Inspired by the tragedy of missing Eileen Chow’s presentation on Monkey King cartoons, here is the full text of my talk on pop culture adaptations of Journey to the West for everyone who wasn’t able to make it to our panel at AAS 2016 in Seattle this past weekend, The Construction of Xiyouji in the Sinographic Cosmopolis and Beyond. Some of these will already be familiar to readers of this blog, but others will (hopefully) be new:

Cut off my head and I’ll still go on talking,

Lop off my arms and I’ll sock you another.

Chop off my legs and I’ll carry on walking,

Carve up my guts and I’ll put them together.

[…] To bath in hot oil is really quite nice,

A warm tub that makes all the dirt gone.

–Journey to the West, Chapter 46 (translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Foreign Language Press)

So speaks Sun Wukong, better known in English as the Monkey King, after Monkey, British sinophile Arthur Waley’s enduring early 20th century translation of Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West 西游记. Thanks to Waley’s judicious to abridgement of the massive Ming dynasty novel into a much shorter and (arguably) more readable novel, for a time at least The Great Sage was able to enjoy an equal measure of fame both at home and abroad. Although the novel is less well known today, nearly a century later, Monkey has many ways found an even greater success—as a cartoon character.

1st Edition Hardcover of Arthur Waley’s translation of Monkey (George Allen & Unwin, 1942) designed by Duncan Grant [back]

To my knowledge, no systematic study of Monkey King comics, cartoons, animations, plays, live action TV dramas, movies, etc. has ever been attempted. Perhaps the task is too daunting, or perhaps it seems redundant, given the very ubiquity of Monkey King merchandise and media already flooding the Chinese marketplace–especially in year of monk-orological significance, Anno Simian. At times I even suspect that stronger emotions may be at play: as one friend (Chinese American, but also an American living in China) put it when I mentioned that I was writing a paper on the topic, “Oh god, which of the eight million versions are you going to do?”

Store fronts in Sanlitun, Beijing March 2016

For those unfamiliar with Chinese society, the Monkey King is usually something of a happy discovery–a quirky cousin to Hanuman of the subcontinent, or a Chinese trickster figure akin to Northern Europe’s Loki or Coyote of the American Southwest. At heart, Monkey is a myth, with all that the word entails (pun intended). If he seems little two-dimensional at times, can we really blame him? Born into simpler times and common to every culture and every continent, mythic figures were intended to play specific roles in narrowly defined morality plays. Whether hero, god, trickster, or fair maiden, one could hardly expect a character to go against type, any more than a fish might shed its scales, or a bird give up its wings. Ontologically speaking, beyond one’s actions, there wasn’t whole lot ‘there’ there.

So, based on what he does (and does not), who is Monkey? In the books at least, first and foremost, Monkey is loyal to his master, the foolish and defenseless monk Tripitaka. (I was recently cast in the role of Tripitaka for a Chinese New Year event at my university on the basis of my ability to effect a vacant stare and act magnanimous–or to put it the way my advisor did, “The perfect idiot!”) This is most obviously where a great many adaptations of Journey to the West go off the rails, because by and large Tripitaka has not survived the transition to the screen, silver or otherwise, nearly as well as his hairy disciple.

Perhaps it goes without saying that a celibate monk whose primary role in the novel is to avoid being eaten by monsters or raped by succubae (all the while dispensing the wisdom of the dharma) hardly seems like the makings of a good kids’ movie. Or perhaps he simply hasn’t found the right vehicle for his shiny pate— for example, the ‘beautiful man’ 美男子of Chinese web series Unthinkable 万万没想到 shows promise, but quickly falls into crude homophobia.

“I think I’d still rather go my own way and just be a ‘beautiful man.’” – Tripitaka in a 2014 sketch from Unthinkable

Pigsy on the other hand, has fared much better, with his obvious physical attributes (he’s a fat dude with a pig’s head), and relatable goals in life (women, wine, and gluttony, in that order). In fact, in one of my favorite adaptations, Zhang Guangyu’s Manhua Journey to the West, it could almost be said that Monkey plays a supporting role to his corpulent companion, who the likewise corpulent Zhang Guangyu may have seen something of himself and his friends in. In other works, such as Italian cartooning duo Silvero Pisu and Milo Manara’s Ape (serialized in the venerable pages of Heavy Metal magazine in 1983), Monkey and Pigsy seem to have been conflated into a single character, creating a sort of horny, hungry, hairy superman who whiles away his days in the Jade Palace, attended on by a bevy of immortal maid servants.

