As many of you already know, I am on track to graduate from the Department of Asian Studies at UBC with my Masters degree in August. After a lot hand wringing, I’ve decided to take a year off from graduate school to devote myself to translation and other projects. I’m not sure if I will continue on to a PhD at the end of the year or not.

The good news: I’m still head over heels in love with Chinese comics, and plan to continue blogging and tweeting far, far into the foreseeable future. Here are the Chinese manhua and lianhuanhua that I plan to translate over the next six months to a year, depending other obligations (like eating, sleeping, paying the rent, etc) that life throws my way. Also, if you have any suggestions for future projects, or would like to donate to support my translations, there is a page for that now!

1. Smarty Pants Visits the Future 小靈通漫遊未來

Adapted by Pan Caiying 潘彩英 from the original 1978 story by Ye Yonglie 業永烈 with art by Du Jianguo 杜建國 and Mao Yongkun 毛用坤.

(Liaoning Fine Arts Press 遼寧美術出版社, May, 1980, 150 pages)

Description: Popular lianhuanhua adaptation of a groundbreaking post-Cultural Revolution sci fi story. A young boy visits the near future and learns about all of the amazing new technologies which will make life easier for the Chinese people, including smart watches, robot butlers, hover cars, and (of course) giant watermelons.

Think The Jetsons meets EPCOT as imagined by Deng Xiaoping.

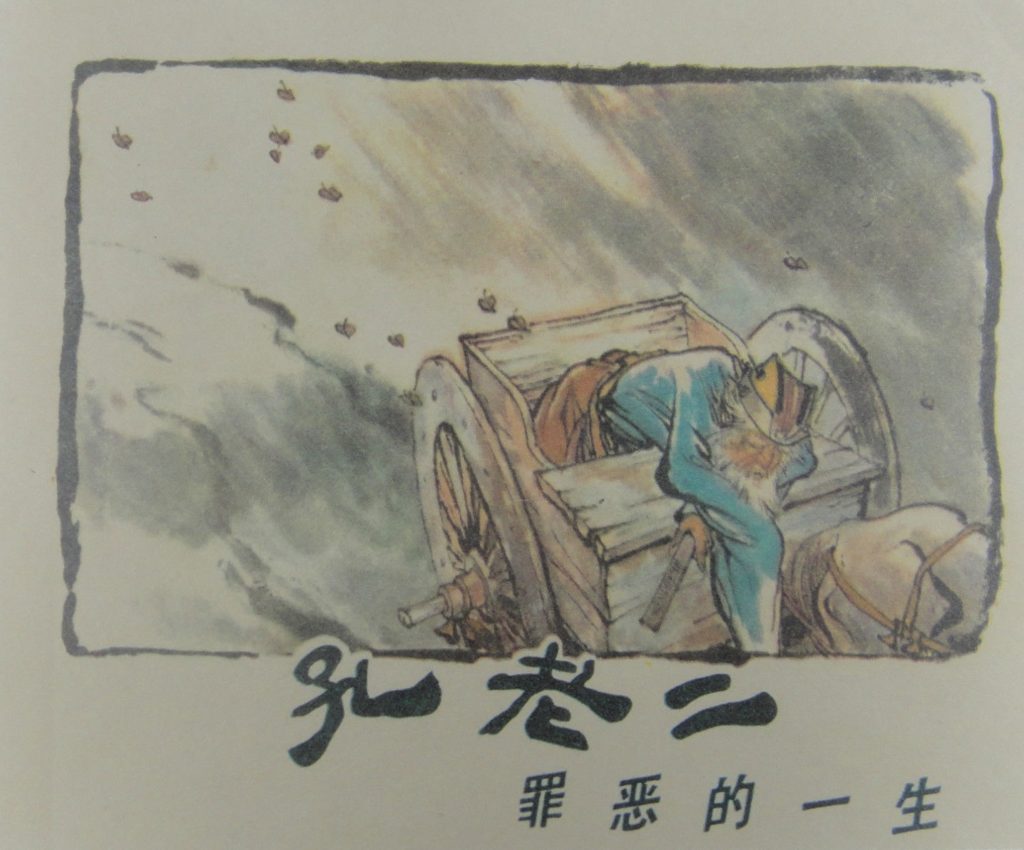

2. Confucius: A Life of Crime 孔老二 罪恶一生

Xiao Gan 萧甘 with art by Gu Bingxin 顾炳鑫 and He Youzhi 贺友直

(People’s Press Shanghai 上海人民出版社, June, 1974, 23 pages)

Description: This short comic was produced towards the end of the Cultural Revolution as part of the 1974 “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” campaign launched by the Gang of Four. Sharply critical of the ancient philosopher whose teachings (or interpretations thereof) have come to be seen as foundational to Sinophone countries, this irreverent look at the man from Qufu is one of the more light-hearted products of the disastrous Cultural Revolution.

