This is the second chapter in my MA thesis, The Shanghai Manhua Society: A History of Early Chinese Cartoonists, 1918-1938, completed in December 2015 at the Department of Asian Studies at UBC. Since passing my defense, I’ve decided to put the whole thing up online so that my research will be available to the rest of the world. I’ve also decided to use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can share it with anyone you like, as long as you don’t charge money for it. Over the next couple of days I’ll be putting up the whole thing, chapter by chapter. You can also download a PDF version here.

Given Ji Xiaobo’s job as a censor for the Nationalist government in the 1930s, it is perhaps unsurprising that when Ye Qianyu wrote his autobiography in the late 1980s, he decided not to mention that Ji Xiaobo was an old acquaintance of two key founding members of the Manhua Society, Zhang Guangyu and Ding Song. Since Ji Xiaobo claims to have met both in 1917, while working Sun Xueni’s Shengsheng Fine Arts Press, it stands to reason that Ji Xiaobo would have introduced the two cartoonists to Ye Qianyu when the talented young artist was promoted to the advertising department of Three Friends in 1925.

Instead, Ye recalls that he met Zhang Guangyu after submitting a cartoon to his tabloid, the China Camera News 三日畫報in the summer of 1925, shortly after arriving in Shanghai.[1] There may be an element of pride at work here as well, because according to Ye, Zhang was so impressed with his work that he asked to meet him in person. Or it may be that Ji never introduced them, and Ye resented him for not having done so. Regardless, it seems clear that Ye Qianyu and Zhang Guangyu hit it off almost immediately, with the younger Ye referring to Zhang as “the first of the older generation of manhua artists I met” 最早认识的老一辈漫画家. This, again, is curious, because Zhang, born in 1900, was only one year older than Ji Xiaobo.

In comparison, Ye hardly mentions Ding Song. Given their respective ages, Ye Qianyu and Ji Xiaobo were likely much closer friends with Zhang Guangyu than they were with much older Ding Song. Nevertheless, Ding Song seems to have provided the group with a certain amount of guidance. Meeting notes for the society indicate that Ding Song was the chairperson of the group for the majority of 1927, stepping down in favor of Wang Dunqing in November, and he was a teacher and mentor to both Zhang Guangyu and Lu Shaofei. Most importantly perhaps, as the oldest member of the Manhua Society by nearly a decade, Ding Song is in many ways typical of the cartoonists who emerged in the first decade of the Republic prior to the formation of the Manhua Society.

Ding Song: The Grandfather

Born in 1891 in Fengjingzhen 楓涇鎮, a small town in Jiashan county嘉善to the southwest of Shanghai, Ding Song’s parents both died when he was only 12. He spent his teen years at the Tushanwan土山灣orphanage in Xujiahui district, which had been founded by Jesuit missionaries in 1864.[2] While at Tushanwan, Song studied Western religious and secular art with Zhou Xiang周湘 (1871-1933) and Zhang Yuguang張聿光 (1886-1968), in addition to learning how to operate a printing press. He quickly made a name for himself as an artist, and in 1913, Song was invited to serve as academic dean for the newly founded Shanghai Art Academy 上海美術院 , later being promoted to provost.[3] It was around this time he became close friends with the prolific cartoonist Shen Bochen沈泊塵 (born Shen Xueming 沈學明, 1889-1920), who had been hired as a staff cartoonist for the three-day tabloid The Crystal 晶報in 1912.[4] Under Shen’s encouragement, Ding Song to soon began drawing and publishing his own cartoons.

In late 1913, Ding Song helped launch the monthly magazine Unfettered Magazine自由雜誌, edited by Tong Ailou童愛樓 (n.d.). [5] In December, Ding Song and others continued the magazine under a new name, The Pastime 游戲雜志, edited by Wang Dungen 王鈍根 and Chen Diexian 陳蝶仙. Starting in 1914, Ding Song also became a regular contributor to The Saturday 禮拜六, drawing numerous full color covers for the magazine. As an artist, Ding Song excelled at drawing the human form, in particular intimate portraits of beautiful women. Much of the humor in his work, however, comes from the juxtaposition of grotesque caricature with ironic titles. For example a 1921 cartoon titled, “Falling in Love” 戀愛 depicts an obese, bald, and drooling woman with two pinhole eyes. A pigeon-toed man, presumably her husband or lover, stands behind her, holding her shoulders and gazing down at her affectionately.[6] Beside them, an overweight dog ambles along on stubby legs, his vacant expression inviting comparison with the hideous woman. Years later, similar works by Shen Bochen would come under fire from the preeminent Republican-era author and critic, Lu Xun魯迅 (1881-1936) who Geremie Barmé surmises found that his satirical drawings were an “essentially conservative and xenophobic populist art form” under its “flash Western exterior.”[7] Writing in his particularly bombastic style in late 1924, Lu Xun concluded,

