The Tiananmen Square Massacre is an incredibly difficult topic to discuss without getting smeared with the brush of anti-CCP demagogue or, alternately, pro-CCP apologist. The modern Chinese historian Jeff Wasserstrom has argued that the term “Tiananmen Square Massacre” itself is something of a misnomer, given that most sources seems to agree that most (if not all) deaths occurred in the streets of Beijing rather than the square itself. Perhaps for this reason, the Chinese term is the much more neutral 6/4 六四, not unlike 9/11 in English. Meanwhile the iconic image of the Tank Man, together with student leader Chai Ling’s 柴玲 heart-rending (albeit unsubstantiated) account of seeing students flattened by tanks in the Square, has overshadowed the much more numerous deaths caused by PLA gunfire. Equally critical, is the fact that workers and inhabitants of Beijing stood up and were killed along with the students, and that Beijing wasn’t the only city which experienced massive unrest: Shanghai experienced worker strikes and student walkouts, as did Wuhan, Guangzhou, Xi’an, Nanjing, Chengdu, and likely other cities as well.

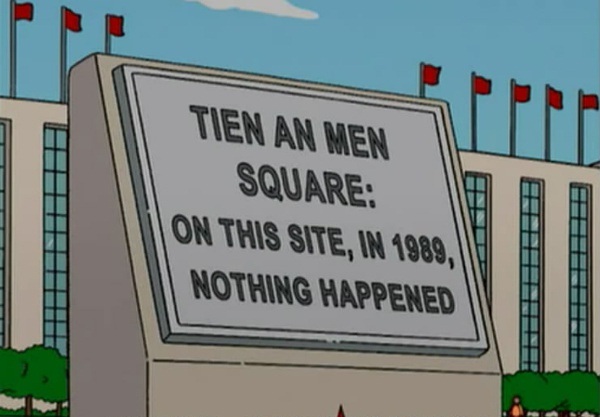

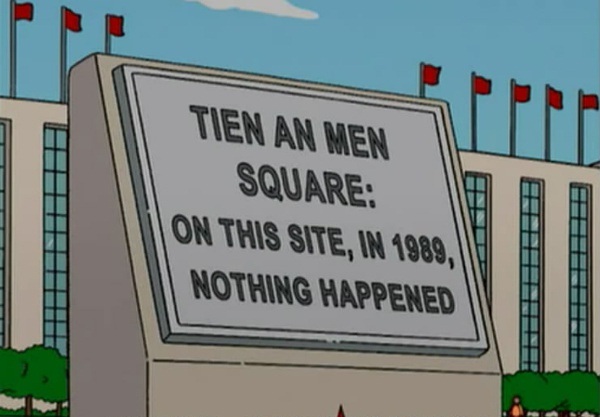

Unsurprisingly, the protests and crackdown remain sensitive topics in the PRC even today. More surreal, perhaps, is the fact that many younger Chinese know almost nothing about them and those that do often have little interest in discussing them:

Simpsons Episode 12 “Goo Goo Gai Pan,” Season 16, aired March 13, 2005.

This contrasts starkly with the situation abroad, where China is perhaps best known for the events of June 4, 1989. As a student of modern Chinese cultural history I find myself intensely conflicted about talking about 6/4. On the one hand, as a historian, I recognize that history should be a neutral, “true record” of events as they actually occurred, something which often conflicts with the desires of nation states and political parties to paint their pasts in the brightest colors possible.

