Firsts are always controversial. If the first Chinese cartoonist was the student of another, earlier cartoonist or proto-cartoonist, either by instruction or by inspiration, then he wasn’t really the first Chinese cartoonist, was he?

In a way, it all depends on how broadly or narrowly you choose to define the word “cartoon,” or kǎtōng 卡通 or “comics” mànhuà 漫畫 in Chinese. Strictly speaking, the first time the word “manhua” was used to describe a cartoon-like drawing by a Chinese artist occurred when Zheng Zhenduo 鄭振鐸 published drawings by Feng Zikai 豐子愷 under that name in the periodical Literature Weekly 文學周刊 in 1925. Most scholars agree however that Feng’s work represents a synthesis of earlier works. Geremie R. Barmé, for example, has found particularly strong stylistic and thematic resemblances to the popular Japanese artist Takehisa Yumeji 竹久夢二 (1884-1934) whose work Feng was exposed to while studying abroad for 10 months in 1921.1

Chinese scholars Bi Keguan 畢克官 and Huang Yuanlin 黃遠林, meanwhile, have “[traced] a genealogy back to such pre-modern proto-cartoons as stone etchings (shike 石刻) from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE) and humorous brush paintings from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).”2 These stone etchings were likely based on earlier works in more ephemeral media, like wood or paper, which themselves would have found inspiration in the oral tradition.

In short, it’s cartoonists all the way down.

More importantly, perhaps, as Tom Gunning points out in his landmark essay on “the first” fictional and comedic film (the Lumiere brothers’ L’Arroseur arrosé), the whole process of arguing over who is standing on whose shoulders can get in the way of looking at things which really matter, or as he puts it, “the issues history involves.” Even so, Gunning makes a good argument for paying attention to so-called “firsts” not so much out of respect for their chronological precedence, but instead to consider the ways in which they set a precedent for works yet to come:

“Firsts” are the bane of film history. Not only are they usually dubious (given how many films have disappeared), they also obscure the issues history involves. If this Lumiere film has a significance for the history and theory of film comedy…that significance comes precisely from the films that came after it, from the way it set up a widely imitated prototype.3

In this spirit, I think a strong argument can be made that it was not until the last decade of the 18th century that works which meaningfully anticipate manhua began to emerge, and that moreover the most influential “cartoonist” during this time period was the mysterious Wu Youru 吳友如 (1841-5?-1893?), one the most prolific “newspainters” of the late-Qing who created illustrations for the Dianshizhai Pictorial 點石齋畫報, published by the British entrepreneur Ernest Major’s 美查 Dianshizhai lithographic press4 in Shanghai from May 8, 1884, to August 16, 1898.5

Very little is known about Wu, aside from a few scattered biographical sketches of dubious authenticity penned by his admirers. Rudolf G. Wagner has painstakingly sorted through the scant evidence which exists to create a rough sketch of his life and times, providing at long last a credible source of information: a short autobiographical note in the Feiyinge huace xiaoqi 飛影閣畫冊小啟, published in 1893.6 Born in Suzhou, Wu claimed to have been something of a playboy in his youth, having spent his family fortune on idle pastimes. Forced to flee to Shanghai during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), he arrived in Shanghai at the age of 20 where he eventually found success as an illustrator for the emerging lithographic print industry.

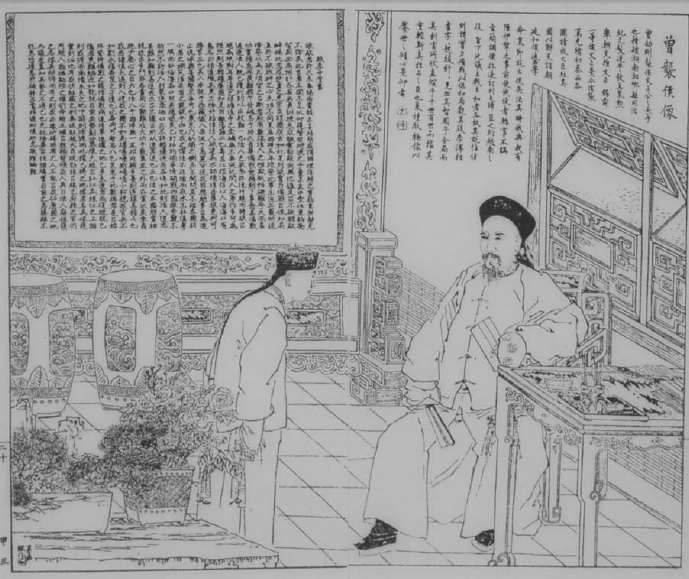

Wu Youru, “Portrait of Zeng Jize.” Dianshizhai Pictorial, May 27, 1884. Source: Wagner, p. 137.

