The Tiananmen Square Massacre is an incredibly difficult topic to discuss without getting smeared with the brush of anti-CCP demagogue or, alternately, pro-CCP apologist.1 The modern Chinese historian Jeff Wasserstrom has argued that the term “Tiananmen Square Massacre” itself is something of a misnomer, given that most sources seems to agree that most (if not all) deaths occurred in the streets of Beijing rather than the square itself.2 Perhaps for this reason, the Chinese term is the much more neutral 6/4 六四, not unlike 9/11 in English. Meanwhile the iconic image of the Tank Man, together with student leader Chai Ling’s 柴玲 heart-rending (albeit unsubstantiated) account of seeing students flattened by tanks in the Square, has overshadowed the much more numerous deaths caused by PLA gunfire. Equally critical, is the fact that workers and inhabitants of Beijing stood up and were killed along with the students, and that Beijing wasn’t the only city which experienced massive unrest: Shanghai experienced worker strikes and student walkouts, as did Wuhan, Guangzhou, Xi’an, Nanjing, Chengdu, and likely other cities as well.3

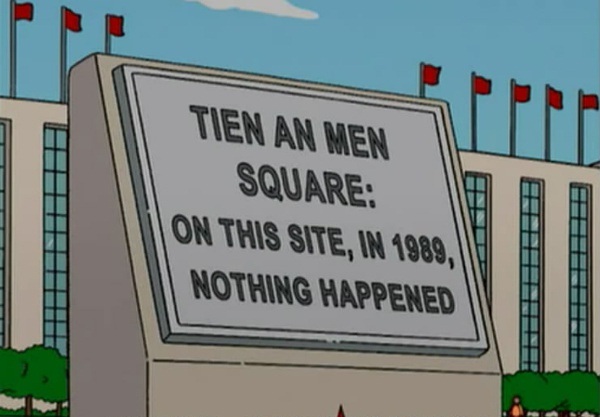

Unsurprisingly, the protests and crackdown remain sensitive topics in the PRC even today. More surreal, perhaps, is the fact that many younger Chinese know almost nothing about them and those that do often have little interest in discussing them:

This contrasts starkly with the situation abroad, where China is perhaps best known for the events of June 4, 1989. As a student of modern Chinese cultural history I find myself intensely conflicted about talking about 6/4. On the one hand, as a historian, I recognize that history should be a neutral, “true record” of events as they actually occurred, something which often conflicts with the desires of nation states and political parties to paint their pasts in the brightest colors possible. 4

On the other hand, as someone who is passionate about Chinese literature and culture, I often find myself frustrated with the extent to which the discourse on China is dominated by 6/4. Chinese literature in translation, in particular, seems to be almost singularly restricted to works which are “banned in China.”5 This leads to a very skewed perspective on Chinese popular culture in North America, which is in many ways every bit as vibrant (and trashy) as popular culture anywhere else in the world. Romance, horror, mystery, and sci-fi are all thriving, both on the internet and in bookstores. And even “serious literature” is thriving, too: two of the most popular novels in translation are 1984 and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And as Maggie Greene points out in her recent post on the surprisingly warm reception her Star Wars comic received on the internet last week, there have been other, earlier periods of “thaw” in censorship, particularly during early 1960s following the Great Leap Forward, and again in the 1980s, after the Cultural Revolution. 6

I think this is a much larger issue than just 6/4, one which can be traced back to Cold War. The communist takeover of China and the polarizing figure of Chairman Mao perhaps irrevocably connected China with socialist and totalitarian politics in the American imagination. Theodore H. White’s 1967 Emmy-winning documentary, China: The Roots of Madness is emblematic of this association, and of the desire to connect the man-made tragedies of the Mao-era with earlier cultural traditions in China:7

While the desire to understand the madness of the Cultural Revolution is understandable, blaming the excesses of radical Maoism on 2000 years [sic] of Confucianism is a little bit like saying McCarthyism was caused by the same Puritanical-thinking which led to the Salem witch trials. And while it might seem like this kind of thinking is far behind us, consider the the widespread belief that China isn’t “ready” for democracy or that Chinese people are incapable of creativity.8

That said, there are many accounts of 6/4 which do an excellent job of placing it in a larger historical context. I personally think autobiographical comics and animations are well suited to this purpose. Memory is incredibly subjective, and photographs have a tendency to seem much more objective than they often actually are. When we look at a drawing of a memory we are forced to acknowledge that memories are created and re-created over and over, rather than being preserved like fossils waiting to be unearthed.