On the other hand, as someone who is passionate about Chinese literature and culture, I often find myself frustrated with the extent to which the discourse on China is dominated by 6/4. Chinese literature in translation, in particular, seems to be almost singularly restricted to works which are “banned in China.” This leads to a very skewed perspective on Chinese popular culture in North America, which is in many ways every bit as vibrant (and trashy) as popular culture anywhere else in the world. Romance, horror, mystery, and sci-fi are all thriving, both on the internet and in bookstores. And even “serious literature” is thriving, too: two of the most popular novels in translation are 1984 and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

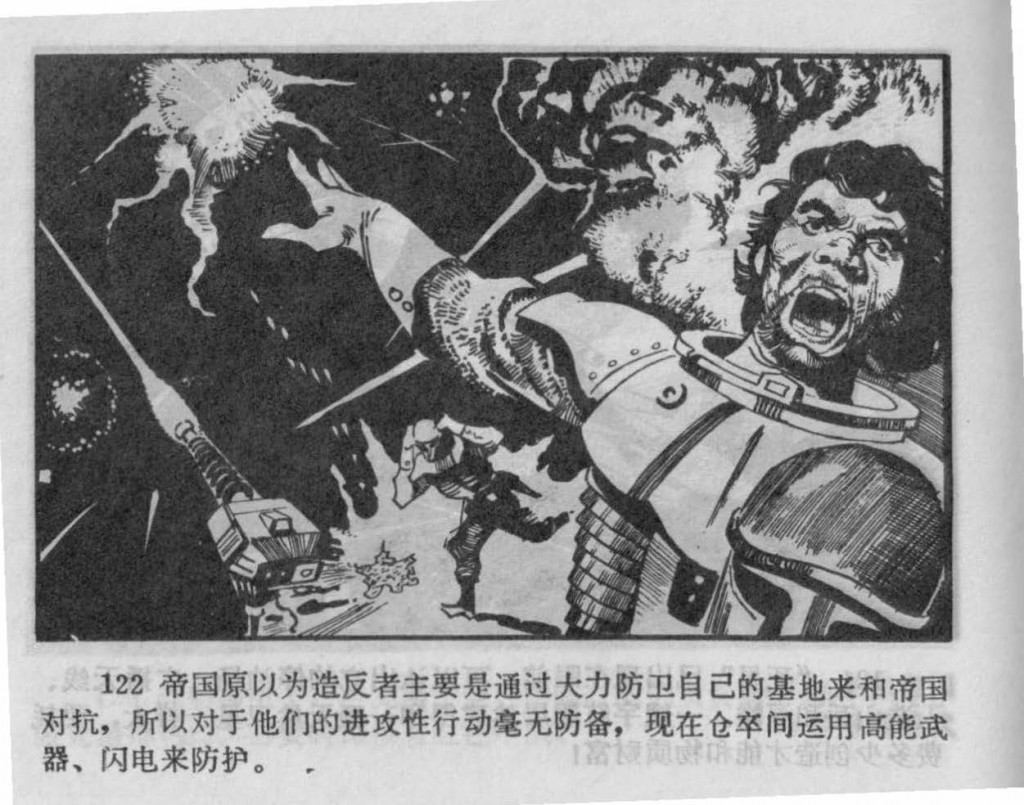

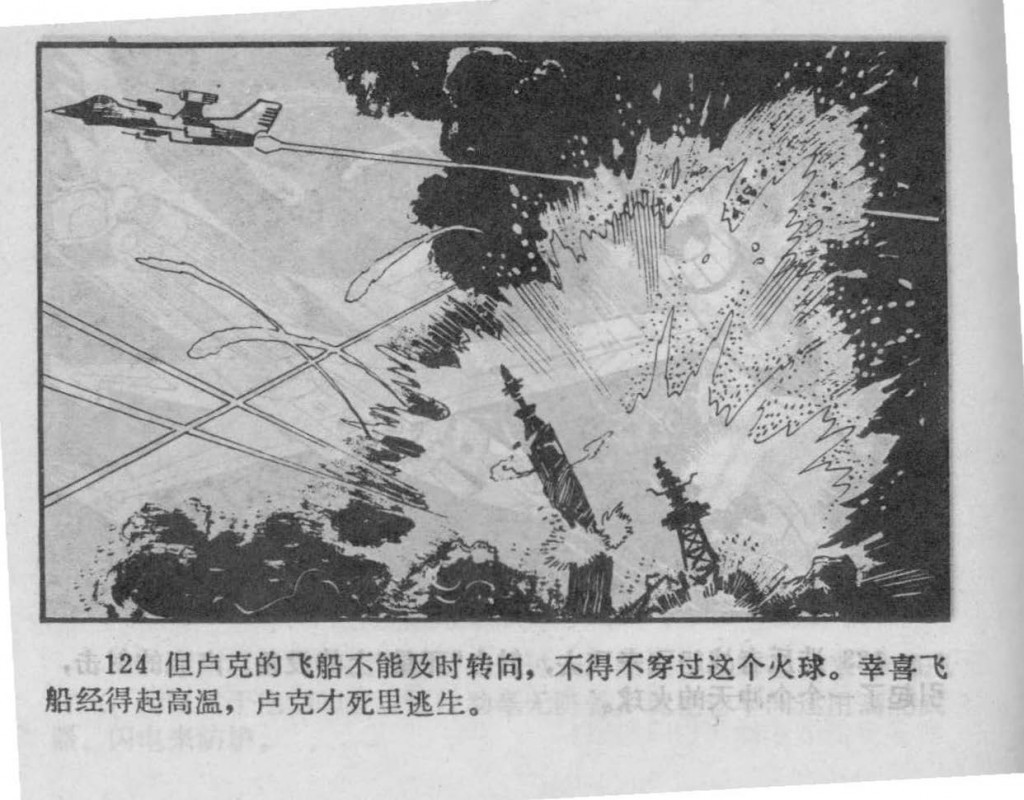

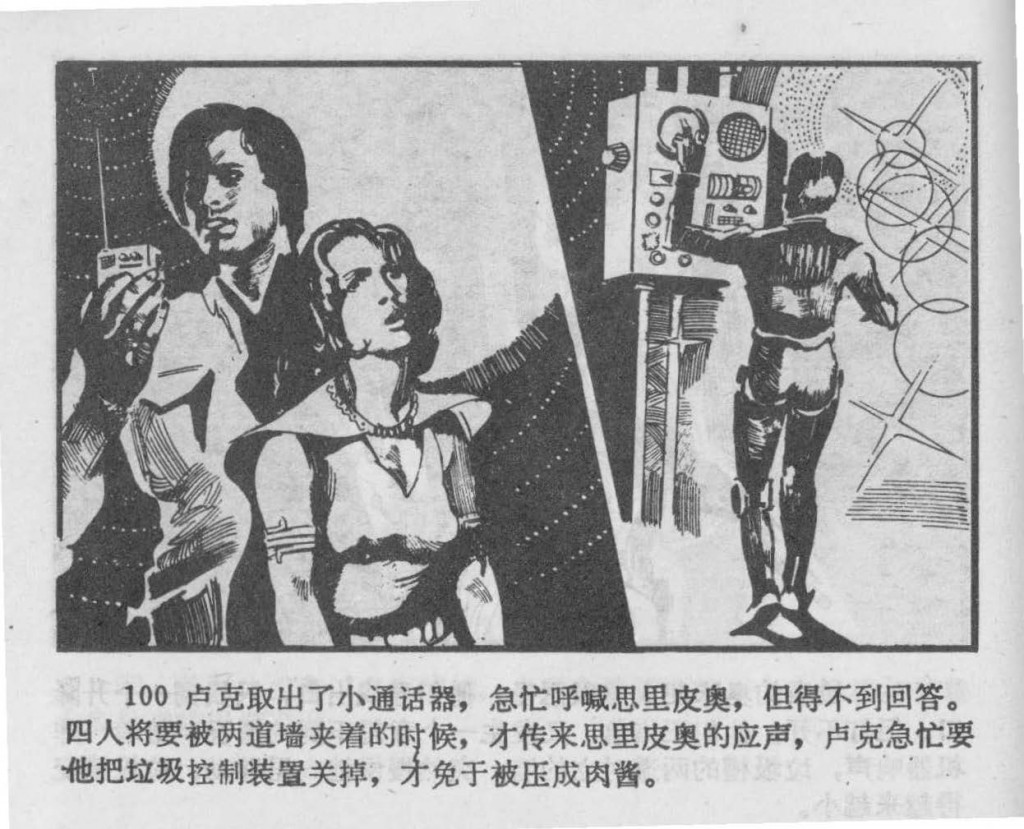

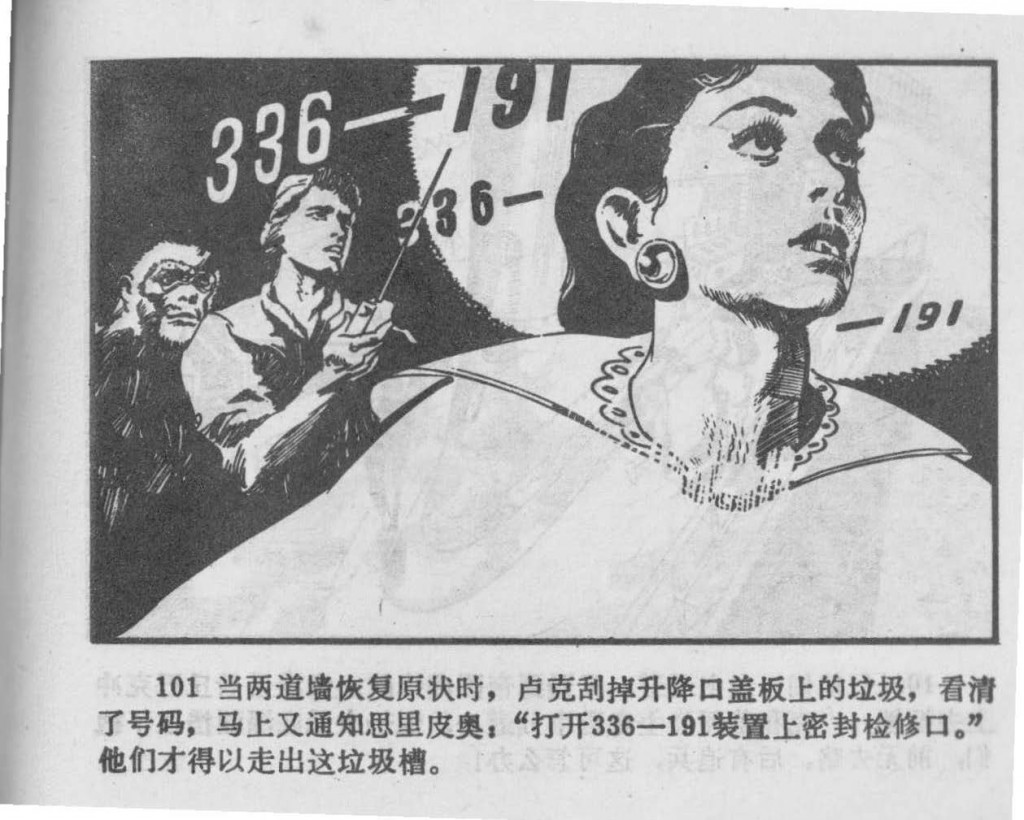

