This is the third chapter in my MA thesis, The Shanghai Manhua Society: A History of Early Chinese Cartoonists, 1918-1938, completed in December 2015 at the Department of Asian Studies at UBC. Since passing my defense, I’ve decided to put the whole thing up online so that my research will be available to the rest of the world. I’ve also decided to use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can share it with anyone you like, as long as you don’t charge money for it. Over the next couple of days I’ll be putting up the whole thing, chapter by chapter. You can also download a PDF version here.

Ji Xiaobo, Ding Song, Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhengyu, and Lu Shaofei all met in the late 1910s, and found an affinity in their shared interest in cartooning, and also perhaps a sense of social exclusion, since all four men were born into a merchant or tradesmen families. Their relative lack of education stands in contrast with many Republican-era intellectuals and artists who came from wealthy families and were educated abroad. Although Ye Qianyu was given the benefit of a high school education, and was also somewhat younger, like the Zhang brothers and Ye Qianyu, he seems to have mostly forged his own path to becoming recognized as a professional artist.

The remaining members of the Manhua Society are Wang Dunqing, Huang Wennong, Hu Xuguang, Zhang Meisun 張眉蓀 (1884-1975) and Cai Shudan 蔡輸丹 (n.d.). Of them, Zhang Meisun seems to have been an early acquaintance of Ding Song, having studied art together at Tushanwan orphanage while both men were in their teens, and Hu Xuguang a student of Ding Song, having studied at the Shanghai Art Academy. The rest, like Ye Qianyu, seem to have been wild cards, attracted to Manhua Society by chance encounters and shared interests. Some, like Zhang and Cai, don’t seem to have left any cartoons behind, with Zhang becoming a well-known painter of watercolors, and Cai working as an assistant to Ji Xiaobo.[1]

Ye Qianyu has mentioned that he first became interested in cartooning after seeing cartoons by Huang Wennong, who himself may have been influenced by Shen Bochen without ever meeting him. Wang Dunqing, meanwhile, quickly rose through the ranks of the Manhua Society, taking over the chair from Ding Song in November, 1927. He made fast friends with Ye Qianyu, but seems to have remained distant from many of the other members of the society.

Wang Dunqing: The Boy Scout

Born in 1899 in Wangjiangjing 王江涇鎮, a prosperous village near Jiaxing 嘉興 city, located to the south of Shanghai, Wang Dunqing is unique among the founding members of the Manhua Society for his high level of education, having earned a BA from the prestigious English-language St. John’s University 聖約翰大學. During his time at St. John’s Wang was an active member of the Boy Scouts 童子軍, while also serving as the club president of the Illustration Research Society 圖畫研究會. The former appears to have been under the influence of Donald Roberts, a professor of English and History who organized the St. John’s Boy Scouts troop in 1917. [2] Roberts, an avid collector of early Republican-era illustrated broadsheets, may have encouraged the young Wang to pursue his interests in cartooning. By the time he graduated with his BA in 1923, Wang was set on a career in the arts. Following a short stanza from Longfellow’s 1878 poem Kéramos,[3] his yearbook biography modestly proclaims (in English):

With a glance at the picture, you can immediately tell who he is. It is not strength, but his fine character and art that win the love and admiration of all his fellow students. As a friend, he is always sincere and ready to help without hesitation. As an athlete, he is noted for his fine college spirit. His beautiful verses in Chinese are depictable [sic] of humanity and true to nature. His clear perception with a firm, bold hand marks him a true artist of distinction. With such an intelligence, capacity and character, we are sure that a bright future awaits him.[4]

Following graduation, Wang prepared to go abroad for further study. His father’s sudden death interrupted these plans, however, forcing him to stay in Shanghai. In June, 1923 he was hired to teach English at the Yaqiao Academy 亞喬書院, along with fellow Johannean Yang Deshou 楊德壽 (n.d.),[5] a progressive institution which offered “half-off tuition to all female students for the sake of popularizing women’s education” 因普及女子敎育起見、凡女生來學者概收半費.[6] By August a second notice announced that the school had enrolled more than 60 students and that placement exams would be conducted in September.[7]