And of course, we would be remiss to overlook Sun Wukong’s most famous (and yet least obvious) incarnation, the Japanese man-child, Sun Goku. Not content to recreate a single Monkey, mangaka Akira Toryiama populated his alien world (made up of islands that look strikingly similar to the Japanese archipelago) with entire race of Money Kings: the super saiyens, a race of half-men, half-monkeys, who, truth be told, have little in common with the Great Sage. To be charitable, Goku rides around on a cloud, fights with a staff, and is adept at kung fu. He also has a friend who is a monk, and his grandfather might as well be channeling Zhu Bajie, for all the mischief he gets up to. But even in broad strokes, the world of Dragon Ball is cut from a whole new cloth and Journey to the West provides only the most rudimentary of influences.

Master Roshi = Zhu Bajie?

This popular work might be contrasted with a more recent (and much more faithful) addition to the Monkey King canon, Gene Luen Yang’s 2006 graphic novel American Born Chinese, in which Yang skillfully uses the legend of the Monkey King to explore his own childhood experience of growing up Chinese American. Yang’s Monkey King is a brash and bold symbol of Chinese cultural vitality, forming a stark comparison to the buck-toothed living stereotype of an exchange student who comes to visit from China.

Now, it is arguable that there really are two Monkeys: the Monkey of the first ten or so chapters, before he is tamed with a golden headband, and the Monkey of the remaining ninety. Clearly it is the former Monkey who has found a ready audience of wide-eyed children—and equally wide-eyed film producers and book editors on the hunt for domestic IP that can (finally) compete with Western superheroes.

Perhaps just as much a superhero, though, Monkey is the perfect cartoon character—indestructible, indefatigable, wisecracking. He’s like a Ming dynasty Looney Toon, Bugs Bunny ala the Pali scriptures:

“Since hearing the Way,” Sun Wukong said, “I have mastered the seventy−two earthly transformations. My somersault cloud has outstanding magical powers. I know how to conceal myself and vanish. I can make spells and end them. I can reach the sky and find my way into the earth. I can travel under the sun or moon without leaving a shadow or go through metal or stone freely. I can’t be drowned by water or burned by fire. There’s nowhere I cannot go.”

– Journey to the West, Chapter 3 (translated by W.J.F. Jenner, Foreign Language Press)

The idea to cast Monkey in export-oriented kiddy fare isn’t something recent, by the way. The first Chinese animated film from way back in the 1940s, Princess Iron Fan, is said to have been produced after the Wan brothers saw Walt Disney’s Snow White in a Shanghai movie theatre, and (it really must be said) their Monkey bears a striking resemblance to a certain white-gloved mouse. Released in Japanese-occupied Shanghai in 1941, it went on to great fame in Japan, eventually inspiring a young Osama Tezuka. The Wan brothers most famous film, meanwhile, Havoc in Heaven, was produced to compete on the international film circuit—primarily fellow traveler nations outside of the Soviet Union, but eventually further afield as well.

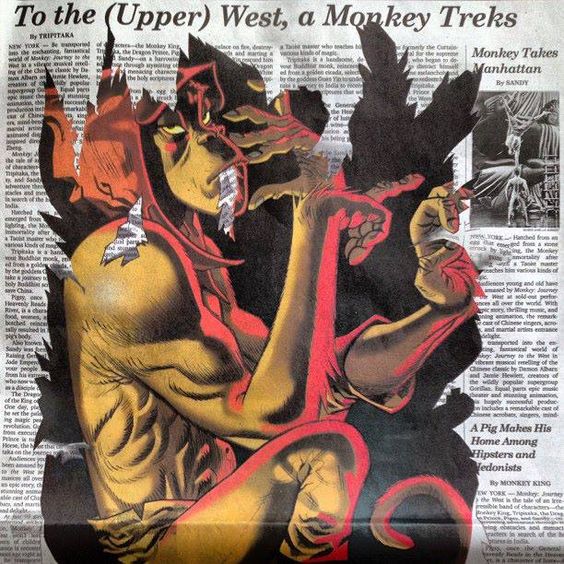

Waley’s abridgement aside, Monkey has yet to achieve real success in the English-language world. Perhaps the next closest he has come is through the work of Jamie Hewlett, a comic book artist who partnered with fellow Brit, the musician Damon Albarn to form the cartoon super group Gorillaz, made up of cartoon simians. While the connection to the Great Sage may not seem obvious, Hewlett went on to work as the art director for Chen Shi-Zheng’s 陳士爭 2007 stage production of Monkey: Journey to the West which managed an impressive five year run. This project later earned Hewlett a job in 2008 animating a preview for the 2012 London Olympics titled, of course, Monkey.

