Chinese comics, or manhua 漫畫, as they are known in Chinese, are hard to pin down, in large part because the term ‘manhua’ is used in so many different and often contradictory contexts.

Context 1. Manhua which are exclusive to China

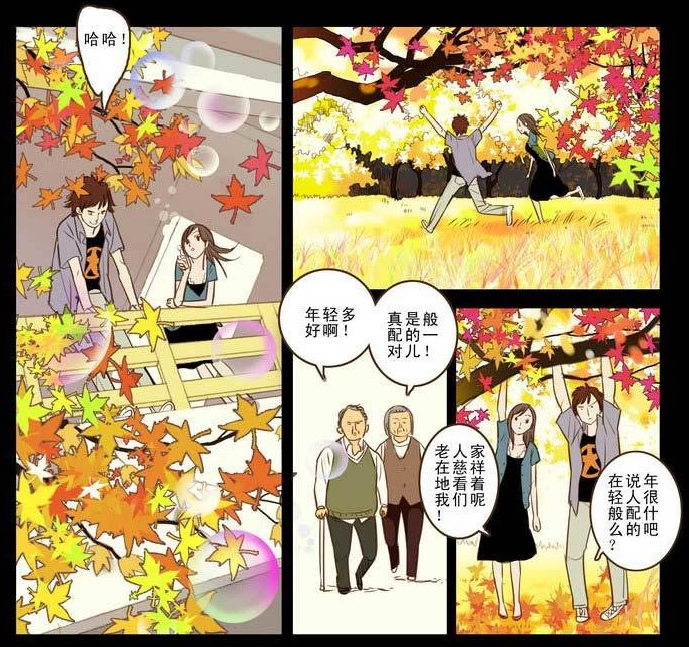

“Take Love to the Limit” by Yao Feila // 《將愛情進行到底》 姚非拉

Generally whenever the term is used in English, it refers to Sinophone1 comics, or what are generally called guochan manhua 國產漫畫, or ‘domestic comics’2 within the PRC.3 In English the term ‘manhua’ is often used highlight the differences between Chinese comics and Japanese manga, similar to the way in which the term ‘manhwa’ is used to describe Korean comics. All the same, these comics tend to be very similar in appearance to Japanese comics. One notable exception are wuxia 武俠 (martial chivalry) comics from Hong Kong which were developed by Tony Wong Yuk-long 黃玉郎 during kung fu craze the 1970s, which seem to have more in common with hyper-muscular American superhero comics.