1. Wang Shuibo’s 王水泊 Sunrise Over Tiananmen Square 天安門上太陽升

The visceral sense of the betrayal Wang Shuibo experienced after 6/4, having grown up in a “New China” where Mao was treated as essentially a demi-god and the CCP were his sacred protectors is palpable in Wang’s 1998 Academy Award nominated short animated film. This is something I have seen first-hand among my Chinese friends who seem to be angrier about the fact that the government continues to lie to them about the past than they do about the massacre itself, the impact of which has faded somewhat with the passage of time:

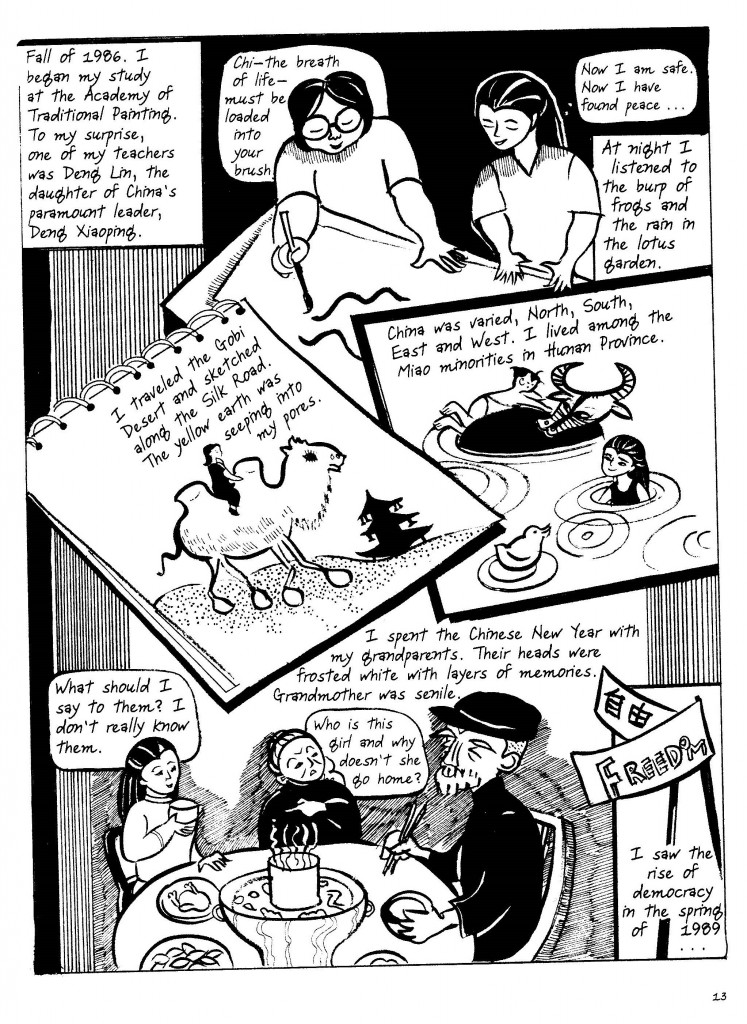

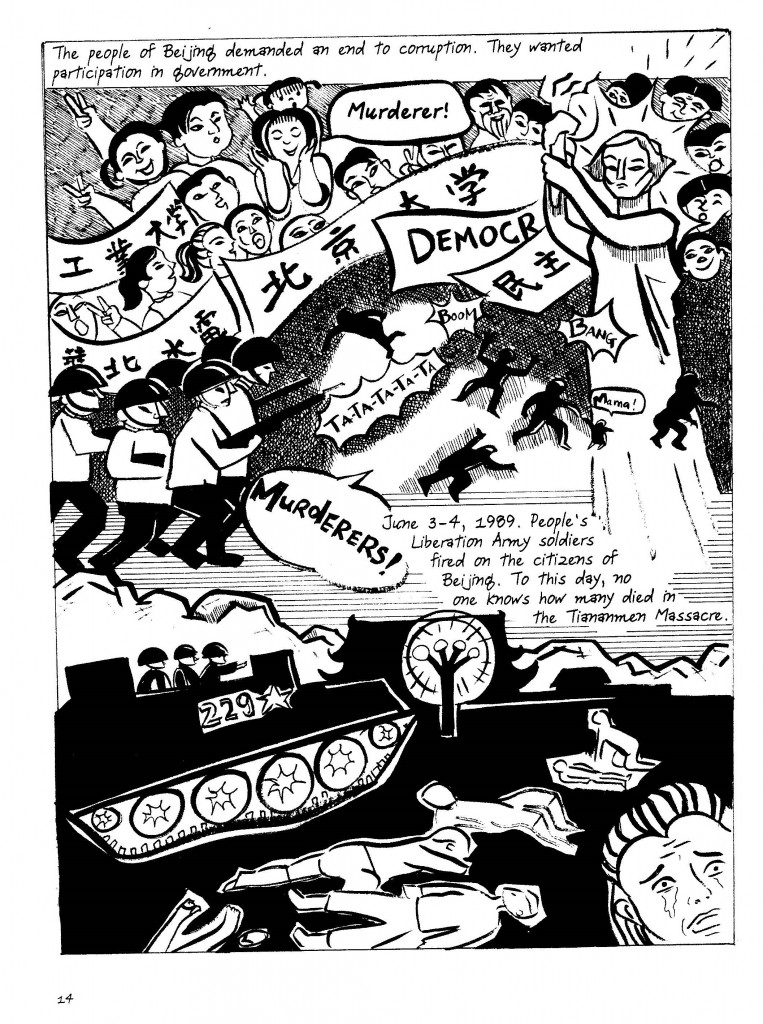

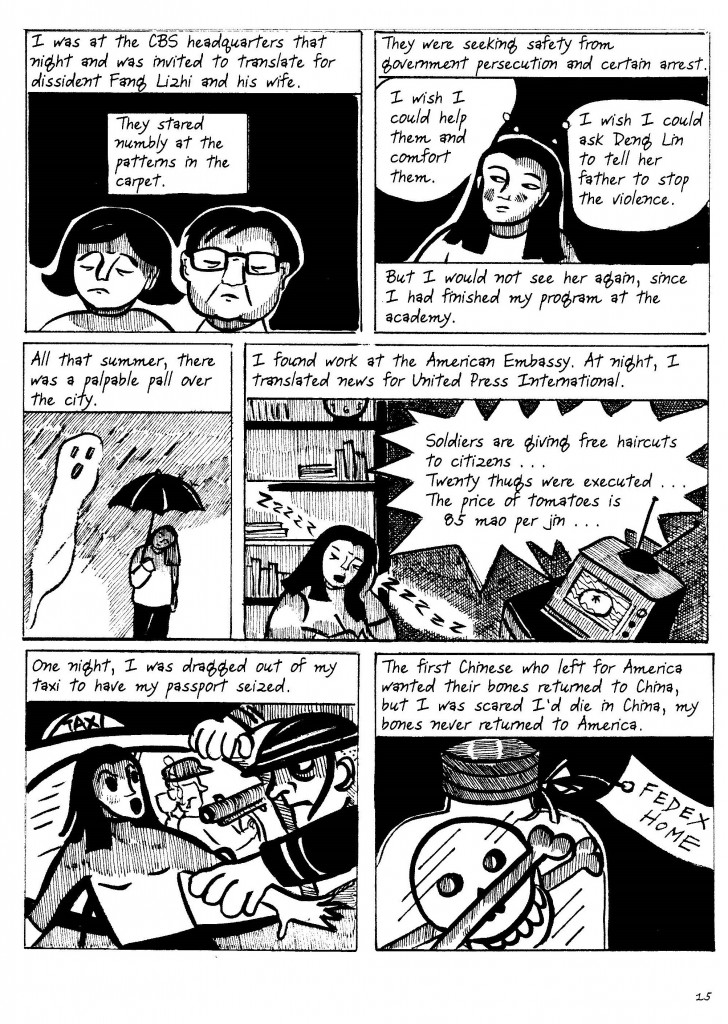

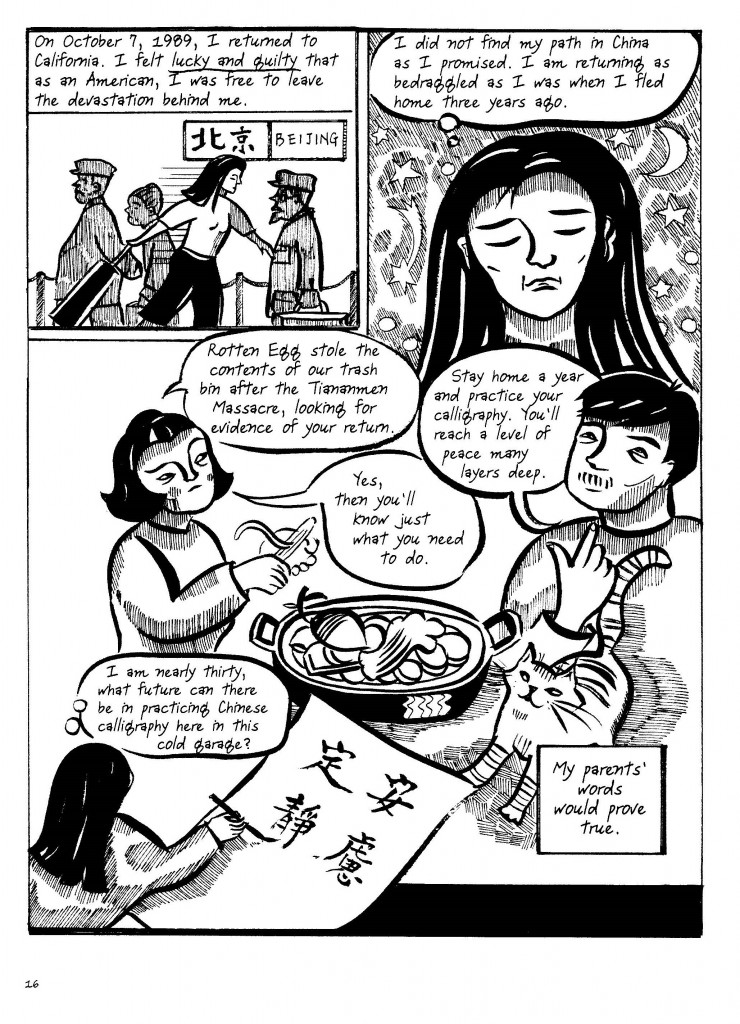

2. Bella Yang’s Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale

Bella Yang’s account of 6/4 plays a very small, but critical role in her graphic novel Forget Sorrow: An Ancestral Tale. After fleeing her home in the US due to threats by a violent stalker ex-boyfriend, Yang ends up studying art at the Academy of Traditional Painting in Beijing. This mirrors her father’s journey from Manchuria to the US in following the communist takeover/liberation of the Chinese mainland in 1949. Her studies are cut short, however, when the crackdown on the protests of 1989 leaves her shaken and afraid for her personal freedom:

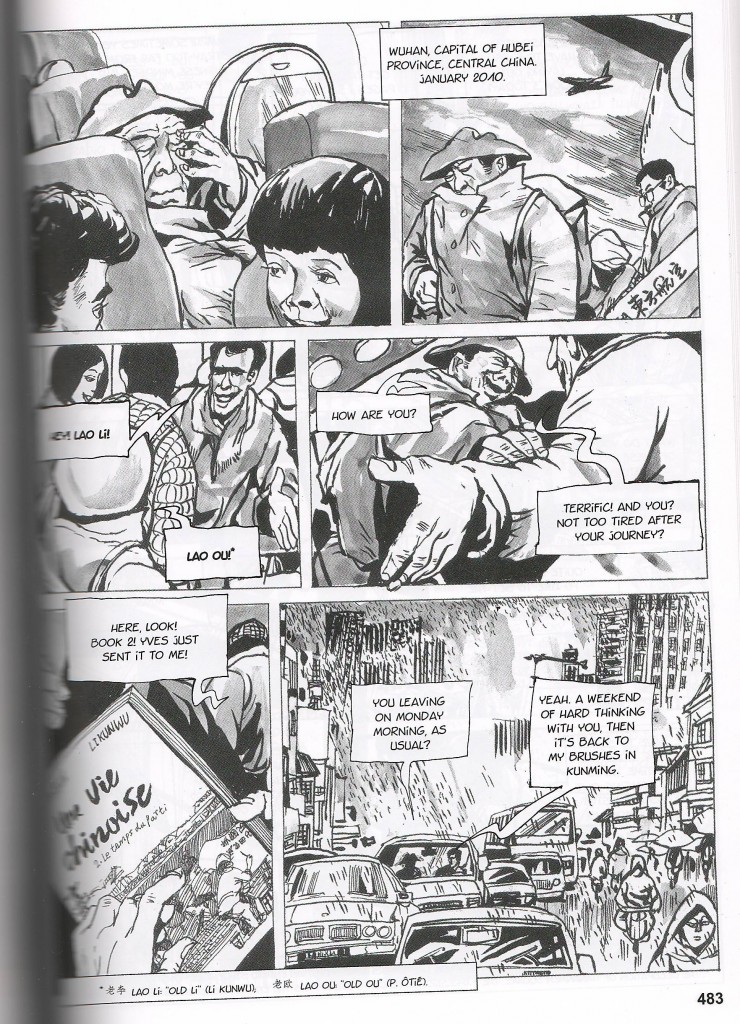

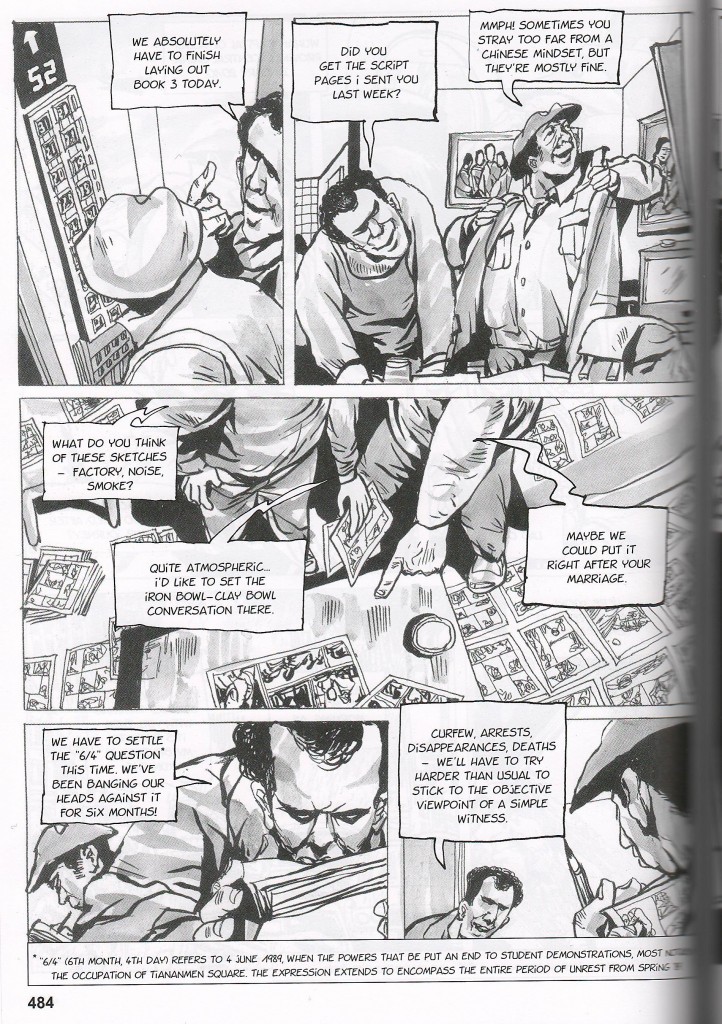

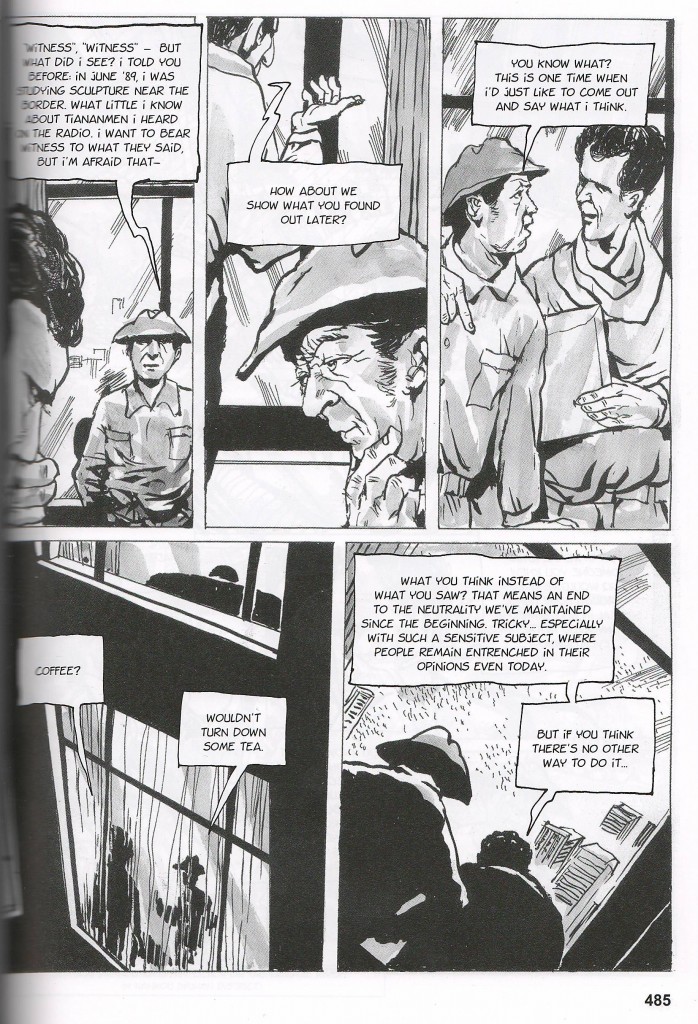

