In my experience learning Chinese over the past decade, one of the biggest challenges I’ve faced is getting enough practice reading (and writing) characters:

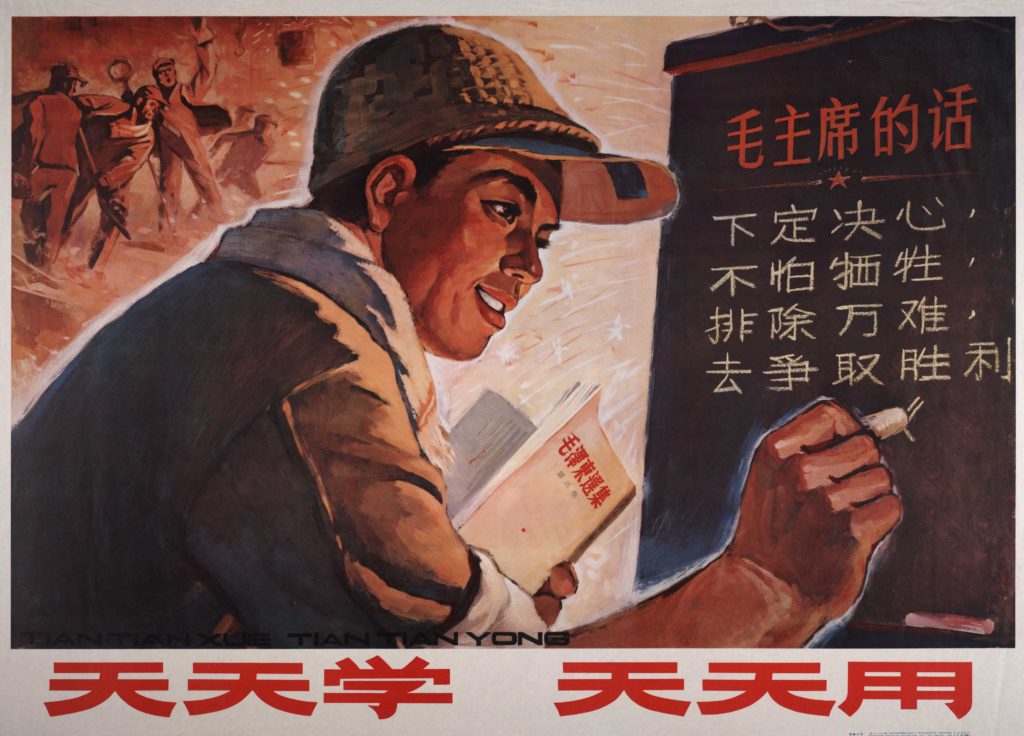

“Study them every day, use them every day” 天天学,天天用 1

Characters take an inordinate amount of time to memorize, and the lack of spaces between words means that proper nouns, set phrases, and foreign transliterations have to be parsed out from the more common vocabulary of everyday writing.

This is the easy answer for why so few Anglophones read untranslated Chinese literature:

Because Chinese is hard.

As the old joke goes, though:

Q: What’s the difference between ignorance and apathy?

A: I don’t know and I don’t care!

My suspicion is that there are a lot of people out there like me — people who are being held back not so much by the difficulty of learning Chinese, as by the difficulty of finding things to read in Chinese, so that we can actually get the practice we need to become (and stay) functionally literate.

Ignorance and apathy are self-perpetuating, of course: The less one reads in Chinese, the harder it is to pick up a book or story to read casually.2

At the same time, one hears over and over again that nothing worth reading is being published in China today. Just a couple of days ago, Ha Jin, an author who I respect and admire, was quoted on LitHub saying that, “Many of my novels—A Free Life, War Trash, A Map of Betrayal—which have political resonance, are not allowed to published.”3 Can Xue has gone even further, saying, when asked about contemporary Chinese literature, “I have no hope, and I don’t feel like evaluating it.”4

Setting aside, for the moment, questions of censorship and literary merit (which seem to, somewhat conveniently, to do double duty as pitches for dissident lit), genre fiction—particularly short fiction—provides interesting examples of ‘marginal’ or ‘weird’ literature: the queer, the dystopian, the creepy.