Wang Dunqing seems to have been introduced to the Manhua Society by Lu Shaofei through their mutual friend, Wang Yingbin 汪英賓 (1897-1971), who provided the inspiration for Lu’s first cartoon in the Shenbao (see figure 3.1). Wang Yingbin had graduated with a diploma of college completion 大學畢業學位證書from the department of China Studies 國學 at St. John’s University in 1920.[8] While at St. John’s, in addition to his studies Yingbin worked as the illustration editor for the school yearbook, The Johannean 約翰年刊. That same year, Wang Dunqing also graduated with his diploma from the department of China Studies at St. John’s, and by virtue of their last names, both he and Yingbin were featured on the same page of the Chinese language supplement of that year’s yearbook.[9] After graduating in 1920, Yingbin was hired as an art editor at Shenbao, becoming an important figure in the publishing world.[10] Wang, meanwhile stayed on at St. John’s for another three years, earning his Bachelor of Arts in 1923. [11]

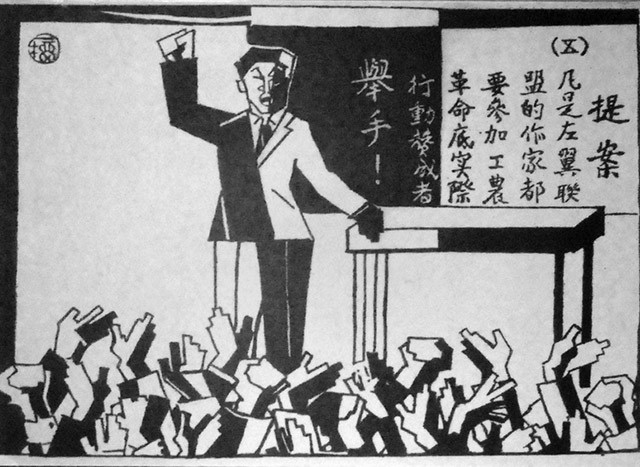

While little of his work from the this time period has survived, by the late 1920s, Wang Dunqing had begun to publish cartoons under various pseudonyms, including Wang Yiliu 王一榴, Wang Luzhen 王履箴, Huang Cilang 黃次郎, even using Wang Jiangjing 王江涇, the name of his hometown, as a pen name at one point. The purpose of these pseudonyms seems to have been to disguise his close association with the political left: one of the most well-known cartoons credited to Wang Yiliu depicts the first meeting of the League of Left-Wing Writers 中國左翼作家聯盟 (Left League 左聯) on March 2, 1930.

Figure 3.1 Wang Yiliu [aka Wang Dunqing] “Founding of the League of Left-Wing Writers” 左联作家联盟成立 Shoots萌芽, Issue 4, April 1930, 7.

Organized at the behest of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and leading leftist social critic Lu Xun, the Left League was founded to promote socialist realism in Chinese art and literature. Other prominent members included the writers Guo Moruo 郭沫若 (1892-1978), Mao Dun 矛盾 (1896-1981), and Ding Ling 丁玲 (1904-1986) and the playwrights Tian Han 田漢 (1898-1968) and Xia Yan 夏衍 (1900-1995). Due to the influence of Lu Xun, the Left League included a number of woodcut artists. Although Wang Dunqing’s illustration of the founding of the Left League does not appear to have been made using a woodcut, the use of sharp, angular lines and solid blacks suggests a stylistic debt of inspiration.

As Paul Bevan points out (relying on the work of Wong Wang-chi), also present at the founding meeting of the Left League on March 2, 1930, was the cartoonist Huang Shiying 黄士英 (?-?). Huang would go on to launch a string of controversial manhua publications in the 1930s, beginning with Manhua Life 漫畫生活 in June, 1934.[12] His first connection to manhua, however, can be traced back to this first meeting of the Left League, where he proposed the formation of the Chinese Manhua Research Society 中國漫畫研究會 and the May Day Pictorial 五一畫報, likely with the encouragement of Wang Dunqing.[13] Although the proposed pictorial never materialized, the Manhua Research Society did eventually hold their first meeting, one year later, on June 9, 1931.[14]

The Left League, meanwhile, was thrust into the limelight when five prominent members were arrested at a secret meeting of the CCP in the International Settlement and executed by firing squad at Longhua Prison by the KMT government on February 7, 1931. As a member of the Left League, Wang Dunqing contributed cartoons to their publications Shoots 萌芽 and Pioneer 拓荒者. Wang later claimed to have been forced to go into hiding for several years following the crackdown, but given his use of pseudonyms, he may simply have meant that he stopped publishing cartoons under his own name during this time. [15]

