This is the sixth chapter in my MA thesis, The Shanghai Manhua Society: A History of Early Chinese Cartoonists, 1918-1938, completed in December 2015 at the Department of Asian Studies at UBC. Since passing my defense, I’ve decided to put the whole thing up online so that my research will be available to the rest of the world. I’ve also decided to use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can share it with anyone you like, as long as you don’t charge money for it. Over the next couple of days I’ll be putting up the whole thing, chapter by chapter. You can also download a PDF version here.

Over the years which followed its founding in 1926, the Manhua Society would come to be seen as forming an important part of the history of cartooning in China. Writing in the English language magazine ASIA Monthly some eight months after the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War in May, 1938, Jack Chen described the fate of the Manhua Society in vivid language:

Since this was not a fair weather art, it did not attract those in search of fame or fortune. On the contrary, it offered poverty and hard knocks. The history of the first group of cartoonists is typical. Out of ten members, one died with enough money to pay for his funeral; one joined the government and secured a job that kept him from doing embarrassing cartoons, one disappeared after publishing a particularly pointed anti-Kuomintang cartoon, six managed to hold together, to be joined by a seventh who had been in hiding for four years during the bitterest persecution of Leftists: after the fall of the Wuhan government in 1927 and the split of the united front between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang. Their survivors met [in 1934] at the home of their dead friend, whither that all unknowingly come on the same mission–to give him a regular funeral. Of the seven, three had steady jobs that paid fifty dollars gold a month, and they earned perhaps fifty more by extra work. These are the best paid cartoonists in China. The rest scrape along as best they can, editing, teaching, doing odd jobs. And yet–making cartoon history.[1]

While it is easy to identify the first Manhua Society member mentioned as Huang Wennong, who died of ruptured stomach ulcer on June 21, 1934, the others are less obvious. Clearly, Ji Xiaobo is the most likely candidate for having joined the government, and the six who held together most likely refers to Ye Qianyu, Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhengyu, Lu Shaofei, Ding Song, and Hu Xuguang or Zhang Meisun. Huang Wang seems to have been the only out-and-out leftist in the group, although the dates for going into hiding seem wrong, since he was active throughout 1927 and early 1928, and again in 1930, with a four year period of inactivity from 1931 to 1934. This corresponds with the crackdown against the League of Left-Wing writers, of which he was a member, in February, 1931. The author of the pointed anti-KMT cartoon is more difficult to identify, but it may have been a younger member of the staff at Shanghai Sketch II, such as Xuan Wenjie, or someone less directly connected, such as Huang Shiying.

Birth of the Modern

Riding high on their success, on October 10, 1929, Shanghai Sketch Press 上海漫畫社, Zhang Zhengyu convinced his older brother to rename their press the China Fine Arts Periodical Press 中國美術刋行社and launch a second periodical, the monthly pictorial Modern Miscellany 時代畫報, to be co-edited by Zhang, and the modernist writer, Ye Lingfeng 葉靈鳳 (1905-1975).[2] Designed to compete with the wildly successful pictorial Young Companion 良友畫報, the inspiration for Modern Miscellany came after the Singaporean distributer for both Shanghai Sketch and Young Companion lost distribution rights to the latter. The distributor’s representative in Shanghai, Wang Shuyang (who had met Ye in 1925, when he interviewed him for the job at Three Friends Co.), approached Ye Qianyu and Zhang Zhengyu with this business opportunity, and Zhang managed to convince his older brother against of the urgings of their three partners. Shortly thereafter, Lang Jingshan, Hu Boxiang, and Zhang Zhenhou withdrew from the partnership in protest, forcing them to move their office from the church to an alley near the intersection of Nanjing Road and Zhejiang Road, just minutes from the Bund.[3]

As a result, the second issue of Modern Miscellany was delayed until late February of the next year, and the third issue was not published until May. To solve their cash flow problems, Zhang Guangyu and company announced in the June 7, 1930, issue of Shanghai Sketch that the publication would be merging with Modern Miscellany and the publication schedule changed to bimonthly.[4] On June 16, 1930, the first merged issue of Shanghai Sketch and Modern Miscellany was published, with the title shortened to Modern 時代.[5]

Meanwhile, in 1930 Ji Xiaobo and Ye Qianyu seem to have made steps toward burying the hatchet when Ji Xiaobo convinced the owner of Chenbao 晨報 [Morning Post] to launch a pictorial supplement which would serialize Ye Qianyu’s popular cartoon, Mr. Wang. Despite already working full-time as an editor at the bimonthly Modern Miscellany, Ye agreed, receiving 100 yuan per month for his strips, and two pin-up advertisements which the publisher requested in exchange for publishing the cartoon.[6] Despite Jack Chen’s sarcastic comment in late 1938 that “[Ji Xiaobo] joined the government and secured a job that kept him from doing embarrassing cartoons,” then, it seems possible that Manhua Society parted amicably, having served its purpose of launching the careers of its members.

Publication problems with Modern continued to persist, but as luck would have it, China Fine Arts Periodical Press had attracted the attention of the wealthy socialite and erstwhile poet, Shao Xunmei 邵洵美 (1906-1968), who was looking for an investment to change the declining fortunes of his large and profligate family.[7] In November, 1930 he officially joined the editorial staff of Modern, providing the necessary capital to have the magazine printed on the latest rotogravure presses rather than relying on the outdated copperplate etching that they had been using before.[8] A notice in Modern Issue 12 (Vol 1) announced

Improvement in Printing and Picture Plates

Starting with Issue 1, Vol. 2, we will begin using photogravure, plus two-color plates, three-color plates, seven-color plates, etc. The paper we use will also be changed to specially produced foreign-made photogravure paper, in what could be called a pioneering step in China.

印刷及圖版之改良

從二卷一期起改用影寫版印行並添加 雙色版、三色版、七色版等, 紙張亦改用特向外洋定造之影寫版專用紙, 可稱國內獨步[9]

As promised, the next issue of Modern, published on November 16, 1930, featured a large number of photographs, with much better contrast and fine detail. Over the next year however, due to the limited number of rotogravure presses in Shanghai at the time, Modern continued to suffer from delays, and quality declined as well. Finally, in the summer of 1931, Shao Xunmei managed to buy his own German-made rotogravure press for $50,000 US dollars, which was to be the foundation of his new venture, the Modern Press 時代印刷公司, and in the sixth issue (Vol. 2) of Modern, China Fine Arts Periodical Press announced that they would be taking a two month hiatus to set up their new press.[10] Renting a factory on Pingliang Road 平涼路in Yangpu district, between the Japanese controlled Hongkou district and the Huangpu River, Shao soon found himself cut off from his investment when this part of the International Settlement was occupied by Japanese troops arriving via gunboat in January, 1932.[11]

Figure 6.1 Logo of the Modern Press 時代印刷有限公司 designed by Zhang Guangyu in 1931.[12]