While [the artist Shen Bochen] draws in style which is copied from the West, I am amazed that he is so antediluvian, and that he has such a vile personality. He is no better than a child who scribbles “so-and-so is my son” [sic] on nice white walls. Pity all things that come from abroad: once they cross our borders it is as if they have fallen into a vat of black dye, for they lose their original cast. Art is but one example of this. Even before we learn to draw nudes in proportion people busily set to work producing pornographic paintings; artists who have yet to grasp the principles of chiaroscuro when painting still lives churn out advertisements cheerfully. This is what happens when change is only superficial; at heart things are as of old. It is hardly surprising, then, that once introduced satirical paintings were immediately employed by people wanting to engage in character assassination.

[沈泊塵] 的畫法,倒也模仿西洋;可是我很疑惑,何以思想如此頑固,人格如此卑劣,竟同沒有教育的孩子只會在好好的白粉牆上寫幾個“某某是我兒子”一樣。可憐外國 事物,一到中國,便如落在黑色染缸裏似的,無不失了顏色。美術也是其一:學了體格還未勻稱的裸體畫,便畫猥褻畫;學了明暗還未分明的靜物畫,只能畫招牌。 皮毛改新,心思仍舊,結果便是如此。至於諷刺畫之變為人身攻擊的器具,更是無足深怪了。[8]

Figure 2.1 Ding Song “Falling in Love” 戀愛Shenzhou Pictorial神州畫報, January, 1918, 84.

Notwithstanding the future criticisms of Lu Xun, on September 1, 1918, Shen Bochen launched his own monthly bilingual humor periodical Shanghai Puck上海潑克, passing his duties at The Crystal on to Ding Song.[9] Ding would later hand this job off to Zhang Guangyu, who would in turn pass the torch to Huang Wennong in early 1925. With the help of Ding Song and other cartoonists, Shen and his brother, Shen Xueren 沈學仁, managed to publish three more issues of Shanghai Puck, also known as Shen’s Comic Pictorial 泊塵滑稽畫報 , before Shen succumbed to tuberculosis. Following Shen Bochen’s death on March 7, 1921, Shen Xueren held an exhibition of his work in his honor. Over the next several years, cartoon exhibitions would become an important method of promoting manhua artists and their publications.

Around the same time as Shen Bochen began publishing Shanghai Puck, the first issue of World Pictorial appeared on August, 1918. Published by Sun Xueni’s Shengsheng Fine Arts Company, the first ten issues of World Pictorial were edited by Xueni and his assistant, Xu Yiou許一鷗 (n.d.). Beginning with the eleventh issue, Xueni hired Ding Song to edit the magazine, who in turn brought Zhang Guangyu on as his assistant, which is where both men met Ji Xiaobo, who was working on Xueni’s newspaper, Shanghai Resident News. Both Ding Song and Zhang contributed a large number of humorous drawings and illustrations to the Xueni’s publications, and likely did much to inspire the younger Ji Xiaobo in his decision to become a cartoonist. Although illustrated magazines had been around since the 1880s, satirical cartoons had only become commonplace in China over the previous decade, with the social unrest of the 1910s fueling their popularity.

Ding Song continued to work in cartoons after Shen Bochen’s death from tuberculosis in 1920. As an instructor at the Shanghai Art Academy, Ding Song made a point of introducing his students to a wide variety of Western-influenced artists through the Heavenly Horse Society 天馬會. Co-founded by Ding Song with and five other Shanghai Art Academy instructors in September, 1919, this group was incredibly influential in the world of modern art in Shanghai, with over 200 artists participating in its first exhibition. In 1921, Zhang Guangyu, Ji Xiaobo, Lu Shaofei joined a second artist’s association, the Aurora Art Club晨光美術會, also founded by Shanghai Art Academy instructors. These organizations seem to have provided the young artists not only with opportunities to expand their social networks, but also a blueprint for the nascent Manhua Society.[10]

Zhang Guangyu: The Godfather

If Ding Song was the “Grandfather” who provided the younger members of the Manhua Society with a ready role model, then Zhang Guangyu could be called the “Godfather,” for his role in bringing the group together and securing funds to bankroll their publications. Zhang could be seen as a more successful and talented version of Ji Xiaobo, who seems to have fallen out of favor with the group after becoming a government censor.