Context 2. Manhua as inclusive global medium

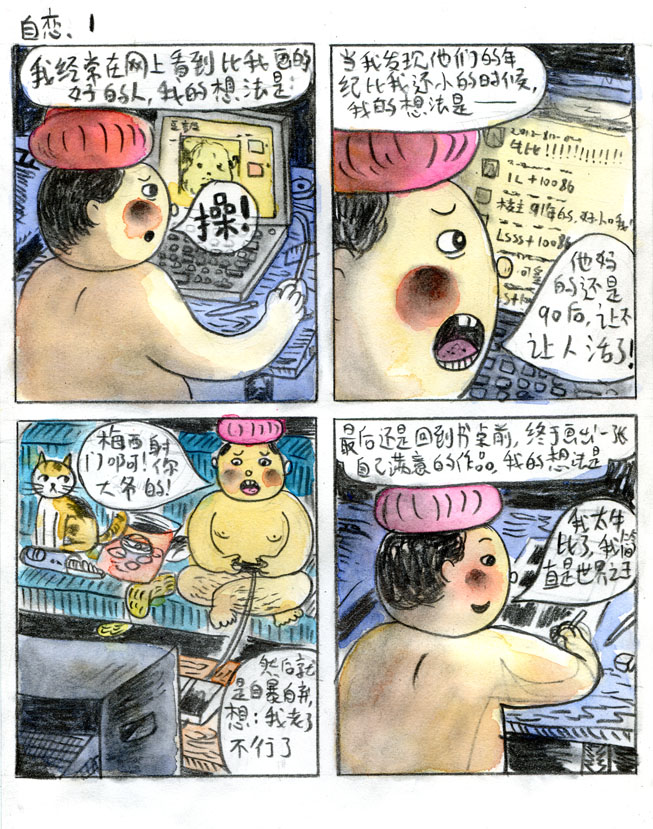

“Narcissism” by Yan Cong // 《自戀》 煙囪

In Chinese, manhua is a general term which refers to the global comics medium and therefore includes Japanese, Korean and American comics.4 One of the most interesting ways in which manhua is being created in this context today is the dixia manhua 地下漫畫, or ‘underground comics’ movement which is being spearheaded by artists such as Yan Cong 煙囪 and Chi Hoi 智海, who have helped organized the groups secret comics (aka SC 漫畫) in Beijing and Springrolllll in Hong Kong.

Context 3. Manhua as a historical tradition

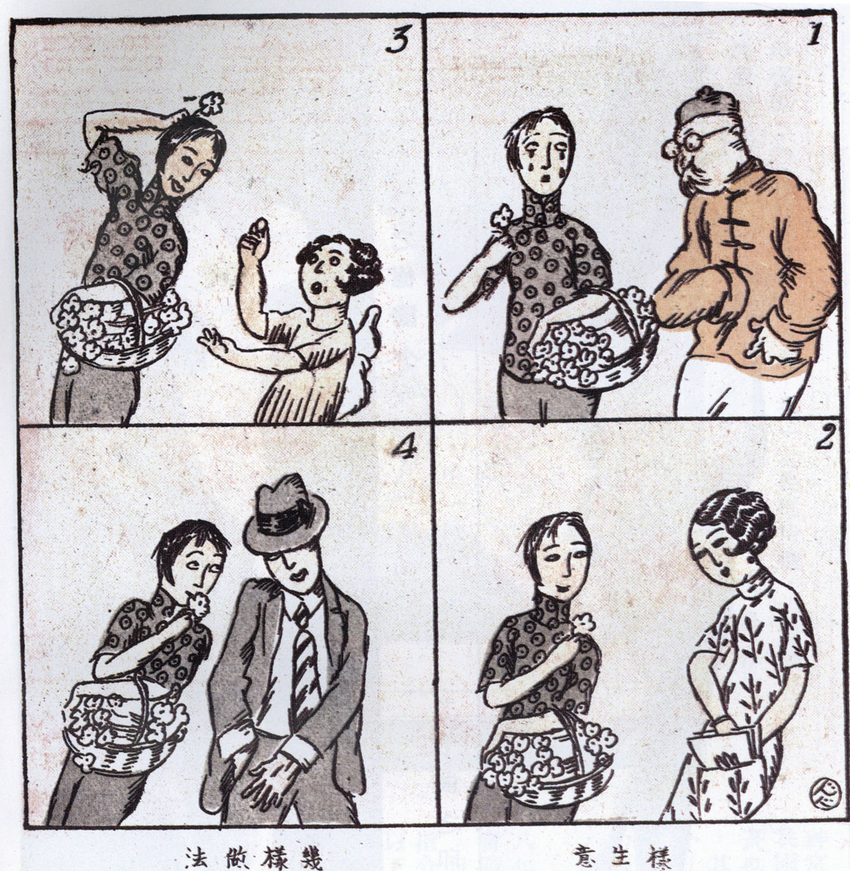

“Many Ways of Doing Business.” by Lu Shaofei // 《樣生意 幾樣做法》 鲁少飞5

A third way the term manhua is used is to describe the tradition of Chinese cartooning which is generally thought to have begun with the introduction of lithographic printing technology in the mid-nineteenth century in the foreign concessions in Hong Kong and Shanghai. The earliest comics (as defined by this definition) produced within China appear to be two satirical comics anthologies which were produced in English, The China Punch (1867–1868, 1872–1876) and Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari (April 1871-November 1872).6 Along with imported comics magazines from North America and Europe, these works would go on to inspire pioneering Chinese manhua artists such as Feng Zikai (1898-1975), Ye Qianyu 葉淺予(1907-1995), Zhang Leping 張樂平 (1910-1992) and Sapajou (? – 1949), many of whom spent the most fertile period of their careers creating anti-Japanese propaganda.7 Unfortunately, many of the early manhua artists such as Feng Zikai by and large stopped producing comics after 1949 due to the changed political climate.