At the time, Hongkou was known as “Little Japan,” due to its large number of Japanese residents who moved to the district following the establishment of a Japanese consulate there in 1873. In 1876, Japanese residents of Hongkou built a Buddhist temple in the district, further solidifying its status as a de facto Japanese concession.[13] Directly to the north and west of Hongkou, meanwhile, lay the Chinese district of Zhabei. Containing the terminus to the Shanghai-Nanjing Railway, Zhabei proved to be an attractive location for industrialists, with one of the largest Chinese publishers, the Commercial Press, choosing to build their sprawling 80 acre campus there in 1907. By 1930, 29% of printing presses in Shanghai were based in Zhabei district, in addition to 42.6% of textile manufactures, 23% of the chemical industry, 22.4% of the food industry, and 16% of electromechanical manufacturers.[14]

On September 18, 1931 an explosion occurred near an important South Manchuria Railway line in the northeastern Chinese city of Shenyang. Later revealed to have been orchestrated by Japanese soldiers, the confusion provided the Kwantung Army with the necessary casus belli to order an invasion of Manchuria, claiming it was necessary for the protection of Japanese economic interests in the region. Ongoing Chinese boycotts of Japanese goods, in particular cotton, had been making it increasingly difficult for Japanese industrialists to operate in China, even with the protections afforded to them by numerous territorial concessions granted first by the Qing and later by successive warlord governments. Although Manchuria had been under the control of the Japanese-backed Fengtian clique for over two decades, economic collapse due to military overspending had left the clique weakened and unable to stand up against Chiang Kai-shek’s 蔣介石 Northern Expedition 北伐 of 1926-1928. Frustrated that their interests in Northern China were not being protected, the Imperial Japanese Army assassinated the leader of the Fengtian clique, Zhang Zuolin, later staging the “attack” in Shenyang when his son, Zhang Xueliang, surprised the world by pledging support to Chiang Kaishek and the Nationalists.

As Manhua Society founding member Wang Dunqing explained six years later, in 1937, during the politicized period of the Second Sino-Japanese War (and in a strident paraphrase by noted anti-imperialist and leftist, Jack Chen), the outrage created by this conspiracy was integral to the formation of manhua periodicals:

…the one event which had done the most to develop cartooning in China was the “Manchurian incident.” This was a tragic farce in the grand manner. Adequate comment on it was only possible in the form of caricature. For it meant simply that a vast territory containing thirty million people was occupied because a rail and two sleepers had been damaged by a grenade. The young revolutionary students reacted to this politically in their demonstrations, artistically in their cartoons. [15]

The Mukden Incident occurred during a general boycott of Japanese goods that had begun in July, 1931, following the Wanpaoshan Incident, in which Chinese farmers had clashed with Korean immigrants in Manchuria, leading to violent anti-Chinese riots in Korea (at the time under Japanese colonial rule) and Japan.[16] Although by no means the first anti-Japanese boycott, with strikes and protests ongoing from the May 30 Incident of 1925, it was the first to gain the overt support of the KMT government. The Mukden Incident in the fall added fuel to the fire of anti-Japanese sentiment, and by the end of the year it was estimated Japanese imports to China had declined by nearly a quarter.[17] In Shanghai, the boycott was particularly fierce, with Time magazine providing the following account from October, 1931:

In Shanghai such sniveling, furtive Chinese storekeepers as dared to offer Japanese goods for sale last week were roughly pounced upon by Chinese “police” of the self-appointed Anti-Japan Association and locked up in improvised jails. Gibbering with terror, the unpatriotic storekeepers were flung prostrate on the floor before Anti-Japan Association “judges,” kowtowing and howling for mercy. The “judges” imposed and actually collected “fines” up to $10,000 Mex. ($2,500) for the “crime” of selling Japanese goods. Convicted shopkeepers who said they could not pay were kicked back into Anti-Japan Association jails, kept there on persuasive starvation rations. This queer kind of justice, flagrantly illegal in every way, was everywhere upheld by Chinese public opinion, the opinion of one-fourth of mankind.[18]

On January 18, 1932, a protest by Japanese Buddhist monks against the Chinese boycott was staged outside the main Three Friends Co. factory in Zhabei. According to later accounts, to create an incident, a Japanese intelligence officer by the name of Ryukichi Tanaka 田中隆吉(1896-1972) hired local Chinese thugs to attack the monks, one of whom died of his injuries. Two days later, a Japanese paramilitary group burned down two buildings at the Three Friends factory in retaliation. Meanwhile, Japanese residents of Shanghai were petitioning their government for military intervention, and the Japanese military began demanding that the mayor of Shanghai, Wu Tiecheng 吳鐵城 (1888-1953), oversee the suppression of anti-Japanese groups in Shanghai. Despite the mayor’s capitulation, the situation continued to escalate. Japanese residents were evacuated and the Japanese navy began to send marines into Hongkou where they were stationed in a local park. On the evening of January 28, 1932, the Japanese marines launched an offensive into Zhabei from their base in Hongkou, ostensibly to rescue Japanese residents still trapped in Zhabei, where they clashed with the 19th Route Army of the NRA. Originally from Canton, they had been stationed in the city by Sun Fo and Chiang Kai-shek to protect Chinese interests, but few expected them to last long in the face of the Japanese assault.[19] In response to the surprisingly fierce resistance put up by the 19th Route Army, the Japanese military employed heavy aerial bombing and artillery shelling which was to destroy some 80% of the structures in Zhabei, including some 896 factories.[20]

Due to the turmoil of the so-called “Shanghai Incident” of 1932, which was concluded with a truce on March 3, the seventh issue (Vol. 2) of Modern did not come out until June, 1932, some ten months after the previous issue. Three months later, under Shao Xumei’s influence, China Fine Arts Periodical Press launched a new literary magazine, The Analects Fortnightly 論語半月刊, edited by the popular writer Lin Yutang 林語堂 (1895-1976). Lin Yutang was known for his advocacy of the use of humor to save the Chinese nation from totalitarianism, writing in 1937,

It seems to me that the worst comment on dictatorships is that presidents of democracies can laugh, while dictators always look so serious—with a protruding jaw, a determined chin, and a pouched lower lip, as if they were doing something terribly important and the world could not be saved, except by them.[21]

Lin’s visual sense, on good display in this passage, and his skewering of the serious politicians of the world would have put him in good company with Ye Qianyu and the other members of the Manhua Society. Like Wang Dunqing, he was fluent in both Chinese and English, having attended St. John’s for a time before going abroad to the US to study at Harvard. Like Huang Wennong, Ye Qianyu, Ji Xiaobo, Cai Shudan, and Zhang Meisun, meanwhile, Lin had worked for the Nationalist government following the Northern Expedition, but like most of the Manhua Society members he quickly became disillusioned with the KMT. Finally, much as the members of the Manhua Society eventually rejected the older term “satirical drawings” in favor of “manhua,” Lin Yutang famously promoted his own brand of comedy under the banner of youmo 幽默, a transliteration of the English word “humor.” [22]

In the early 1930s, Lin found himself a target of criticism from Lu Xun, who found fault with his flippant xiaopin wen 小品文 or “little prose pieces,” to use the translation used by the leading English-language of scholar of the form, Charles Laughlin.[23] Lu Xun disparaged Lin’s little prose pieces as “little decorations” 小擺設 or, to use Kirk Denton’s memorable translation, “bric-a-brac for the bourgeoisie.”[24] Described most simply by Laughlin as “an essay genre…that emerged in the 1920s and reached the peak of its popularity shortly before the War Against Japan broke out in 1937,” xiaopin wen developed in parallel with manhua, which as we have seen also emerged in the 1920s and, coincidentally enough, would peak in popularity in the mid-1930s. It is perhaps not surprising then, that manhua pioneer Feng Zikai was a prominent author of xiaopin wen, for which he favored the term suibi 隨筆, or ‘casual essay,’ mirroring his use of the term manhua, or ‘casual drawing.’[25]