Born into a family of doctors and herbalists in the city of Wuxi, Zhang Guangyu left home at 14 to apprentice in a shop in nearby Shanghai, soon to be followed by his younger brothers, Zhang Meiyu 張美宇 (1902-1975)[11] and Zhang Zhengyu.[12] In his free time, Zhang met Zhang Yuguang張聿光 (from whom Zhang seems to have adapted his pen name) a set painter and make-up artist for the New Stage 新舞台, one of the first theatres in China to use Western lighting and sets to perform Chinese opera. Zhang Yuguang introduced Zhang Guangyu to his close friend Ding Song who was looking for an assistant to help out with the Shijie Huabao. One year later, Zhang Guangyu drew on this experience to partner with Yan Esheng 嚴鍔聲 and Qian Huafo 錢化佛 to publish the Comedy Pictorial 滑稽畫報, launched in October, 1919. Although Comedy Pictorial only lasted for two issues, it is notable for being Zhang’s first foray into publishing.

In 1921 Ding Song left the Shanghai Art Academy to work in the advertising department of Shanghai-based multinational British-American Tobacco 英美煙草公司. Zhang Guangyu also continued to move up in the world, finding full time employment as an artist for the Chinese-owned Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company南洋兄弟煙草公司in 1921, where he would work for the next four years. During this time he took advantage of his regular income to subsidize his various commercial and artistic ventures, the first of which was The Motion Picture Review 影戲雜誌, launched in December, 1921.[13] Zhang co-edited this 80-page long magazine along with the actor and filmmaker Gu Kenfu 顧肯夫 (? – 1932) and translator Lu Jie陸潔 (1894-1967). The first two issues were co-published by the Chinese Motion Picture Research Society中國影戲研究會, where Gu Kenfu worked, and the Motion Picture Review Press影戲雜誌出版社, while the third and final issue was published by Mingxing Film Company明星影片公司. Although it ultimately failed to take off, The Motion Picture Review also holds the distinction of being the first Chinese movie periodical, and Lu Jie’s reviews of foreign films are said to have had a major impact on the lexicon of film terminology in Chinese.[14]

It also gave Zhang Guangyu the practical experience necessary to launch the Oriental Fine Art Press東方美術印刷公司in 1923, although it is unclear what exactly this press was involved with printing or when or why it closed up shop. Never one to rest on his laurels, in 1924 Zhang co-founded the Chinese Art Photography Study Group中國美術攝影學會 with Ding Song and Lu Shaofei (among others), a move that would prove prescient for the would-be publishers.[15] Photographs would go on to form an important part of the Manhua Society’s members’ later publications, with artistic nudes proving to be a particularly popular feature.

Lu Shaofei: The Portraitist’s Son

Aside from Zhang Guangyu, Ding Song had a second student who decided to follow him into the profession that Shen Bochen had introduced him in the early 1910s. Born in 1903, Lu was the sole native Shanghainese of the Manhua Society, having grown up near the City God Temple in Nanshi where his father earned his living as folk portraitist. Encouraging his son to pursue a career as an artist from an early age, the family was able to scrape together enough from their meager earnings to send Lu to the Shanghai Art Academy, where he almost certainly would have studied under Ding Song. Unfortunately, the burden of tuition proved to be too high, so Lu was eventually forced to drop out.[16] His first cartoon in the Shenbao was published on October 17, 1921.