Huang Wennong: The Missionary’s Son

Unlike Wang Dunqing, Huang Wennong was born in a family of relatively humble means. Somewhat uniquely, however, his parents were converts to Christianity, working as missionaries in Songjiang county 松江, just to the south of Shanghai. In 1919, when he was just 16, Huang was apprenticed to a copyist for the lithographic press of Chunghwa Book Company 中華書局. Founded by former employees of the Commercial Press 商務印書館, the Chunghwa Book Company got its start printing textbooks for newly formed Republic of China following the fall of Qing dynasty in 1911 and went on to become one of Republican Shanghai’s “big three” publishing houses.[16] Despite his lack of formal education, Huang proved to a quick study and within three years was promoted to working as an editor on the bimonthly children’s magazine Kids 小朋友, launched on April 6, 1922.

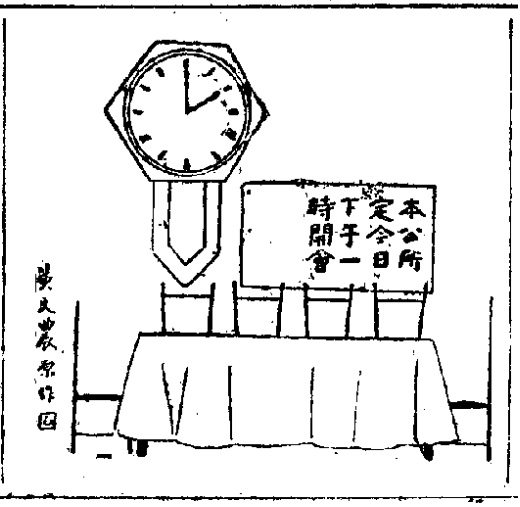

Although most secondary sources record that Huang Wennong did not begin drawing cartoons until 1925, he actually seems to have begun drawing and publishing cartoons much earlier. It is likely that many of the illustrations in Kids are his work, although since they are, as a rule, uncredited it is hard to say to for sure. The earliest published cartoon I have been able to find that is credited Huang Wennong was published in the Shenbao on March 20, 1921. It depicts a vacant table, set with six high backed chairs. On the wall behind the table a large clock set into a hexagonal base displays the time: two o’ clock sharp. Just to the left of the clock a sign reads, “This public office will hold a meeting this afternoon at 1:00pm.” Even in this early cartoon one can see Huang’s satirical style starting to emerge. Unlike Ding Song, who found his humor in physical deformities, or Zhang Guangyu, who tended to rely on subtle allegories, Huang Wennong was surprisingly direct in his criticism of the government.

Figure 3.2 Huang Wennong “Our Office Will Have a Meeting at One o’clock Today” 本公所定今日下午一時開會 Shenbao Sunday, March 20, 1921, 18.

Notices from the same year suggest that Huang was a regular contributor to the Shenbao, meaning that he would have meet Wang Yingbin, Hu Xuguang and likely Wang Dunqing around this time. It is also possible that his parents knew Ding Song through mutual acquaintances at the Tushanwan orphanage. In 1914, Ding Song, Liu Haisu, and Zhang Yuguang co-authored a best-selling how-to-draw book for the Chunghwa Book Company. Although Huang didn’t become an apprentice at the press until five years later, in 1919, he may have read a remaindered copy of the book as part of his informal training.

In June, 1924, Huang formed the Chinese Painting Film Studio 中國畫片公司with Li Yunchen 李允臣 and Shen Yanzhe 沈延哲 (n.d.).[17] Within four months he had completed China’s first “moving cartoon” 活動滑稽畫 film, The Dog Entertains 狗請客, a 30-minute long mix of live action and hand drawn animation.[18] Plans were made to complete further animated films, including an ambitious adaption of Journey to the West 西遊記, but the Zhonghua Film Studio went bankrupt within the year and Huang was left trying to subsidize his film by creating cartoons for various periodicals.[19]

In early 1925 he took over the staff cartoonist position at The Crystal from Zhang Guangyu, which earliest definitive evidence that I have been unable to uncover of Huang Wennong collaborating with other Manhua Society members. Shortly thereafter Huang took on a similar position for the Commercial Press’ long-running flagship magazine, The Eastern Miscellany 東方雜志. While his cartooning career was clearly taking off, his animated films seem to have floundered due to a lack of funds. For Huang, then, cartooning may have represented the next best thing to creating animated films. One side effect of his earlier career, though, seems to have been a tendency to draw quickly, something which Ye Qianyu remembers being impressed by when they first met.