Lin Yutang, primarily a writer, also dabbled in cartooning, for example publishing a humorous illustration of Lu Xun beating a drowning pug in the Peking Press Supplement 京報副刊 on January 23, 1926 (See Fig. 6.2).[26] This somewhat incongruous image was apparently in response to series of back and forth essays between Lin and Lu Xun criticizing the academic Chen Yuan 陳垣 (1880-1971) for supporting the closure of the Women’s College in Beijing. When Lin urged his friend to show restraint by saying, ‘one shouldn’t beat a drowning dog,’ 不打落水狗 Lu Xun jokingly responded that Chen Yuan was a ‘pug,’ 叭儿狗 which “…were so smug they behaved more like cats than dogs, [so] it was necessary to push them into the water and also give them a sound beating.”[27]

Figure 6.2 “Picture of Mr. Lu Xun Beating a [Drowning] Pug” 魯迅先生打叭兒狗圖 Lin Yutang, Peking Press Supplement 京報副刊, January 23, 1926.

One year later, Shao Xunmei launched a 10-day periodical, The Decameron 十日談, edited by Zhang Kebiao 章克標 (1900-2007), featuring political commentary by Shao Xunmei and others, with cartoons by Zhang Guangyu and other members of the original Manhua Society on the cover.[28] According to Shao Xunmei’s daughter, The Decameron was meant to supplant Modern, which was often delayed due to publishing problems and therefore unable to comment on current events in a timely fashion.[29]

In November, 1934, Shao Xunmei and Zhang Guangyu’s younger brother, Cao Hanmei, each contributed 2000 yuan to purchase China Arts Periodical Press and found a new publisher, with Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhengyu, and Ye Qianyu all receiving an equal share in the new partnership.[30] Using a similar name in English as his previous project, the goal of Modern Publications 時代圖書公司 are perhaps indicated their ambitions best through their Chinese name, which literally translates as “Modern Picture Book Company.”[31]

True to their name, Modern Publication would go on to publish a series of art books, including a reprint of Huang Wennong’s Collected Satirical Drawings and Things a Young Lady Must Know小姐須知, a 1932 collaboration between Shao Xunmei, who supplied the text, and Zhang Guangyu, who provided matching illustrations of beautiful young women. Apparently something of a joke, Things a Young Lady Must Know was made up of a series of short lines such as, “If you wear this flower, you must know that this flower is beloved by all.” 您如戴這朵鮮花時,要知這鮮花是人人所愛的 and “When you talk to your lover in the cold of winter, it’s best to sit close to the stove, to make yourself appear more coy.” 您與情人談話時,在冬令,宜近火爐,可以增嬌羞之美. In the forward, meanwhile, Shao added a note stipulating that the book was only to be sold to young, unmarried women, and that male customers buying the book should provide the name and address of a young lady on whose behalf they were claiming to buy the book. [32] Other books published by Modern Publications include a collection of Mr. Wang cartoons, and a series of travel drawings by Ye Qianyu, titled Ye’s Collected Quick Sketches 淺予速寫畫集.[33]

Much has been made of the fact that before partnering with the former members of the Manhua Society, Shao Xunmei was originally involved with the much more highbrow literary publication, the Crescent Moon Monthly 新月月刊 from 1928 to 1933. Originally founded with friend and fellow poet, Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1897-1931), regular contributors to the Crescent Moon Monthly included luminaries such as Hu Shi 胡適 (1891-1962), Liang Shiqiu 梁實秋 (1903-1987), and Shen Congwen 沈從文 (1902-1988), in addition to Lin Yutang. Jonathan Hutt argues that,

Rather than catering to a limited number of friends and colleagues, Shao’s was now aiming at the city’s increasingly sophisticated petty-bourgeoisie hungry for entertainment and enlightenment. Publications such as The Young Companion had proven that a huge market existed for this particular brand of lifestyle publication and Shao was keen to capitalise on their success. In severe financial distress, Shao had but one option left open to him; kowtow to the vulgar.[34]

Wang Jingfang, however, argues that Shao Xunmei had much more noble goals in mind, citing a short essay by Xunmei titled, “The Cultural Status of Illustrated Magazines” 畫報在文化界的地位, published in the October, 1934, issue of Modern. Xunmei defends his choice to publish illustrated magazines by making the case that highbrow periodicals have failed to capture the attention of the vast majority of Chinese, not because they do not understand them, but because they serve no practical purpose. Illustrated magazines, according to Xunmei, had the advantage of attracting illiterate readers who, having enjoyed the pictures, would be enticed to learn to read the text as well.[35]

Wang further argues that Xunmei influenced Modern and the other China Fine Arts Periodical Press publications to become more cultured, by including essays and interviews with famous figures such as Lin Yutang, discussed previously, public intellectual Hu Shi 胡適, painter Lu Xiaoman 陸小曼, educator Cai Yuanpei 蔡元培, and entrepreneur Wang Xiaolai 王曉籟. Additionally, aside from cartoonists, Shao convinced artists such Xu Beihong 徐悲鴻, Pan Xunqin 龐薰琴, An Ge’er 安格爾, Chang Yu 常玉 to contribute to his magazines.[36] Whether these efforts were merely a smokescreen for Xunmei’s more mercantile interests, or examples of a genuine attempt to raise the level of popular discourse is of course debatable, but it is nevertheless interesting to consider the possibility that there was an element of altruism behind the co-author of Things a Young Lady Must Know.

The Manhua Boom

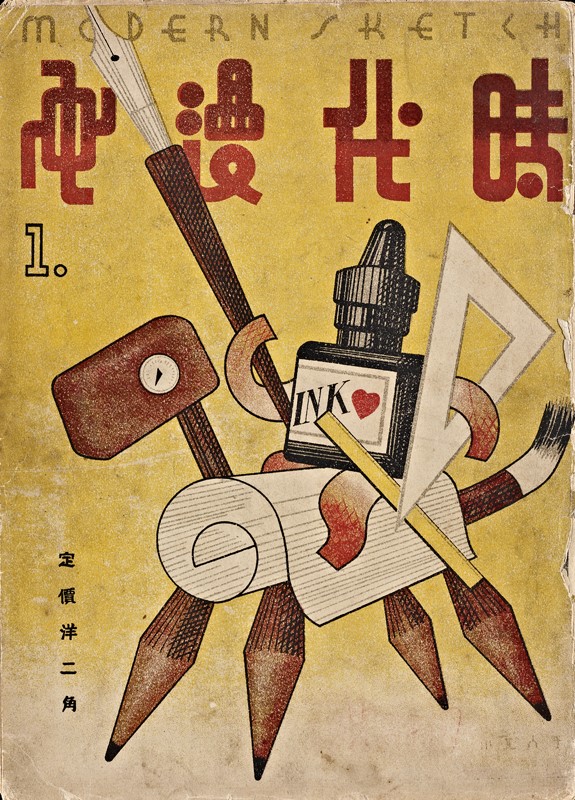

On January 24, 1934, a new monthly Modern Publications manhua magazine, Modern Sketch 時代漫畫 was launched with Lu Shaofei as the editor. Modern Sketch would prove to be one of the longer lived manhua periodicals, putting out 39 issues in the 42 months between its first issue on January 24, 1934 and its last on June 20, 1937, with each issue containing 32 pages of cartoons, photographs and essays, in addition to a full color front and back cover.[37]