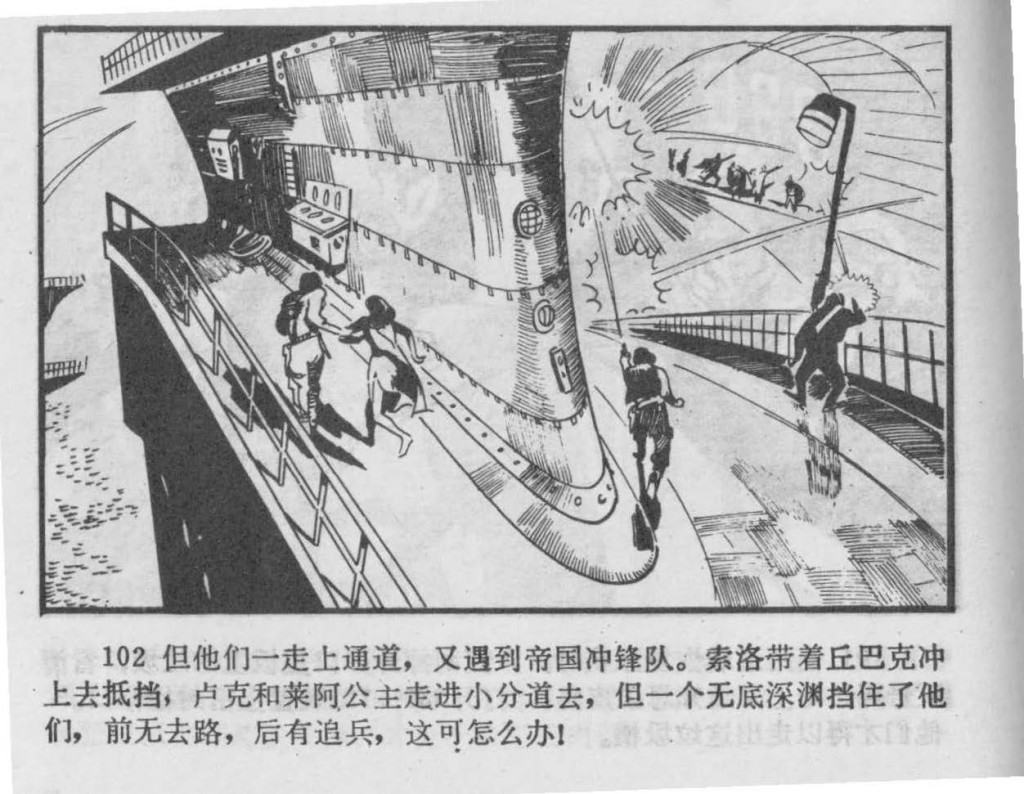

And as Maggie Greene points out in her recent post on the surprisingly warm reception her Star Wars comic received on the internet last week, there have been other, earlier periods of “thaw” in censorship, particularly during early 1960s following the Great Leap Forward, and again in the 1980s, after the Cultural Revolution.

I think this is a much larger issue than just 6/4, one which can be traced back to Cold War. The communist takeover of China and the polarizing figure of Chairman Mao perhaps irrevocably connected China with socialist and totalitarian politics in the American imagination. Theodore H. White’s 1967 Emmy-winning documentary, China: The Roots of Madness is emblematic of this association, and of the desire to connect the man-made tragedies of the Mao-era with earlier cultural traditions in China:

While the desire to understand the madness of the Cultural Revolution is understandable, blaming the excesses of radical Maoism on 2000 years [sic] of Confucianism is a little bit like saying McCarthyism was caused by the same Puritanical-thinking which led to the Salem witch trials. And while it might seem like this kind of thinking is far behind us, consider the the widespread belief that China isn’t “ready” for democracy or that Chinese people are incapable of creativity.

That said, there are many accounts of 6/4 which do an excellent job of placing it in a larger historical context. I personally think autobiographical comics and animations are well suited to this purpose. Memory is incredibly subjective, and photographs have a tendency to seem much more objective than they often actually are. When we look at a drawing of a memory we are forced to acknowledge that memories are created and re-created over and over, rather than being preserved like fossils waiting to be unearthed.

1. Wang Shuibo’s 王水泊 Sunrise Over Tiananmen Square 天安門上太陽升

The visceral sense of the betrayal Wang Shuibo experienced after 6/4, having grown up in a “New China” where Mao was treated as essentially a demi-god and the CCP were his sacred protectors is palpable in Wang’s 1998 Academy Award nominated short animated film . This is something I have seen first-hand among my Chinese friends who seem to be angrier about the fact that the government continues to lie to them about the past than they do about the massacre itself, the impact of which has faded somewhat with the passage of time:

. This is something I have seen first-hand among my Chinese friends who seem to be angrier about the fact that the government continues to lie to them about the past than they do about the massacre itself, the impact of which has faded somewhat with the passage of time:

Continue reading →