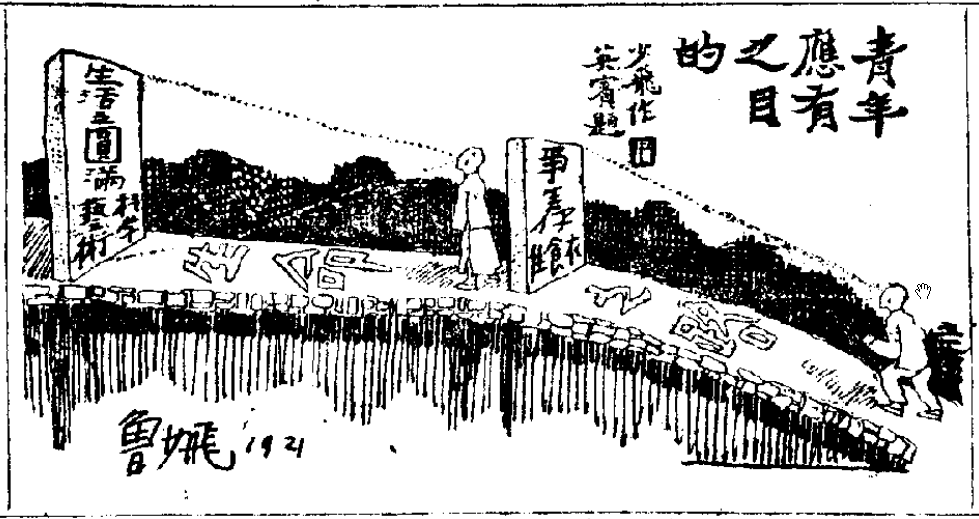

Titled “Goals the Youth Should Have” 青年應有之目的, it depicts a narrow raised path that slopes gently upwards, labeled “The Road of Life” 生命之路. Two walls block the way, the second significantly higher than the first. A young man is poised in mid stride in front of the first wall, with a dotted eye-line extending to wall, which is labeled “Fight for: shelter, food, and clothing” 爭奪 住食衣.

Figure 2.2 Lu Shaofei “Goals Youth Should Have” 青年應有之目的 Shenbao, October 17, 1921, 17.

A second youth stands just beyond this first wall, gazing up at the second, which is labeled “A Fulfilled Life: Art, Science” 生活之圓滿 藝術 科學. Unlike the first youth, who is dressed in pants and long sleeve shirt, the seconds wears a Chinese-style tunic and jacket, perhaps indicating that he has achieved a higher level of material wealth, or simply that he is older. The title of the cartoon is written in thick brush strokes in the top right hand corner, along with the words “A work by Lu, inscribed by Yingbin [Wang Yingbin汪英賓 (1897-1971)]” 少飛作英賓題, while in the lower left hand corner Lu has written his name and the year with a pen.

Two years later, in 1923, Lu Shaofei was hired to teach art at Liangjiang Women’s Physical Education Normal School 兩江女子體育師範學校.[17] Founded two years earlier in 1921[18] by Lu Lihua 陸禮華 (1900-1997), an early proponent of women’s liberation and physical fitness for strengthening the nation, the first class only had 17 students and was housed in a private residence on Dengnaotuo Road 鄧腦脫路. By the time Lu arrived, the school had over 100 students and was in the midst of expanding to include a middle school and elementary school, but the address had yet to change.[19] Lu taught at Liangjiang for over a year before moving on to the Oriental Art Professional School 東方藝術專門學校 in the French concession.

In 1924 Lu Shaofei was invited to teach Western-style art at the newly established Fengtian Art Academy 奉天美專 in Shenyang (then commonly referred to by its earlier Manchu name, Mukden). Founded that same year by Han Leran韓樂然 (1898-1947), Leran had secretly joined Chinese Communist Party after graduating from the Shanghai Art Academy in 1923.[20] While teaching in Shenyang, Lu began work on what would become Cartoon Travels in the North 北游漫畫. This book included sketches and cartoons dealing with his experiences living in Shenyang.[21] By February 1925, Lu had returned to Shanghai where he contributed art work to the famous stationary company Lianyi Trading Co. 聯益貿易公司.[22]

Continued in Chapter 3…

[1] Ye recalls that they met in 1926, while he was working at Central Plains Press. The first issue of Camera Daily News was published on August 2, 1925, and, reflecting the Chinese name of the paper [literally, ‘Three Day Pictorial’], was published every three days after that. Most likely, Ye got the dates mixed up, as he does in several other places in his autobiography.

[2] The surviving buildings of the orphanage have since been turned into a museum which recreates the original structure and showcases the art of its former teachers and students. At the time of operation “Tushanwan” was romanized “Tou-se-we” to represent the pronunciation in Shanghai dialect.

[3] From 1913-1920, the school was also sometimes referred to as Shanghai Tuhua Meishu Yuan上海圖畫美術院 (Shanghai Painting Academy of Fine Art). In 1920, when Liu Haisu 劉海粟 (1896-1994) took over as director from Zhang Yuguang, the name of the school was changed to Shanghai Meishu Xuexiao上海美術學校(Shanghai Fine Arts School). In 1930 it was changed again to Shanghai Meishu Zhuanke Xuexiao上海美術專科學校 (Shanghai Professional Fine Arts School). Today it is commonly referred to as Shanghai Meizhuan 上海美專, an abbreviation of the final name for the school before it was merged with Disi Zhongshan Daxue Jiaoyu Xueyuan (The Fourth Zhongshan University, Education Academy), becoming the Yishu Jiaoyu Zhuanxiu Ke藝術教育專修科 (Department of Art Education). See Michael Sullivan, Modern Chinese Artists: A Biographical Dictionary (University of California Press, 2006), xix and Shanghai Municipal Archives Q258-1-153, p. 0012 cited in Julia Frances Andrews, “Pictorial Shanghai (Shanghai Huabao, 1925-1933) and Creation of Shanghai’s Modern Visual Culture,” Journal of Art Studies no. 12 (September 2013): 43–128.