Figure 6.3 Cover of the first issue of Modern Sketch by Zhang Guangyu, featuring the “Don Quixote of Manhua” 漫畫的堂吉訶德 by Zhang Guangyu, January 24, 1934

To explain the cover of the first issue of the first issue of the new periodical (see Fig. 6.2) Lu included a short note titled “Editor’s Filler” 編者補白:

On all sides a tense era surrounds us. As it is for the individual, so it is for our country and the world. Will things always be this way? I for one don’t know. But since the feeling won’t go away, one desires an answer, and the more one fails to find it, the more that desire grows. Our stance, our single responsibility, then, is to strive! As for the design on the cover of this first issue, it shall be our logo. Its meaning: Yield to None.

目下四圍環境緊張時代,個人如此,國家世界亦如此。永遠如此嗎?我就不知道。但感覺不停,因此甚麼都想解決,越不能解決越會想應有解決。所以,需要努力!就是我們的態度。責任也只有如此。這一期的封面的圖案,以後用做我們地表示,表明『威武不屈』的意思。[38]

Like Ye before him, Lu was also extremely productive, contributing a large number of his own cartoons and essays to his magazine. Modern Sketch was not without controversy however, running into a 3 month ban from the KMT government’s Central Office of Propaganda 中央宣傳部 February, 1936 for cartoons by Wang Dunqing which were said to “slander the government, damage international relations, and slander political leaders” 污蔑政府,、妨碍邦交、污辱领袖.[39] The same month saw additional bans on Zhang Guangyu’s Oriental Puck 獨立漫畫 (launched in September, 1935, following the appearance of the Zhang brother’s new publishing house, Shanghai Oriental Puck Press 上海獨立出版), and Huang Shiying’s Manhua and Life 漫畫和生活.[40]

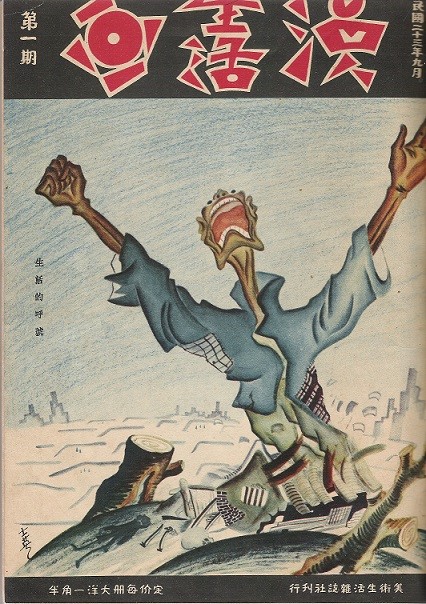

Manhua and Life was the latest iteration in a long string of manhua periodicals launched by Huang Shiying, beginning with the launch of the 32-page Manhua Life 漫畫生活on September 20, 1934.[41] Originally a spinoff of German-speaking social progressive Wu Langxi’s 吳朗西monthly art and literature journal Arts & Life 美術生活, Manhua Life was co-edited by Zhong Shanyin 鐘山隱,a Sichuanese landscape painter who also worked on Arts & Life, and the cartoonists Huang Ding 黃鼎, Zhang E張諤.[42] In addition to cartoons, thanks to Wu Langxi’s connections (much like how Zhang Guangyu was able to leverage Shao Xunmei’s social status for Modern), Huang Shiying was able to boost the prestige, and likely the sales, of Manhua Life by publishing essays from famous writers such as Lu Xun (who had been fiercely critical of both Shen Bochen and Lin Yutang), Mao Dun 茅盾 (1896-1981), and Lao She 老舍 (1899-1966).[43] Like Lu Shaofei and the cartoonists behind Modern Sketch, Huang Shiying and his staff had big ambitions for their little periodical, writing in the preface to their first issue:

Life is a big stage. We are all playing roles in a tragicomedy, and, at the same time, we are the audience for a tragicomedy. Even though the program changes every day, it never departs from the tragicomic mode. Let us open today’s program and take a look: the chaos of war, unemployment, famine, starvation, all occupy the grand stage of this tumultuous era. The lives of the masses in this era really are too cruel. And yet, in another corner of the stage, there exists a small minority who dance for joy at the mouth of the volcano. Such are the contradictions which exist in the world unfolding before our eyes. But we believe that this discord should disappear, and that sooner or later it will disappear.

世 界是一個大舞臺。人人是扮演悲喜劇的角色,人人又是悲喜劇的觀眾。舞臺上的節目雖然天天在變更,但總走不出悲喜劇的範圍。我們且翻開今天的節目來 看看:戰亂、失業、災荒、飢餓的大悲劇占據了這動亂時代的大舞臺。生長在這個時代的大眾的生活實在是太悲慘了。然而在舞臺的另一角卻有少數在這火山口上跳 舞享樂的人們。這樣展開在我們眼前的世界是充滿著何等的矛盾。不過我們相信這不調和的現象是應該消滅的,遲早是會消滅的。[44]

Fittingly, the cover of the first issue of Manhua Life, titled “The Cry of Life,” 生活的呼號 featured an emaciated Chinese man on his knees in the ruins of a demolished city, hands raised into the air, with a mouth open so wide that it obscures the rest of his face. For contemporary readers, ruined city would have immediately brought to mind the devastation wrought by the 1932 Japanese bombings in Zhabei. The pointed critiques in Manhua Life were not overlooked by KMT censors, however, who began removing content from the magazine as early as the second issue. To draw attention to the censorship, the editors choose to leave blank spaces where the three offending cartoons would have been printed. [45]

Figure 6.4 “The Cry of Life,” 生活的呼號 Manhua Life, Issue 1, September 20, 1934.