Hu Xuguang: The Lumberjack

In common with Huang Wennong, Hu Xuguang (pen name Ming Dong 明東) was also from Songjiang county. Born in 1901 in the town of Sijing 泗涇鎮, his father, who worked in the lumber trade, died when he was only 14. After graduating from elementary school, he was apprenticed to a lumber trader in Xinzhuang 莘莊鎮, studying drawing and painting in his free time. His hobby attracted the attention of Fan Yichun 範亦純 (n.d.), the son of the lumber trader to whom he was apprenticed. Yichun convinced his father to fund Hu’s education in Shanghai, where he managed to test into the Shanghai Art Academy. Like Zhang Guangyu, his talent and hard work made a strong impression on Zhang Yuguang and Ding Song, who would become lifelong friends. After graduating in 1920, Hu worked as a commercial artist for a variety of businesses in Shanghai. He seems to have done well for himself, and by March, 1923, he had married Lu Jiezhen 陸潔貞 (n.d.) in a ceremony in the ballroom of the Zhenhua Hotel 振華旅館, with Zhang Yuguang (Ding Song’s close friend and Zhang Guangyu’s mentor) acting as witness and the journalist Hang Shijun 杭石君 acting as his best man. [20]

Figure 3.3 Hu Xuguang “Candle in the Wind” 風中之燭, Shenbao, Thursday, January 6, 1921, 16.

Hu Xuguang was extremely active in the Shenbao during the early 1920s but seems to have disappeared following the dissolution of the Manhua Society in late 1927. As far as I can tell, he does not seem to have participated in the numerous manhua publications of the 1930s, or the anti-Japanese propaganda troupes of war period. This is curious, given the overt political messages of his cartoons from the early 1920s. For example, one representative cartoon from early 1921, titled “Candle in the Wind” shows a disembodied hand holding a candle labeled “Militarism” 軍國主義. The flame of the candle is nearly horizontal, sputtering in the wind which is labeled “Mainstream Spirit of the Times” 時代潮流. Cupped around the flame is a second disembodied hand labeled, “Warlords” 軍閥. Given that the warlords were not overthrown until the Northern Expedition, more than half a decade later, Hu Xuguang was clearly making full use of the extraterritorial protections afforded by Shanghai to express his discontent with the status quo. He was careful, however, not to call out a specific warlord or faction.

Continued in Chapter 4…

[1] Zhang Meisun’s watercolors have appeared at auctions in mainland China. See for example “Xidamochang jie shuicai zhiben paimaipin_jiage_miaoshu_jianshang_(shuicai) – Bobao Yishu Paimai Wang” 【西打磨廠街 水彩 紙本】 拍賣品_價格_圖片_描述_鑒賞_(水彩) -博寶藝術品拍賣網 [West Damochang Street Watercolor Paper Version Auction Item_Price_Picture_Description_Appreciation_(Watercolor) – Artxun Art Auction Net], 博寶拍賣網, n.d., http://auction.artxun.com/paimai-119504-597519148.shtml (accessed September 11, 2015). According to the short biography included on Artxun, Zhang’s work has also collected into a three volume set titled Meisun Shuicaihua Linben 眉蓀水彩畫臨本 [An Overview of the Watercolors of Zhang Meisun] (Hebei Renmin Chuban She 河北人民出版社, 1963).

[2] Donald Roberts graduated from Princeton in 1909 and was hired at St. John’s University in 1915 where he continued to teach until 1950. In 1917, in addition to organizing the Boy Scout troop at St. John’s, he also joined the Volunteer Corps of the Ministry of Works 工部局義勇軍. He attended Columbia during a sabbatical in 1919 and was eventually ordained an Episcopalian minister. See “The Alumni,” Princeton Alumni Weekly XX, no. 9 (1919): 210, “Lao zhaopian: shanghai sheng yuehan daxue xiaoyuan de shenyun” 老照片:上海圣约翰大学校园的神韵 [Old Photos: The Charm of Shanghai St. John’s University Campus], July 8, 2011, http://bbs.wenxuecity.com/memory/394958.html (accessed March 12, 2015). and “Block Prints of the Chinese Revolution – Princeton University Digital Library,” n.d., http://pudl.princeton.edu/collections/pudl0030 (accessed March 12, 2015).