Think O Brother Where Art Thou meets The Devil’s Dictionary as imagined by Christopher Hitchens.

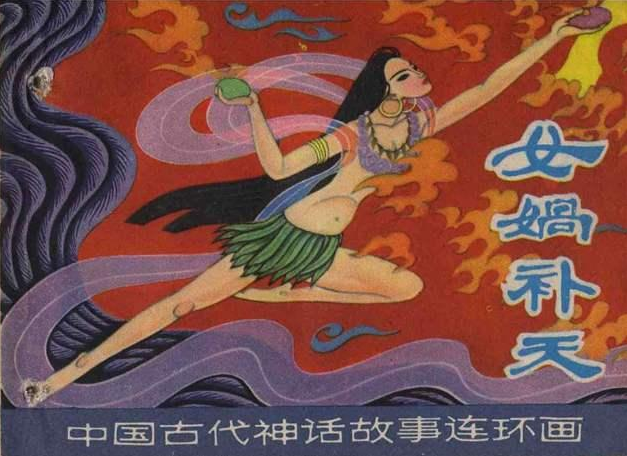

3. Nüwa Repairs the Heavenly Mantle 女娲补天

Adapted by Shi Jinglin 石景麟 from the original retelling by Yuan Ke 袁珂 with art by Hu Yongkai 胡永凱.

(Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Press 上海人民美術出版社, July, 1980, 65 pages)

Description: Lyrical retelling of the classic Chinese creation myth with incredible art by Hu Yongkai. Later made into an award winning animation by Qian Yunda 錢運達 at the Shanghai Animation Studio 上海美術電影製片廠, with art direction by Hu Yongkai. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, adaptions of traditional stories became a way for artists and authors to indirectly criticize the Gang of Four and the excesses of the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, these works introduced young people to a rich cultural legacy which had been suppressed for over a decade. For Chinese language learners, they are a great resource for people who want to a get a deeper understanding of Chinese culture than is generally available in most textbooks.

Think: The Book of Genesis meets Turtle Island as imagined by Carl Jung.

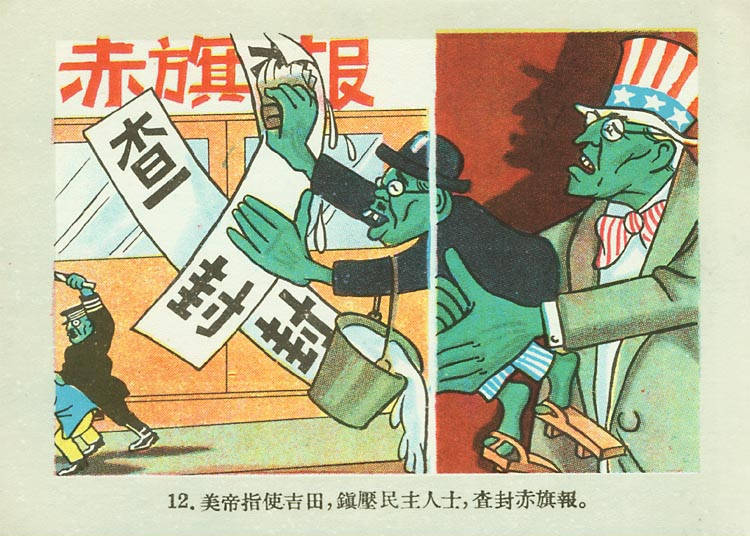

4. Pictures in Opposition of the American Imperialist’s Re-Armament of Japan 反對美帝武裝日本圖片

[or, for the sake of brevity, American Imperialism Exposed!]

Author unknown.

(Three People’s Press 三民圖書公司, 1950-52, 32 pages)

Description: These satirical postcards were collected by the OSS/CIA agent, journalist, and anti-communist crusader Edward Hunter (1902-1978) as part of the research for his book, Brain-washing in Red China: the calculated destruction of men’s minds (Vanguard Press, 1951). In recent years they have attracted some attention on various Chinese forums and internet media aggregators, thanks to their biting criticism of the US and Japan.

Think This is Tomorrow: America Under Communism! meets This Modern World as imagined by a socialist Thomas Nast from an alternate universe.