[4] Originally published as a supplement to The National Herald 神州日報 until being launched as a separate periodical in 1919, the first character of Chinese name of The Crystal, 晶 (literally ‘crystal’), is made up of the character for ‘day’ (or ‘sun’) 日 repeated three times, a play on the fact that the tabloid was printed every three days. See Sun Shusong 孫樹松 and Lin Ren 林人, eds., “Jin Bao” 晶報 [The Crystal], Modern Chinese Compilation Studies Dictionary 中國現代編輯學辭典 (Heilongjiang People’s Press 黑龍江人民出版社, 1991), 229.

[5] First issue September, 1913, second and last issue October, 1913. Originally published as supplement to the Shenbao under the name Unfettered Talk自由談 , two issues Unfettered Magazine were published by Shenbaoguan 申報館 before it returned as a supplement to the Shenbao (where some 15 years later it would feature Ji Xiaobo et. all’s Dr. Fix-it under the editorship of Zhou Shoujuan). Wu Jie 伍傑 et al., eds., Zhongwen qikan da cidian 中文期刊大詞典 [Dictionary of Chinese Periodicals] (北京大学出版社, 2000).

[6] John A. Crespi suggests that this cartoon is criticizing young men who dote on wealthy older women to achieve wealth and official status, a common subject of satire in China during the 1910s.

[7] Barmé, An Artistic Exile, 94.

[8] As translated by Geremie Barmé, with the exception of the two lines which I have changed: The first line has been amended to include the text “While [the artist Shen Bochen] draws in style which is copied from the West,“ [沈泊塵] 的畫法,倒也模仿西洋, which Barmé chose to omit; and the second line (which seems to be a typo on the part of Lu Xun) has been corrected from the translation “I’m so-and-so’s son.” See Ibid. and Lu Xun 魯迅, “Sishi-san” 四十三 [Essay Forty-Three], in Re Feng 熱風 (Beixin Shuju 北新書局, 1925), 39.

[9] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Shanghai Poke” 上海潑克 [Shanghai Puck], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 596. Shanghai Puck’s name was likely inspired by one or more pre-existing journals called Puck (in London, in St. Louis, and in New York). See Wu I-Wei, “Participating in Global Affairs: The Chinese Cartoon Monthly Shanghai Puck,” in Asian Punches: A Transcultural Affair, ed. Hans Harder (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013), 365–87. Also not to be confused with Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari, a late 19th century cartoon periodical modeled on the successful British humor magazine, Punch, or the London Charivari. Written in English by colonists living in the foreign concessions was published from April, 1871, to November, 1872. Christopher G. Rea points out, however, that, “[this] little-examined [magazine is a] milestones in the history of the cartoon in China, not because of their influence on Chinese cartoonists, but as the earliest known examples of how foreigners brought literary humour and pictorial satire to bear on colonial society in China.” See Christopher G. Rea, “‘He’ll Roast All Subjects That May Need the Roasting’: Puck and Mr Punch in Nineteenth-Century China,” in Asian Punches: A Transcultural Affair, ed. Hans Harder (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2013), 389–422.

[10] For more information on the Heavenly Horse Society, see Michael Sullivan’s entries on Liu Haisu劉海粟 (1896-1994) on page 99 of Modern Chinese Artists and page 45 of Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China (University of California Press, 1996).

[11] Better known as Cao Hanmei 曹涵美, the name he took after being adopted by a maternal uncle who was without male heirs. See Jiang Yihai 蔣義海, ed., “Cao Hanmei” 曹涵美 [Cao Hanmei], Manhua Zhishi Cidian 漫画知识辞典 (Nanjing Daxue Chubanshe 南京大学出版社, 1989), 337.