On June 21, 1934, Huang Wennong died of a ruptured stomach ulcer and the former Manhua Society members pooled together to pay for his funeral. Abandoned by his wife following the death of their child, Huang had drifted away from the cartooning world in the years prior to his death, with his last printed work being the Modern Publications reprint of his collected works.[46]

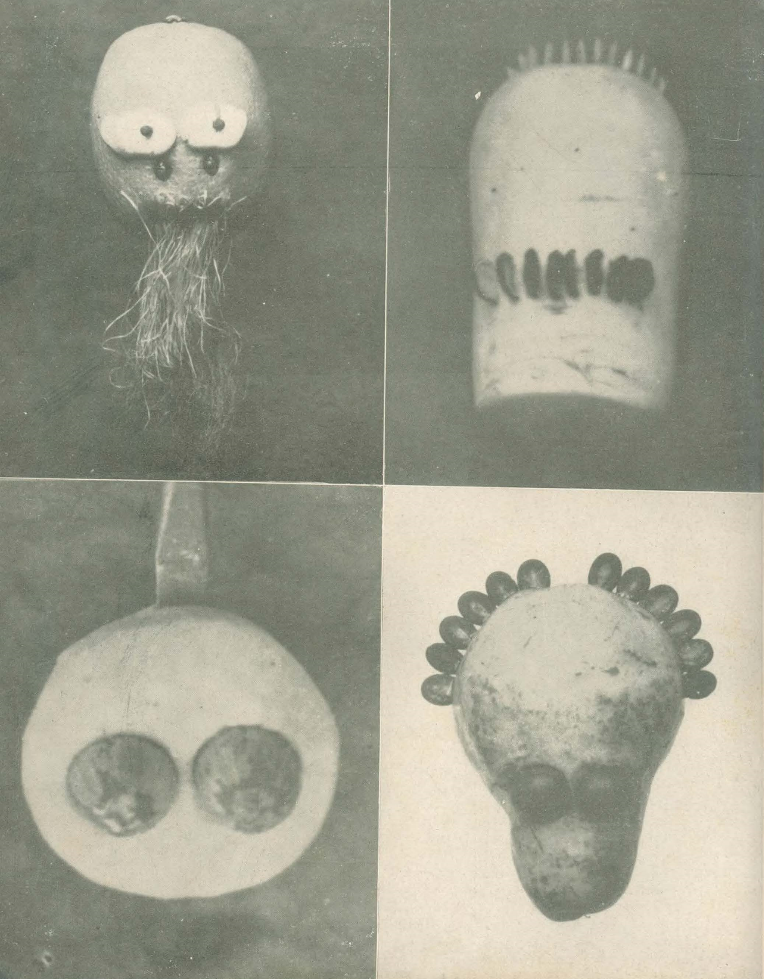

Huang’s spirit of satirical troublemaking was shown to alive and well, however, when a young cartoonist named Hu Kao 胡考(1912-1994) threw his hat into the ring five months later on November 15, 1934, with a new Modern Publications periodical titled The Spectator 旁觀者, which was banned after its first issue.[47] In addition to cartoons by Ye Qianyu and excerpts from founding Left League member Tian Han’s new musical, Storm on the Yangtze揚子江的暴風雨, likely of particular interest to censors was a two-page spread of famous faces creativity rendered in fruit and vegetables, titled “Heads of State” 元首 (See Fig. 6.5):

Art is always so mundane, and yet always so miraculous! What materials are these depictions of our god-like head of states made of? It turns that Wu Zhihui is made of: an apple, mung bean sprouts, and dried soybeans. Zhang Xueliang is: a pomelo, watermelon seeds, and soybean hulls. Chiang Kai-shek is: a turnip head, grains, and watermelon seed shells. Hu Hanmin is: a pear, Liangxiang chestnuts, and watermelon seeds. Lin Sen is: a lemon, fava beans, red beans, and a corn tassel. Sun Ke is: a skinned water chestnut, and lotus seed pods.

藝 術是永遠的平凡,也是永遠的奇跡!這些神似元首的造像又是甚麼材料? 原來吳稚暉的是:蘋果,綠豆芽,黃豆。 張學良的是: 文旦,西瓜子,毛豆莢。蔣介石的是:蘿卜頭,谷粒,西瓜子殼。 胡漢民的是: 洋梨,良鄉栗子,西瓜子。 林森的是: 檸檬, 豆板,赤豆,玉蜀黍的鬚。 孫科的是:去皮的荸薺,蓮子。[48]

Figure 6.5 “Heads of State” 元首, The Spectator, November 15, 1934.

In February, 1935, the monthly Masses Manhua 群众漫畫, co-edited by Cao Juren 曹聚仁 and Wang Minqi 江毓祺was launched.[49] In April of the same year, Cai Ruohong 蔡若虹and Zhuang Qidong 莊啟東took over editorship of Manhua Life, with Cai also launching his own periodical in the same month, Manhua Manhua 漫畫漫話.[50] Two more manhua periodicals were launched in April, 1935: Movies, Manhua 電影漫畫, co-edited by Gu Fengchang 顧逢昌and Zhu Jinlou 朱金樓 (1913-1992); and Manhua Phenomenon 現象漫畫 edited by Wan Laiming 萬籟鳴, Zhou Hanming 周漢明, and Xue Ping 薛萍.[51] In May, 1935, Zhu Jinlou launched Chinese Manhua 中國漫畫 and that very same month, Wan Laiming and Xueping’s Manhua Phenomenon folded after putting out just two issues, along with the Cao Junren and Wang Minqi’s only slightly longer lived Masses Manhua, which published 3 issues in total.[52] In July, 1935, Cai Ruohong’s Manhua Manhua folded, and Manhua Life folded two months later in September, 1935, having put out a total of 13 issues.

Meanwhile, on September 25, 1935, Zhang Guangyu launched Independent Manhua 獨立漫畫.[53] Two more manhua periodicals were launched in October, 1935: Popular Manhua 大眾漫畫, edited by Zhang Hongfei 長鴻飛, and 新世代漫畫 New Era Manhua, co-edited by Chen Liufeng 陳柳鳳 and Chen Mingxun 陳明勛.[54] Neither survived to put out a second issue. November saw one final periodical for 1935, 漫畫和生活 Manhua and Life, edited by Zhang E and Huang Shiying.[55]

Censorship and War

In February, 1936, both Lu Shaofei’s Modern Sketch and Zhang Guangyu’s Independent Manhua were ordered to cease publication by the KMT government’s Central Office of Propaganda. Zhang E and Huang Shiying’s Manhua and Life ceased publication the same month, likely for the same reason. In April, 1936, Modern Sketch was temporarily replaced with Manhua World 漫畫界, edited by Wang Dunqing, while Huang Shiying and Liu Yongfu launched Life Manhua 生活漫畫.[56] On May 7 of the same year, Zhang Guangyu re-launched Shanghai Sketch as Shanghai Puck (in Chinese, however, the name was unchanged) to replace Oriental Puck which had managed to run for 9 issues.[57] In June, Zhu Jinlou’s Chinese Manhua published its last issue, having put out a relatively impressive 14 issues. Huang Shiying and Liu Yongfu’s Life Manhua also put out its last issue in June 1936, having published 3 issues total. When Modern Sketch was re-launched by Lu Shaofei in June 20, 1936, Manhua World also continued to be published as a separate periodical. September 5, 1936 saw the launch of Huang Shiying’s Global Manhua 漫畫世界, which only lasted for a single issue, and on December 5, 1936 Wang Dunqing’s Manhua World published its last issue, for a total of 8 issues.[58]

Ironically, just as cartoons magazines were beginning to shut their doors, popular interest in the art form was hotter than ever, with the founding of the National Manhua Artist Association (NMAA) 中華全國漫畫作家協會 in the spring of 1937. Founded by former Manhua Society members Wang Dunqing, Ye Qianyu, Zhang Guangyu, and Lu Shaofei, the NMAA included a large of younger manhua artists such as Cai Ruohong, Huang Miaozi 黃苗子, Liao Bingxiong 廖冰兄, Lu Zhixiang 陸志庠, and Hua Junwu 華君武. In an announcement, they pledged to “unite the cartoonists of the nation, promote manhua art, and make Chinese manhua into a tool for social education” 團結全體漫畫家、共同推進漫畫藝術,使漫畫成為社會教育工具.[59] Eventually, branches of NMAA would be founded in Guangzhou, Xian, Wenzhou, and Hong Kong, among other cities.