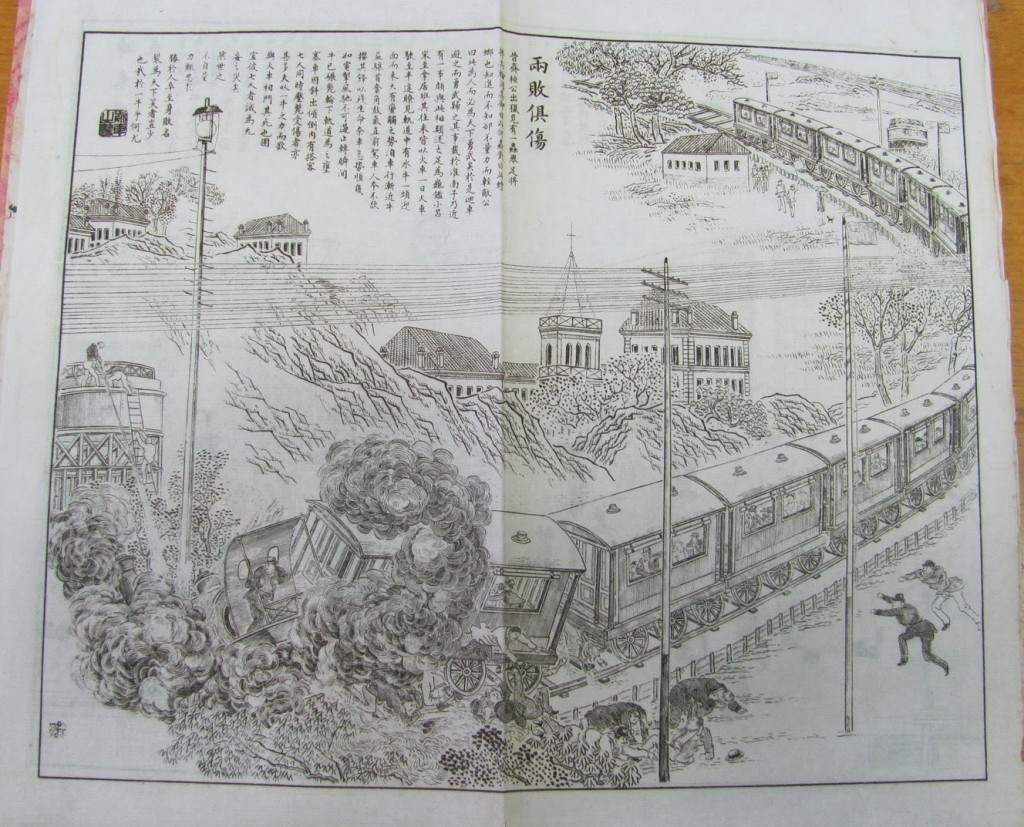

Lithographic printing represented a enormous technological innovation for Chinese publishers (and, more often than not, foreigners looking to publish in Chinese). More durable than metal engraving, and more less technically challenging than the wood engraving pioneered by Thomas Bewick and perfected by illustrators working for English publications such as the Illustrated London News, lithography allowed Chinese text and images to be juxtaposed seemlessly:

Wu Youru, Feiyingge Huabao. September 1890 Source: D.B. Dowd, “News From Abroad: Trainwreck!,” Graphic Tales

Certainly, there are many other artists who were as, if not more capable, who also were working as newspainters at the time, and it is even possible that there are nianhua 年華, or New Year’s Print artists working with woodblocks who were more prolific, or at least saw a wider distribution. Liu Mingjie 劉明杰 (1857-1911) is a especially interesting example of a sui generis newspainter who created woodblock prints of the Boxer Uprising and the siege of the Legations in Beijing. Although these works were once thought to only have survived in oral traditional, the nianhua scholar James A. Flath discovered that one had managed to find its way into the collection of the Yale Divinity School:7

As translated by Flath, the text accompanying this image reads in part:

Beat the drum, sound the bugle,

Dong Fuxiang, proud in character,8

Leading men and horses, shouldering a gun,

At the vanguard are the Boxers,

Marching behind are the Red Lanterns,9

Beat them well, beat them good,

The vanquished devils’ attack breaks down,

Bright red cap on top of your head,

Of all the officials under heaven, you are the best.10

Likewise, a infamous set of anti-Christian woodblock prints published under the (rather awesome) title Heresy Exposed In Respectful Obedience To The Sacred Edict: A Complete Picture Gallery 謹遵聖諭辟邪全圖, were published at some point in the second-half of the 19th century, reputedly commissioned by Zhou Han 周漢 (1842-1911), a literati who had been given the official post of daotai 道台in his hometown of Ningxiang County, Hunan, for his military service during the tumultuous Taiping Rebellion:11

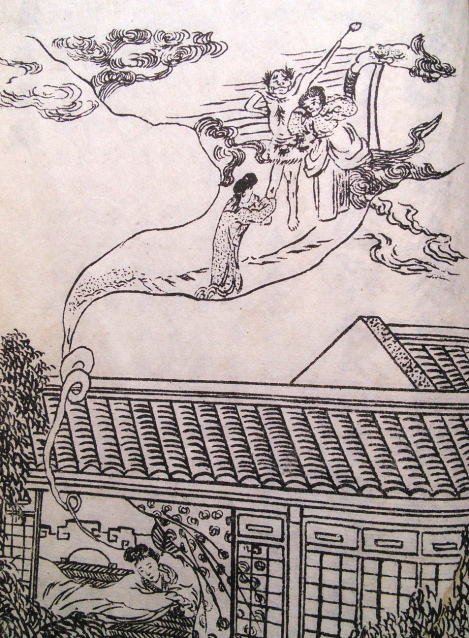

“Beating the [Foreign] Devils and Burning Their Books” Source: John, 1891.