[12] Compared to his older brother, considerably less has been written about Zhang Zhengyu. After attending private school in Wuxi, Zhang spent some time as an apprentice in a flour mill before following Zhang to Shanghai in 1921. Only 17 years old, Zhang, like his brother before him, studied set design under Zhang Yuguang, eventually branching out in commercial art work. Although he does not seem to have published any cartoons until the late 1920s, he quickly emerged as an important and prolific cartoonist, also playing an important role behind the scenes at the various publications launched by Zhang Guangyu. Later in life he became known for his calligraphy and drawings of cats and pandas, influenced by traditional Chinese painting and seal carving. See Yihai Jiang 蔣義海, ed., “Zhang Zhengyu” 張正宇 [Zhang Zhengyu], Manhua Zhishi Cidian 漫畫知識辭典 (Nanjing Daxue Chubanshe 南京大學出版社, 1989), 211–12.

[13] Wang Guangxi 王廣西 and Zhou Guanwu 觀武 周, eds., “Yingxi Zazhi” 影戲雜志 [The Motion Picture Review], China Contemporary Literature and Art Dictionary 中國近現代文學藝術辭典 (Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Press 中州古籍出版社, 1998), 1112–13, Zhengzhou.

[14] The film scholar Wang Liu credits Lu Jie with having popularized the term daoyan 導演 (lit. “performance guide”) as a translation for “director,” among other film terminology that has since become standard. See Wang Liu 汪流, ed., “Lu Jie” 陸潔 [Lu Jie], Dictionary of Sino-Foreign Film and Television 中外影視大辭典 (Beijing: China Broadcast Television Press 中國廣播電視出版社, 2001), 311, Beijing.

[15] Other members of this group included Hu Boxiang胡伯翔 (who would later become a partner for Shanghai Sketch II), Ge Gongchen 戈公振, Wang Shouti 汪守惕 , Song Zhiqin 宋志欽, and Fu Yanchang 傅彥長. See “Tuanti Huiwen” 團體彙聞 [Organization News], Shenbao 申報, July 29, 1924, 20.

[16] Bao Limin 包立民, “Ye Qianyu yu Lu Shaofei (shang)” 叶浅予与鲁少飞(上) [Ye Qianyu and Lu Shaofei (Part I)], Meishu zhi you 美术之友 no. 02 (1994): 23.

[17] “Xuewu qianzai” 學務僉載 [School Affairs], Shenbao 申報, July 16, 1923.

[18] In an interview conducted 1993-1995, Lu recalled that the school was founded in 1922. A 1934 article by Lu, however, records that the school was founded in 1921. Lu recalls that the school had over 30 students in its second year, but continued to struggle financially until the beginning of its third year. Given that the Shenbao notice mentions that Lu Shaofei was one of ten new teachers being hired, the earlier date makes more sense. See Chapter 4 of Wang Zheng, Women in the Chinese Enlightenment: Oral and Textual Histories (University of California Press, 1999) and Lu Lihua 陸禮華, “Fuxing houde liangjiang nuzi tiyu shifan xuexiao shi nian qian de huisu” 復興後的兩江女子體育師範學校十年前的洄溯 [Recollections of the Since Rejuvenated Liangjiang Women’s Physical Education Institute of Ten Years Ago], Qinfen tiyu yuebao 勤奮體育月報 1, no. 10 (1934): 42–43. Chapter 3 of Yunxiang Gao’s Sporting Gender: Women Athletes and Celebrity-Making during China’s National Crisis, 1931-45 (UBC Press, 2013) is also dedicated to Lu Lihua and her school.

[19] In 1937 the school changed names, becoming Shanghai Shili Tiyu Zhuanke Xuexiao上海市立體育專科學校 (Shanghai Municipal Physical Education Professional School).

[20] Shen Guangjie 沈廣傑, “Han Leran chuangban Fengtian Meizhuan” 韩乐然创办奉天美专 [The Founding of Fengtian Art Academy by Han Leran], Dangshi Zongheng 黨史縱橫 no. 05 (2012): 49–50.

[21] Although Bi and Huang record that the first edition of Cartoon Travels in the North was published in 1924 or 1925 while Lu was living in Shenyang, the fact that the title includes the term ‘manhua’ is suspicious, given that the term did not become popular in China until the publication of Feng Zikai’s illustrations were published under that name in May, 1925. The earliest definitive date for publication is three years later in Shanghai on May 15, 1928. See Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Beiyou Manhua” 北游漫画 [Cartoon Travels in the North], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷 (Shanxi Renmin Meishu Chubanshe 陝西人民美術出版社, November 2000), 651–52.

[22] “Lianyi Jian Si Ban Faxing” 聯益箋四版發行 [Fourth Printing of Lianyi Stationary], Shenbao 申報, February 27, 1925, 19.