In March, 1937, as one of the first activities sponsored by NMAA, Wang Dunqing launched Friends of Manhua 漫畫之友.[60] Not to be outdone, Zhang Guangyu and Ye Qianyu published an extra large format manhua periodical Puck 潑克, while Huang Yao 黃堯 (1917-1987) and Zhang Leping 張樂平 (1910-1992) launched Ox-head Manhua 牛頭漫畫 the same month.[61] Although both Puck and Ox-head Manhua only lasted for single issue, Friends of Manhua was slightly longer lived, lasting for 4 issues before folding in May, 1937, the same month that Modern Publication’s long running flagship periodical, Modern finally threw in the towel. Shortly thereafter Modern Sketch put out its final issue on June 20, 1937, while Zhang Guangyu’s Shanghai Puck, finished its run on June 30, 1937, with a total of 13 issues.[62]

On July 7 of the same year, a clash between Japanese and Chinese soldiers on the Marco Polo Bridge outside of Beijing quickly led to a series of escalating battles between KMT forces and the Kwantung Army. Having amassed some 90,000 troops in Northern China and occupied Manchuria, ostensibly to protect Japanese railways and commercial interests, the Kwantung Army (and even more so the over half-million-strong Imperial Japanese Army, and rapidly expanding navy, both with separate air divisions) represented a serious challenge to the mostly rag tag troops in the National Revolutionary Army.[63] With the exception of Chiang Kaishek’s German trained divisions, and graduates of the Whampoa Academy, who were mostly concentrated in the southern part of the country, the vast majority of the roughly 1.2 million troops that now made up the NRA were a mix of mercenaries and conscripts that had been brought into the military during the warlord conflicts of the early 1920s and the Northern Expedition of 1926-1928.[64]

Although China would not officially declare war on Japan until December 9, 1941, by the end of July, 1937, Chiang Kaishek and the Standing Committee of the KMT had voted in favor of launching an all-out “War of Resistance” against the Japanese forces in China.[65] Shanghai was a logical choice to open a second front in the conflict, given the large concentration of Chinese troops in the Chinese controlled parts of the city in light of the strategic importance of the city, but perhaps just as importantly, the presence of the foreign press. After a Japanese officer was killed in unclear circumstances at the hands of Chinese troops at Hongqiao airport to the west of the city, tensions began to escalate, with the NRA attacking Japanese positions in the city on August 13, 1937.[66] The following day, the poorly trained Nationalist air force accidentally bombed Nanjing Road in the international settlement, killing 1,740 civilians and injuring another 1,873.[67] Despite being greatly outnumbered, Japanese troops in Shanghai managed to hold out until IJA reinforcements began to arrive by sea in late August.[68]

In response to the Japanese invasion, on September 1, 1937, Wang Shuyang enlisted Zhang Guangyu, Zhang Zhenyu, and Ye Qianyu to became editors of the New Life Pictorial 新生畫報, soon changing the name to the Resist Japan Pictorial 抗日畫報.[69] Wang Dunqing, Ye Qianyu, and the young cartoonists Te Wei 特偉 (1915-2010) and Zhang Leping 張樂平 (1910-1992) meanwhile, mobilized the National Manhua Artist Association to form the National Salvation Cartoon Propaganda Corps 漫畫界救亡協會 (hereafter the Cartoon Corps) shortly thereafter, which launched its own propaganda periodical Save the Nation Manhua 救亡漫畫 on September 20. Pitched battles continued to be waged in and around Shanghai through September and October, with the NRA finally being forced to withdraw and cede the Chinese-controlled parts of the city center in late October.

During the three month long conflict, the Zhang brothers managed to publish 15 issues of the Resist Japan Pictorial, before leaving for the relative safety of Hong Kong. The Cartoon Corps, meanwhile, put out 11 issues of Save the Nation Manhua, with a core contingent joining the Second United Front of the KMT and CCP in Wuhan in January, 1938. As members of the Third Bureau of the Military Affairs Commission’s Political Affairs Department軍事委員會政治部第三廳under the leadership of Chinese Communist Party members Guo Moruo (also a founding member of the Left League) and Zhou Enlai 周恩來 (1898-1976), the Cartoon Corps launched a new bimonthly periodical, Resistance Manhua 抗戰漫畫, featuring denouncements of collaborators, exhortations to join the army, and graphic depictions of Japanese atrocities perpetrated on the bodies of Chinese women and children.[70] Ultimately publishing 12 issues between January and July, 1938, Resistance Manhua was forced to shut down due to shelling and encirclement campaigns by Japanese forces during the Battle of Wuhan. Lasting nearly four months from June to October, 1938, the Battle of Wuhan set the stage for the long, protracted conflict which was to last until Japan’s surrender following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by U.S. forces in 1945.[71] Like the second Battle of Shanghai the previous year, it also demonstrated the fragility of even the most robust of publishing industries, with much of the propaganda efforts during the remainder of the war being forced to resort to public exhibitions and murals in the absence of the necessary printing presses, and at times even ink and paper. [72]

Conclusion

[1] Chen, “China’s Militant Cartoonists,” 308.

[2] “Liang Da Kanwu zhi Fengxing” 兩大刋物之風行 [Two Popular Publications], Shenbao 申報, October 22, 1929, 16.

[3] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 70.

[4] “Yuezhe zhuyi ben kan zi xia qi qi yu Shidai Huabao hebing xiangqing qing yue di er ye!” 阅者注意 本刊自下起期起與時代畫報合併為半月刊 詳情請閱第二頁! [Note to Our Readers: Starting with Our next Issue, this Magazine Will Join with Modern Miscellany and Be Published Bi-Monthly. See Page Two for More Details!], Shanghai Manhua 上海漫畫, June 7, 1930, 8.

[5] Although he provides an overview of the transition from Shanghai Sketch to Modern Miscellany to Modern, Ye Qianyu is rather sketchy on the exact dates for when the various publications began and ended. Thankfully, in 2007 Wang Jingfang completed a dissertation on Shao Xunmei’s contributions to the publishing industry, providing more precise dates. See Wang Jingfang 王京芳, “Shao Xunmei he Ta de Chuban Shiye” 邵洵美和他的出版事業 [Shao Xunmei and His Publications] (Ph.D., East China Normal University 華東師範大學, 2007), 88.

[6] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 72–73.

[7] For an concise account of Shao Xunmei’s life and times, see Jonathan Hutt, “Monstre Sacré: The Decadent World of Sinmay Zau 邵洵美,” China Heritage Quarterly 22 (June 2010), http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?issue=022&searchterm=022_monstre.inc (accessed July 31, 2015). Throughout his essay Hutt refers to Modern as Epoch, a translation that does not seem to have been used by Zhang Zhengyu or the other publishers of the magazine. As John A. Crespi points out, “epoch” or “era” would be a much more literal translation of shidai in English. See “China’s Modern Sketch: The Golden Era of Cartooning 1934-1937,” MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2011, http://ocw.mit.edu/ans7870/21f/21f.027/modern_sketch/ms_essay01.html (accessed July 31, 2015).