[3] “Art is the child of nature; yes / Her darling child in whom we trace / The features of the mother’s face / Her aspect and her attitude.” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Longfellow’s Poetical Works: Author’s Complete Copyright Edition (London: George Routledge & Sons, 1883), 609. Perhaps not coincidentally, this exact quote is also included under the heading of “Art” in the popular reference work The Cyclopæaedia of Practical Quotations (Funk & Wagnalls, 1886), 15.

[4] “Wang Tung-Chung (Wang Tun-Chung) B.A. Chekiang,” Yuehan Niankan 約翰年刊 (1920): 70.

[5] BA in Economics in 1923. See “Yuehan daxue zuori zhi shenghui” 約翰大學昨日之盛會 [St. John’s University Ceremony Yesterday], Shenbao 申報, July 1, 1923.

[6] “Xuewu congzai” 學務叢載 [Selection of School Affairs], Shenbao 申報, July 17, 1923.

[7] “Xuewu congzai” 學務叢載 [Selection of School Affairs], Shenbao 申報, August 26, 1923.

[8] “Yuehan daxue juxing biye liji” 約翰大學舉行畢業禮紀 [St. John’s University Holds Graduation Ceremony], Shenbao 申報, June 28, 1920.

[9] The historian Li Jie serendipitously includes this page of The Johnnean in an essay on Wang Yingbin. See Li Jie 李洁, “民国报人汪英宾探微:兼及相关文献资料勘误” [Republican Journalist Wang Yingbin: An Investigation and Some Corrections to Errors in the Relevant Literature], Xinwen Chunqiu 新闻春秋 no. 03 (2014): 56–61 and “Zhongwen biyesheng xiaoxiang bing timing lu” 中文畢業生小像並題名錄 [Chinese Supplement: Pictures of Graduating Students and Biographical Information], Yuehan Niankan 約翰年刊 (1920): 24.

[10] Wang Yingbin would go on study Journalism at the University of Missouri in 1922, later transferring to Columbia University where he earned a Masters of Science in Journalism. His thesis on the development of Chinese-language newspapers, Rise of the Native Press in China (New York : Columbia University, 1924), was the first in depth English-language study on this topic.

[11] While his yearbook biography from 1923 doesn’t include his major, the Shenbao announcement indicates that he earned his BA文科學士from the school of liberal arts, meaning that he was undeclared. See “Yuehan daxue zuori zhi shenghui.”

[12] Bevan, A Modern Miscellany, 29 and Wong Wang-chi, Politics and Literature in Shanghai: The Chinese League of Left-Wing Writers, 1930-1936 (Manchester University Press, 1991), 62–63, 92.

[13] Apparently unaware of Wang Dunqing’s use of the pseudonym Wang Yiliu, Bevan mistakingly claims that no members of the Manhua Society were present at the first meeting of the Left League. See A Modern Miscellany, 29.

[14] “Zhongguo Manhua Yanjiu Hui Chengli” 中國漫畫研究會成立 [Chinese Manhua Research Society Founded], Shenbao 申報, June 9, 1931, 10; Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua Shenghuo” 漫畫生活 [Manhua Life], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷 (Shanxi Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 陝西人民美術出版社, November 2000), 600–601.

[15] Wang suggests as much to Jack Chen in his 1938 interview. Chen writes that Wang went in hiding directly after the 1927 split between the left-wing KMT in Wuhan and right-wing KMT under Chiang Kai-shek in Nanjing, I think he may be confusing this with falling out between Wang Dunqing and Zhang Zhengyu that led to him cutting ties with the Manhua Society from 1928 to 1931.

[16] For more on the major publishing houses of Republican-era Shanghai, see Chapter 5 of Christopher A. Reed, Gutenberg in Shanghai: Chinese Print Capitalism, 1876-1937 (UBC Press, 2011).

[17] “Zhongguo huapian gongsi chengli” 中國畫片公司成立 [Chinese Painting Film Studio Established], Shenbao 申報, June 24, 1924, 22nd ed.

[18] As far as I am aware, the film has not survived, although stills may exist in magazines or newspapers. I have not been able to find any however.

[19] Yin Fujun 殷福軍, “黃文農早期動畫創作研究” [Research into Huang Wennong’s Early Animations], Dianying Wenxue 電影文學 no. 09 (2010): 29–30.

[20] “Hu Xuguang Zuori Jiehun” 胡旭光昨日結婚 [Hu Xuguang Got Married Yesterday], Shenbao, March 18, 1923, 1st ed., 18.