The trick is finding it.

For a long time, the twin pillars of Chinese science fiction were Science Fiction World 科幻世界, which was founded in 1979, and New Science Fiction 新科幻, founded in 1994. NSF went out of print at the end of 2014, but you can still read back issues from the last two years of their run, which are available for purchase here.

Since late 2012 SFW, meanwhile, has generously provided a public WeChat account (‘scifiworld’) with re-posted stories and articles. If you don’t have the app, or don’t want to read things on your phone, you can use this mirror. It’s pretty bare bones, but it gets the job done:

Chuansong.me, better than nothing

If you’re ready to take the leap to buying full issues of SFW (albeit from a couple of months back), you can find those here or here. Both sites accept payments through your WeChat wallet, which you can load with money off a credit card.

Moving into the strictly online publications, there are several options:

SF Comet 彗星科幻, an online bilingual sci-fi contest launched by Li Zhaoxin 李兆欣in 2014.5 Although it’s been on hiatus since late last year, the archives are all still up. There is also a pile of unpublished material that should be seeing the light of day soon. Here’s a story by Zhang Ran 张冉 about a brain operation gone wrong.

Douban Reading 豆瓣阅读, featuring self-published novellas and short stories (somewhat like Kindle Direct). Sci-fi is here, while fantasy is over here. Lots of interesting choices here, like this one about a planet of Morlocks and Eloi, or this (topical) one about an election.6 (They also sell ebooks, but these tend to be translations out of English, since relatively few Chinese sci-fi and fantasy authors write novels.)

Kedo 蝌蚪五线谱, online sci-fi publication which is partially government-funded. Seems to be very active at the moment.

Science Fiction Digest 科幻文汇, an online forum and digital magazine that appears to be somewhat defunct at the moment, but has extensive archives available for free.

Micro SF, an iOS app sadly not available through the US version of the Apple store.

Aside from these, here are two more projects worth checking out, which lean more towards fantasy and slipstream:

ONE·一个 , one picture, one story / essay, and the answer to one question, posted daily. Launched by Han Han 韩寒, and co-edited by Ma Yimu 马一木, ONE also posts on WeChat (‘one_app’) three days earlier than the website. Just last week they published a story about mermaids dealing with climate change.

ZUI Found 文艺风尚, edited by the author Di An 笛安, and founded by Han Han’s arch rival (of sorts), Guo Jingming 郭敬明. They do have a WeChat account (‘wenyifengshang’) which they sometimes post short fiction to, like this riff on Kafka’s Metamorphosis by Mi Yuwen 米玉雯. Full issues of the magazine are available to download on Amazon.cn, but if you’re not based in China you’re pretty much out of luck.

This is just a start, obviously. As a translator trying to break into agenting, I know from experience that the biggest challenges acquisitions editors face are 1) finding out what’s out there and 2) pitching projects to their bosses. I really do hope that we’ll get to the point where sites like LitHub can do more than bemoan the Chinese literature that isn’t, and celebrate the Chinese literature that is.

- ‘Them’ here isn’t actually characters, it’s ‘the words of the Chairman Mao’ but same diff, right? [↩]

- In language acquisition studies, this is referred to as ‘attrition’ and it probably affects us more than we think, since most of us have a pretty high tolerance for reading words that we don’t entirely understand. It’s more obvious when it comes to spelling (or writing characters), especially when we’re deprived of spell check (and IMEs). Two related concepts are the ‘plateau effect,’ which points to the fact that we learn L2 languages in stages, rather than all at once, and ‘fossilization,’ which refers to becoming trapped at a sub-fluent level. [↩]

- Ha Jin on the Long Reach of the Chinese Government: Love, Betrayal, and the Totalitarian Machine [↩]

- Q&A with Author Can Xue on the State of Chinese Literature [↩]

- Hat tip to Ken Liu. [↩]

- Kudos to Shaoyan Hu for suggesting Douban, Kedo and SFD. [↩]