[8] Wang Jingfang records that Xunmei’s name first appears on the list of editors for Modern Issue 1 (Vol. 2), published November, 1930. See “Shao Xunmei he Ta de Chuban Shiye,” 90.

[9] “Yinshua ji tuban zhi gailiang” 印刷及圖版之改良 [Improvement in Printing and Picture Plates], Shidai 時代, October 1930, Issue 12 (Vol. 1).

[10] “Bianwan yihou” 編完以後 [After Editing], Shidai 時代, August 1931, 26.

[11] See Wang Jingfang, “Shao Xunmei he Ta de Chuban Shiye,” 89, and Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 71.

[12] Zhang Guangyu 光宇 張, Jindai Gongyi Meishu 近代工藝美術 [Modern Commerical Art] (China Fine Arts Periodical Press 中國美術刋行社, 1932) cited in Crespi, “China’s Modern Sketch: The Golden Era of Cartooning 1934-1937.” For more on this important work, originally serialized in Modern, see Tang Wei 唐薇, “Zhang Guangyu Xiansheng yu Jindai Gongyi Meishu” 张光宇先生和《近代工艺美术》 [Mr. Zhang Guangyu and Modern Commercial Art], Zhuangshi 裝飾 (July 2, 2010), http://www.izhsh.com.cn/doc/9/689.html (accessed September 10, 2015).

[13] Mo Yajun, “‘Little Japan’ in Hongkou: The Japanese Community in Shanghai, 1895-1932” (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2004), 35–36.

[14] Christian Henriot, “A Neighbourhood under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars,” European Journal of East Asian Studies 9, no. 2 (December 1, 2010): 293.

[15] Chen, “China’s Militant Cartoonists.”

[16] Ibid.

[17] See “Memorandum on the Chinese Boycott of Japanese Goods,” Memorandum (Institute of Pacific Relations, American Council) 1, no. 4 (March 30, 1932): 1 and A Synopsis of the Boycott in China: The Chinese Government Encourages and Directs the Anti-Japanese Boycott. The Anti-Japanese Boycott by China is Tantamount to an Act of War. (The Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 1932).

[18] “Boycott, Bloodshed & Puppetry,” Time 18, no. 17 (October 26, 1931): 22.

[19] For a detailed account of the Shanghai Incident of 1932, see Frederic, Policing Shanghai, 1927-1937, 187–94.

[20] Henriot, “A Neighbourhood under Storm Zhabei and Shanghai Wars,” 310.

[21] Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living (Reynal & Hitchcock, 1937), 78.

[22] For a discussion of Lin Yutang and his concept of humor see Chapter 6 of see Christopher G. Rea’s The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015).

[23] For an analysis of the xiaopin form, see Laughlin’s monograph The Literature of Leisure and Chinese Modernity (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008).

[24] Kirk A. Denton, “Lu Xun Biography,” MCLC Resource Center, 2002, http://u.osu.edu/mclc/online-series/lu-xun/ (accessed October 5, 2015).

[25] Albeit at the suggestion of Zheng Zhengduo. See Barmé, An Artistic Exile, 89.

[26] Chen Zishan 陳子善, “Lin Yutang de Manhua” 林語堂的漫畫 [Lin Yutang’s Cartoons], Wenhuibao 文彙報, August 1, 2015, http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:7rNh0hwaOzgJ:whb.news365.com.cn/bh/201508/t20150801_2109885.html+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us (accessed October 3, 2015); “Lu Xun Xiansheng Da Baergou Tu” 魯迅先生打叭兒狗圖 [Picture of Mr. Lu Xun Beating a Pug], Peking Press Supplement 京報副刊, January 23, 1926.

[27] Paraphrased by Gloria Davies in Lu Xun’s Revolution (Harvard University Press, 2013), 225.

[28] Wang Jingfang records that the editor of Decameron was Yang Tiannan 楊天南. See “Shao Xunmei he Ta de Chuban Shiye,” 126

[29] Xiao Hong 綃紅, “Cong Shi Ri Tan Kai Tianchuang Shuoqi” 從《十日談》開天窗說起 [On the Skylight Opened by The Decameron], Bolan Qunshu 博覽群書 (February 7, 2011), http://epaper.gmw.cn/blqs/html/2011-02/07/nw.D110000blqs_20110207_4-04.htm?div=-1 (accessed October 3, 2015).

[30] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 70.

[31] Again, the most literal translation of shidai is actually “epoch.” For the context in which it is used here as the name of a series of companies and magazines with a different, and consistent official English translation for the word, however, “modern” is a more logical translation.

[32] Yao Sufeng 姚蘇鳳 (1906-1974) is said to have written a parody of this book titled Things a Young Lad Must Know, which contains the line, “When you talk to a young lady, whatever you do, don’t let your Wuxi or Changzhou accent slip out.” 與小姐們交際時,千萬不可露無錫及常州宜興等處的土音. Zhang Guangyu was, of course, originally from Wuxi, and Shao Xunmei’s family originally hailed from Changzhou, See“Xiaojie Xu Zhi yu Xiaoye Xu Zhi” 《小姐須知》與《少爺須知》 [Things a Young Lady Must Know and Things a Young Lad Must Know], Shafengjing Ji de Boke 煞風景集的博客, August 22, 2011, http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_5e8246090100tr3h.html (accessed October 2, 2015).

[33] Ye Qianyu also recalls that Zhang Guangyu’s groundbreaking 1935 collection Folk Love Songs民間情歌 was published by the Modern Press. Although originally serialized in Modern, the collection seems to have been published by the Zhang brother’s Independent Press in 1935. See Tang Wei 唐薇, “Minjian Qingge Hua Ji Tan Yuan” 《民間情歌》畫集探源 [Exploring the Sources of Folk Love Songs], Baiyaxuan 百雅軒, n.d., http://baiyaxuan.com/longhair/show/tack-46-544.html (accessed October 2, 2015) and Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 72.

[34] Hutt, “Monstre Sacré: The Decadent World of Sinmay Zau 邵洵美.”

[35] Wang Jingfang, “Shao Xunmei he Ta de Chuban Shiye,” 99–100

[36] Ibid., 106.

[37] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Shidai Manhua (Shanghai)” 时代漫画 (上海) [Modern Sketch (Shanghai)], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 599–600.

[38] Lu Shaofei 魯少飛, “Bianzhe Bubai” 編者補白 [Editor’s Filler], Shidai Manhua 時代漫畫, January 1934, 38 translated by John A. Crespi in “China’s Modern Sketch: The Golden Era of Cartooning 1934-1937.”

[39] Ding Xi, “Shidai Manhua (Shanghai).”

[40] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Duli Manhua” 獨立漫畫 [Independant Manhua], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 603; Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua he Shenghuo” 漫畫和生活 [Manhua and Life], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 603–4.

[41] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua Shenghuo” 漫畫生活 [Manhua Life], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 600–601.

