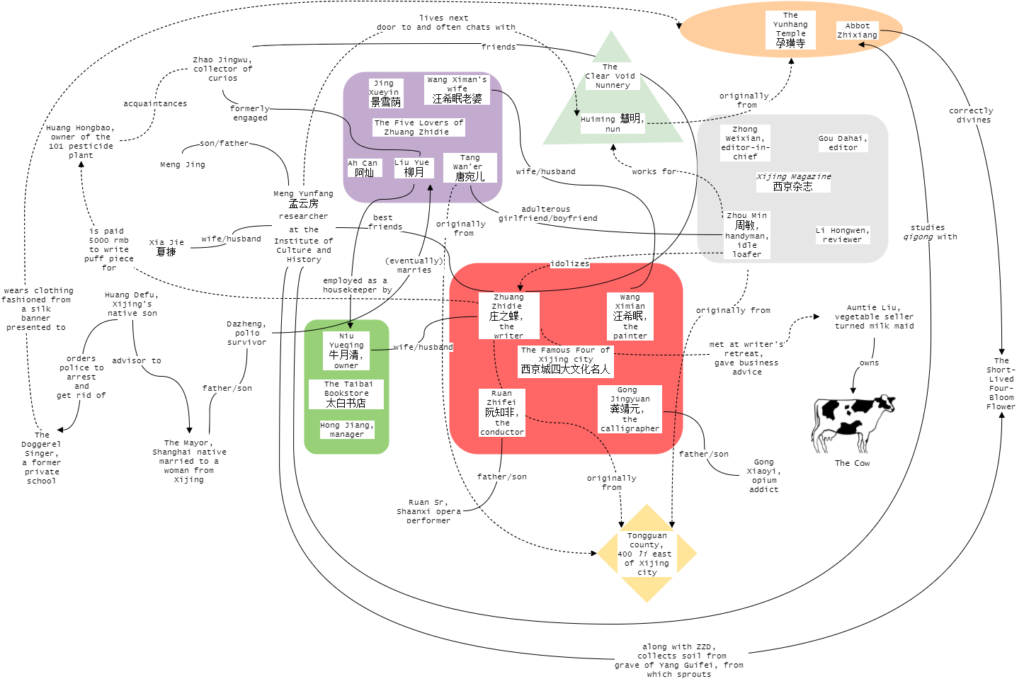

- In Chinese, the title of this book is 《极花》, and refers to a (made-up) flowering grass which parasitizes a species of caterpillar in rural Shaan’xi, similar to Ophiocordyceps sinensis of Tibet and Gansu. It was published in March, 2016 by People’s Literature Press 人民文学出版社. For an in-progress character map of the novel, click here. [↩]