Monkey eats up his good press in a drawing by Jamie Hewlett (n.d.)

If Monkey seems to have found a special place in the hearts of the people of the UK, then it might owe something to 1978 Japanese TV series of the same name, broadcast only one year later in an embarrassingly Orientalized dub on the BBC. (There’s even an obscure shoegaze band from the mid-2000s, Monkey Swallows the Universe, which took their name from the series.) Japan of course, has its own Monkey tradition, which includes not only Dragonball and the disco drama, but also Katsuya Terada’s寺田克也 dark graphic novel from 1998, The Monkey King西遊奇伝 大猿王.

Perhaps inspired by Terada, in 2002 Hong Kong manhua master James Khoo Fuk-lung 邱福龍 debuted a muscled shape-changing Monkey on the pages of the The Sage King 大 聖王, a superhero adaption par excellence, complete with fireballs and lighting bolts. And of course, there various live-action film versions of Monkey which have appeared in mainland CG extravaganzas over the last decade, which martial arts legends such as Jet Li and Donnie Yen (with no lack of prosthetic assistance) filling the titular role.

The most well-remembered Monkey in the mainland, however, is Liu Xiao Lingtong 六小龄童, of the legendary 1980s TV series which, some thirty years later, still forms a core staple of mainland broadcasters rerun loops, having been played an estimated 2000 times. Filmed between 1982 and 1987, the first series covers some 74 chapters of the novel in 25 episodes, with the show being revived from 1998 to 1999 to depict a further 25 chapters of material in 16 episodes. Liu Xiao Lingtong made a surprise comeback earlier this year when a controversy erupted over his absence at the CCTV Spring Gala Festival. Not one to miss an opportunity to cash in on untapped nostalgia, Pepsi quickly filmed an ad just as syrupy sweet as their unadulterated product which just as quickly went viral on the Chinese internet and earned Mr. Lingtong a place on an another station’s spring gala show.

Liu Xiao Ling Tong’s deliciously viral Pepsi ad

To get down to brass tacks though, what exactly is it about Monkey that tickles the Chinese funny bone so? Is it his mischievousness? His all-powerfulness? His loyalty to his master? I would argue that it is something deeper in the DNA of the character, a combination of affect and delivery that comes through even in the original text. Monkey ranks among those rare fictional characters who have outlived the relevance of their origins—in China, he stands alongside figures such as Guan Yu, Wu Song, and Jia Baoyu. For Western audiences, he might be compared to cultural icons such as Santa Claus or the Easter Bunny. He really is that big and that important.

In the strict order of Chinese society, Monkey appeals arguably because he is a transgressive character. Only Monkey could get away with thumbing his nose at the high and mighty—a rare quality in Chinese heroes who tend more often to be racked with questions of propriety and loyalty. For Monkey, loyalty is never a question because it exists in his heart as obvious as the gold band on his head. Monkey is fearless, sexless, and (post gold band) desireless. He’s pure superego, the id and ego conquered. And unlike the melodramatic characters of Three Kingdoms, or the didactic satire of Jinpingmei, there’s very little hand-wringing over the state of the nation on the part of Monkey or his fellows.

The four jolly pilgrims on a 1979 PRC stamp issued to commemorate Journey to the West

Journey to the West, after all, is the ultimate a road trip. Four friends, four weeks (or is it four years? Or perhaps four decades?), and four thousand miles. He’s a cartoon, but he’s also more than a cartoon—there is an undeniable living, breathing vitality in the character of Monkey. It’s fun to speculate on what the future holds in store for adaptations of the Great Sage: Journey to the West in Space 星际西游记! Or maybe Sun Wukong and the Tomb Robbers 盗墓者与孙悟空? When nothing else in the world seems certain, the one thing I’m willing to bet on is bigger and better versions of Monkey—and maybe even a modicum of fame in the English-speaking world, too.

![Monkey, 1st edition cover [front]](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/image001.jpg)

![Monkey, 1st edition cover [back]](http://www.nickstember.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/image003.jpg)