[42] Arts & Life was published from April 1, 1934 to August 1937, total of 41 issues, and originally published by either Three-One Press 三一印刷公司 or Three Person Press三人印刷公司. One of founders of this company, Jin Youcheng金有成, appears to have been the owner of a rubber shoe factory. I have not been able to find the profession of the other, Yu Xiangxian俞象賢. Most sources record that Manhua Life was printed and distributed by美术生活杂志社, so it seems likely that at some point this company took over from the original publisher. See

[43] Interestingly, Zheng Zhenduo, the original publisher of Feng Zikai, who is thought to have coined the term ‘manhua’ was also a contributor to the magazine.

[44] Shiying Huang 黄士英, “Kaichangbai” 開場白 [Prologue], Manhua Shenghuo 漫畫生活, September 20, 1934.

[45] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua Shenghuo” 漫畫生活 [Manhua Life], Meishu cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷 (Shanxi Renmin Meishu Chuban She 陝西人民美術出版社, November 2000), 600–601.

[46] Ye Qianyu, Ye Qianyu zizhuan: Xixu cangsang ji liunian, 97.

[47] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Pangguanzhe” 旁觀者 [The Spectator], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 601–2.

[48] “Yuanshou” 元首 [Heads of State], 旁觀者, November 15, 1935.

[49] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Qunzhong Manhua” 群众漫畫 [Masses Manhua], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 602.

[50] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua Manhua” 漫畫漫話 [Manhua Manhua], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 602.

[51] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Dianying Manhua” 電影漫畫 [Movies, Manhua], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 602; Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Xianxiang Manhua” 現象漫畫 [Manhua Phenomenon], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 602.

[52] Yihai Jiang 蔣義海, ed., “Zhongguo Manhua” 中國漫畫 [Chinese Manhua], Manhua Zhishi Cidian 漫畫知識辭典 (Nanjing Daxue Chubanshe 南京大學出版社, 1989), 68–69.

[53] Ding Xi, “Duli Manhua.”

[54] While New Era Manhua is listed on the Chinese Manhua Database 中國漫畫專題庫 website sponsored by the National Digital Culture Network 全國文化信息資源共享工程it does not appear to have made it any of the major Chinese art or publishing encyclopedias. See “[Zhongguo Manhua Zhuanti Ku] – Quanguo Wenhua Xinxi Ziyuan Gongxiang Gongcheng” [中國漫畫專題庫]-全國文化信息資源共享工程 [[Chinese Manhua Database] – National Digital Culture Network], n.d., http://www.bjgxgc.cn/manhua/ (accessed October 2, 2015).

[55] Ding Xi, “Manhua Shenghuo.”

[56] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Shenghuo Manhua” 生活漫畫 [Life Manhua], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 604.

[57] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Shanghai Manhua (Shanghai Banyuekan)” 上海漫畫(上海半月刊) [Shanghai Sketch (Shanghai Bimonthly)], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 604.

[58] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Manhua Shijie (Shanghai)” 漫畫世界(上海) [Global Manhua (Shanghai)], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 604.

[59] Zhang Shaosi 章紹嗣, “Zhonghua Quanguo Manhua Zuojia Xiehui” 中華全國漫畫作家協會 [National Manhua Artist Association], 中國現代社團辭典 (Wuhan: Hubei People’s Press 湖北人民出版社, 1994), 180–81, Wuhan.

[60] Wei Qiao 魏橋 and Zhejiang Provincial Historical Figure Commitee 浙江省人物志編纂委員會, eds., “Wang Dunqing” 王敦慶 [Wang Dunqing], Zhejiang Historical Figures 浙江省人物志 (Hangzhou: 浙江人民出版社, 2005), 370–71, Hangzhou.

[61] Ding Xi 丁西, ed., “Poke” 潑克 [Puck], Meishu Cilin 美術辭林, Manhua Yishu Juan 漫畫藝術卷, November 2000, 604; “1937 Nian 5 Yue 1 Ri: Niutou Manhua” 1937年5月1日:《牛頭漫畫》 [May 1, 1937: Ox-Head Manhua], Huang Yao Foundation, n.d., http://www.huangyao.org/519.html (accessed October 3, 2015).

[62] Ding Xi, “Shanghai Manhua (Shanghai Banyuekan).”

[63] Hans J. Van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China 1925-1945, Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia (Routledge, 2003), 193.

[64] This number is a rough estimate based on a telegram sent by Chiang Kai-shek in November, 1941. See Ibid., 273–74.

[65] The reason that China did not declare war on Japan in 1937 appears to have been to avoid running afoul of the Neutrality Acts of 1935, 1936, 1937, and 1939 which prevented the U.S. government from providing military or financial aid to belligerents, with the goal of preventing the U.S. from becoming involved in World War II. See “Neutrality Acts,” The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the U.S. Military (Oxford University Press, 2002), http://www.oxfordreference.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/view/10.1093/acref/9780199891580.001.0001/acref-9780199891580-e-5519 (accessed October 5, 2015) and Van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China 1925-1945, 196.

[66] “CLASH OF ARMIES. Nanking Force in Action NEAR PEIPING. Heavy Shelling. LONDON, Aug. 11.,” The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW, August 12, 1937), 9

[67] Paul French, “Black Saturday – August 14, 1937,” China Rhyming, n.d., http://www.chinarhyming.com/2015/08/14/black-saturday-august-14-1937/ (accessed October 5, 2015); Carl Crow, Foreign Devils in the Flowery Kingdom (Earnshaw Books, 2007), 283–86.

[68] For a detailed account of the Battle of Shanghai, see Van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China 1925-1945, 211–16.

[69] Wei Qiao 魏橋 and Zhejiang Provincial Historical Figure Committee 浙江省人物志編纂委員會, eds., “Wang Shuyang” 王叔旸 [Wang Shuyang], Zhejiang Historical Figures 浙江省人物志 (Hangzhou: 浙江人民出版社, 2005), 370–71, Hangzhou.

[70] For an analysis of role depictions of rape and mutilated bodies played in Resistance Manhua and other wartime cartoon propaganda see Louise Edwards, “Drawing Sexual Violence in Wartime China: Anti-Japanese Propaganda Cartoons,” The Journal of Asian Studies 72, no. 3 (August 2013): 563–86.

[71] Van de Ven, War and Nationalism in China 1925-1945, 226–27.

[72] For first-hand accounts of cartooning during the war, see John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Cartooning and Wartime China: Part One — 1931-1945,” International Journal of Comic Art 10, no. 1 (April 15, 2008): 76–139. Good examples of the relatively poor quality of wartime printing can also be seen in Huang Yao’s collections from this time period, such as Houfang de Chongqing Er 後方的重慶二 [At the Backlines of Chongqing, Part II] (Iron Press 鐵社, 1938), available online at “August 1938: At the Backlines of Chongqing 2,” Huang Yao Foundation, n.d., http://www.huangyao.org/578.html (accessed October 5, 2015) and Chongqing Manhhua 重慶漫畫 [Chungking in Cartoons] (Guilin: Science Book Press 科學書店, 1943), available at “June 1943 Chongqing Cartoons,” Huang Yao Foundation, n.d., http://www.huangyao.org/776.html (accessed October 5, 2015).