The text of this image reads:

The depraved religion of the Hog (Jesus) is propagated from foreign lands. Its followers insult heaven and exterminate ancestors; ten thousand arrows and a thousand swords (the severest punishments) would not expiate their crimes…Their dog-fart magical books stink like dung; they slander the holy men and sages; they vilify the [Taoist] Genii and Buddhas; all the Nine Provinces and the Four Seas hate them most intensely.12

Such proto-cartoons may well represent some of the earliest prototypes for the artist as an entrepreneur, which represents a clear break from the traditions of literati and academic painting which date back to at least the Six Dynasties.13 More importantly, these artists helped pave the way for the development of a mature manhua periodical industry in Shanghai and other entrepôt cities the late 1920s and up until the Japanese invasion of 1937. Still, in subject matter and style, I think a more clear lineage exists between Wu Youru and artists such as Zhang Guangyu 張光宇, and Ye Qianyu 葉浅予, who would have grown up surrounded by Wu’s art and copycats thereof:

Page from the 1936 edition Yu Zhi’s Illustrated Stories of Twenty Four Filial Women, (almost certainly falsely) attributed to Wu Youru

Source: Katherine Alexander “Filial modern women buy our towels!” Far From Formosa

- Geremie Barmé, An Artistic Exile: A Life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975) (University of California Press, 2002), pp. 52–71. [↩]

- Christopher Rea, ‘He’ll Roast All Subjects That May Need the Roasting’, in Asian Punches – A Transcultural Affair, ed. by Hans Harder and Barbara Mittler, pp. 389–422 (p. 392); Keguan Bi [毕克官], 黄远林 and Yuanlin Huang, Zhongguo manhua shi 中國漫畫史 [A History of Manhua in China] (Beijing: Wenhua yishu chubanshe, 1986), Beijing. [↩]

- Tom Gunning, ‘Crazy Machines in the Garden of Forking Paths: Mischief Gags and the Origins of American Film Comedy’, in Classical Hollywood Comedy, ed. by Kristine Brunovska Karnick and Henry Jenkins (New York: Routledge, 1995), pp. 87–105 (p. 88). [↩]

- itself a part of the larger press, Shenbaoguan 申報館, responsible for the first newspaper in China, the Shenbao 申報 [↩]

- Wagner, Rudolf G., ‘Joining the Global Imaginaire’, in Joining the Global Public: Word, Image, and City in Early Chinese Newspapers, 1870-1910 (SUNY Press, 2012), p. 131. It should be noted that Ernest Major himself left Shanghai in 1889, at which time the Shenbaoguan, and the Dianshizhai along with it, came under new management. Wu Youru left the press around the same time to start his own illustrated periodical, the Feiyingge Pictorial 飛影閣畫報. [↩]

- See Wagner, p. 126-127 [↩]

- James A. Flath, The Cult of Happiness: Nianhua, Art, and History in Rural North China (UBC Press, 2011), p. 103. [↩]

- Dong Fuxiang董福祥 (1839–1908), commander of a mixed army of Han and Hui [Chinese Muslim] troops from Gansu, known to the West as the “Kansu Braves.” See Jonathan N. Lipman, ‘Ethnicity and Politics in Republican China: The Ma Family Warlords of Gansu’, Modern China, 10 (1984), 285–316 (p. 296). [↩]

- Female boxers were known as “Red Lanterns” and were said to have the power of flight, among other supernatural abilities. [↩]

- Flath, pp. 108–109; Zheng Jinlan [鄭金蘭], Weifang nianhua yanjiu 潍坊年畫研究 [Research on Weifang Nianhua] (Xuelin chubanshe, 1991), p. 108. [↩]

- Fun fact: Zhou was promoted his post by the scholar-general Zuo Zongtang左宗棠 whose name has been preserved for posterity by Chinese restaurants across North America which sell “General Tso’s Chicken.” [↩]

- The Cause of the Riots in the Yangtse Valley. A ‘Complete Picture Gallery.’, trans. by Griffith John (Hangkow: Hangkow Missionary Press, 1891), Hangkow. See also Peter C. Perdue, ‘Introduction to “The Cause of the Riots in the Yangtse Valley. A Complete Picture Gallery.”’, MIT Visualizing Cultures <http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/cause_of_the_riots/cr_intro.html>; ‘Zhou Han fan yang jiao an’ 周汉反洋教案 [The Case of Zhou Han Opposing the Foreign Religion] <http://www.changsha.cn/infomation/rllsfy/t20030808_1576.htm> . [↩]

- For more on these two school see R. Eno’s brief introduction here. [↩]

Pingback: Wu Youru: The “First” Chinese Cartoonist – Nick Stember | CleverJots

Pingback: Kultursöndag 31 augusti « VÄRLDENS FOLKRIKASTE LAND