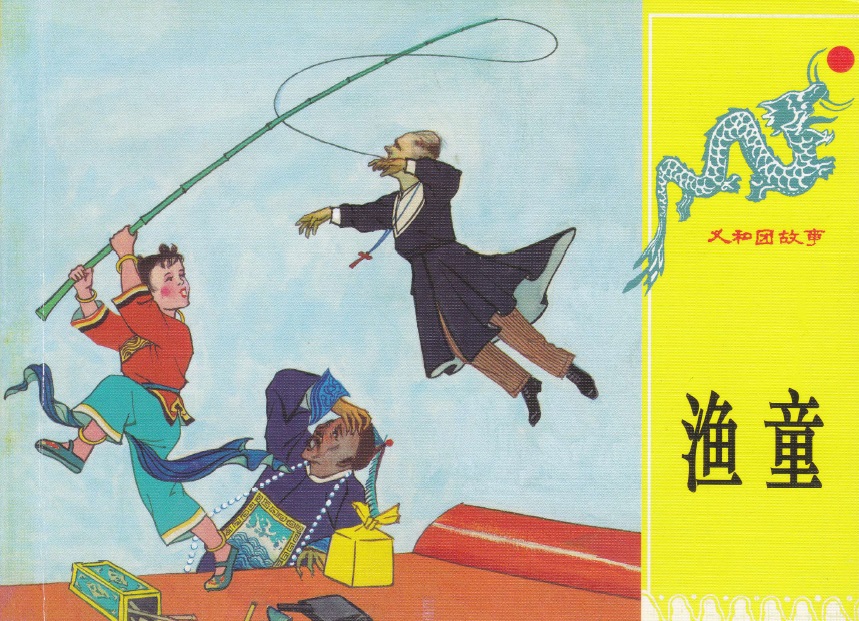

5. Fisher Boy 渔童 (Part of the Boxer Legends 义和团故事 series)

Adapted by Wu Chao 吴超 and Cheng Hua 程華 from the folktale collected by Zhang Shijie 張士傑, with illustrations by Bo Cheng 伯誠, Guang Yu 光玉 and Da Fang 達方.

(People’s Fine Art Press 人民美術出版社, July, 1959, 47 pages)

Description: This story was one of over a dozen collected and rewritten by the school teacher turned folklorist Zhang Shijie (1931-1978) in rural Hebei in the 1950s. In the story, the people of an unnamed fishing village find themselves in conflict with Western imperialists. An old fisherman finds a bowl emblazoned with an illustration of a “Fisher Boy” who comes to life to help the old fisherman. The magic bowl attracts the attention of a greedy Christian missionary and a corrupt Manchu official. Just when all seems to be lost, Fisher Boy emerges from the bowl to send his foes flying. By recasting (fictional) events which led to the (real) Boxer uprising as a nascent nationalism, folktales such as Fisher Boy played a critical and under appreciated role in cultural milieu of the PRC in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the story later being adapted not only into two seperate lianhuanhua, but also a children’s picture book and animated film. Due to the supernatural elements of the story, however, Zhang was denounced during the Cultural Revolution, and died in obscurity.

Think Peter Pan meets Captain Marvel as imagined by Karl Marx.

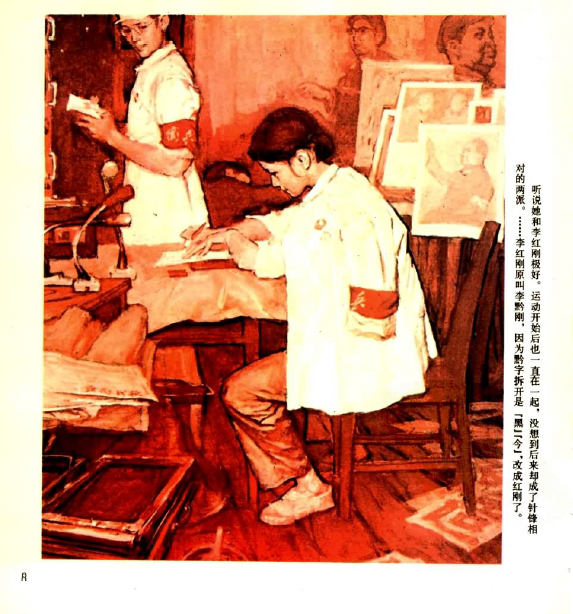

6. Maple 楓

Adapted and illustrated by Chen Yiming 陳宜明, Liu Yukang 劉宇康, and Li Bin 李斌 from the original short story by Zheng Yi 鄭義.

(Lianhuanhua Pictorial 連環畫報, August, 1979, 32 pages)

Description: A series of influential oil paintings, with text, depicting battles between opposing Red Guard factions during the Cultural Revolution. According the then editor of the Lianhuanhua Pictorial, Xu Mouqing 許謀清, this comic caused an uproar when it was first published. The frank depiction of the violence of the era and the strong emotional appeal are hallmarks of the Scar Art & Literature 傷痕藝術與文學movement which lasted from 1978 to 1982.

Think Mad Men meets Battle Royale as imagined by Alex Ross.

Support the Encyclopedia Manhuannica

As I mentioned above, I will be taking the next year off from graduate school to devote myself to translation and other projects. I have plenty of paid translation work (although I could always use more!), and so no matter what happens, I will continue to use my own money and time to translate and write about Chinese comics. I’d love to be able to devote even more time than I already do this site, though, which is part of a larger project to build the world’s first English language online reference book on Chinese comics, the Encyclopedia Manhuannica.

If you have an even a couple of bucks to spare, check out my Patreon site and consider pitching in so that I can keep putting up translations and high quality scans of Chinese comics for free!