Context 4. Other forms of Chinese visual narrative as manhua

Lianhuanhua adaption of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front8

A third way manhua is used is to describe Chinese forms of visual narrative which are similar to comics but are have not traditionally been described as such. For example, the comics scholar Paul Gravett has described lianhuahua 連環畫 (linked-picture books) as an indigenous Chinese form of comics.9 Other potential works which have been suggested include cave engravings, illustrated Buddhist sutras from the Tang dynasty, Song dynasty landscape paintings, and illustrated vernacular fiction from the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Context 5. Comics about China as manhua

“Captain China” Chi Wang and Jim Lai // 《中國隊長》 王家麒和黎寅祥10

Finally, and perhaps the most controversially, I believe the manhua medium can be said to include comics which were made outside of China, but deal with Chinese themes. For example, the Chinese-American artist Gene Yang works include extensive references to Chinese mythology and cultural practices, with his most recent book being set in Shandong during the Boxer Uprising and featuring an almost exclusively Chinese cast of main characters. Guy Delisle’s Shenzhen is another work which I believe could be considered to belong under this more tenuous definition of manhua. The most problematic works which be included in this definition are those which portray Chinese in a negative light and are based on stereotypes, such as the numerous Fu Manchu comics produced by Marvel and others. Still, I think there is value in looking at these works and their relationship with the larger body of Chinese comics outlined above, considering the amount of interplay which exists between American comics and manhua.

- Belonging the Chinese script, language and/or cultural context. [↩]

- Domestic being used in the economic sense here, as in ‘gross domestic product.’ [↩]

- This is often abbreviated to guoman 國漫. Manhua from Hong Kong and Taiwan seem to use more neutral terms such as bendi manhua 本地漫畫 (local comics) or bentu manhua 本土漫畫 (native comics) for Taiwanese comics in particular. [↩]

- Nowadays, it’s also less commonly used than the term dongman 動漫, a portmanteau of the Chinese words for animation, donghua 動畫, and manhua, similar to how someone might say that they like anime to describe an interest in both Japanese animation and also manga. Dongman also carries connotations of video games, as fans of one tend to be fans of the other. [↩]

- Shanghai manhua 11 July 1, 1928, reproduced in “Shanghai Manhua, the Neo-Sensationist School of Literature, and Scenes of Urban Life” Ellen Johnston Laing, MCLC Resource Center 2010 [↩]

- See Christopher G. Rea “‘He’ll Roast All Subjects That Might Need the Roasting’: Puck and Mr. Punch in 19th-c. China.” In Asian Punches: A Transcultural Affair. Hans Harder and Barbara Mittler, eds. Berlin: Springer, 2013. [↩]

- One major way these artists have influenced modern manhua creators is through the children’s animations produced at the Shanghai Animated Film Studio 上海美術電影製片廠 during the 1950s and early 1960s, and again during the 1980s. The head of the studio, Te Wei 特偉 (1915-2010) and his frequent collaborator, Hua Junwu 華君武 (1915-2010), both began their careers as cartoonists turned propagandists and later began making animated films at the behest of the Ministry of Culture in the newly formed PRC. [↩]

- From the Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College [↩]

- See this interview. Endymion Wilkinson would appear to agree with Gravett, having translated a collection of Communist lianhuanhua which was published in 1973 under the title The People’s Comic Book. [↩]

- Published in a bilingual English-Chinese edition by Florida-based Excel Comics, 2013. [↩]

Pingback: Chinese Lianhuanhua: A Century of Pirated Movies | Nick Stember