3. Li Kunwu 李昆武 and Philippe Ôtié’s Une vie chinoise / A Chinese Life 從小李到老李

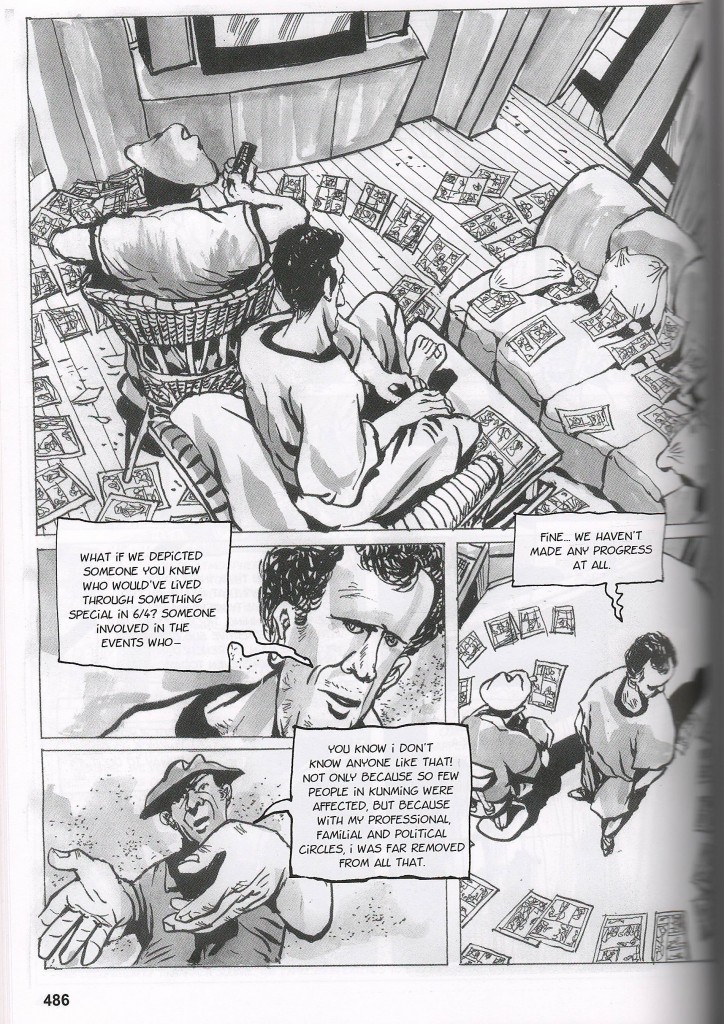

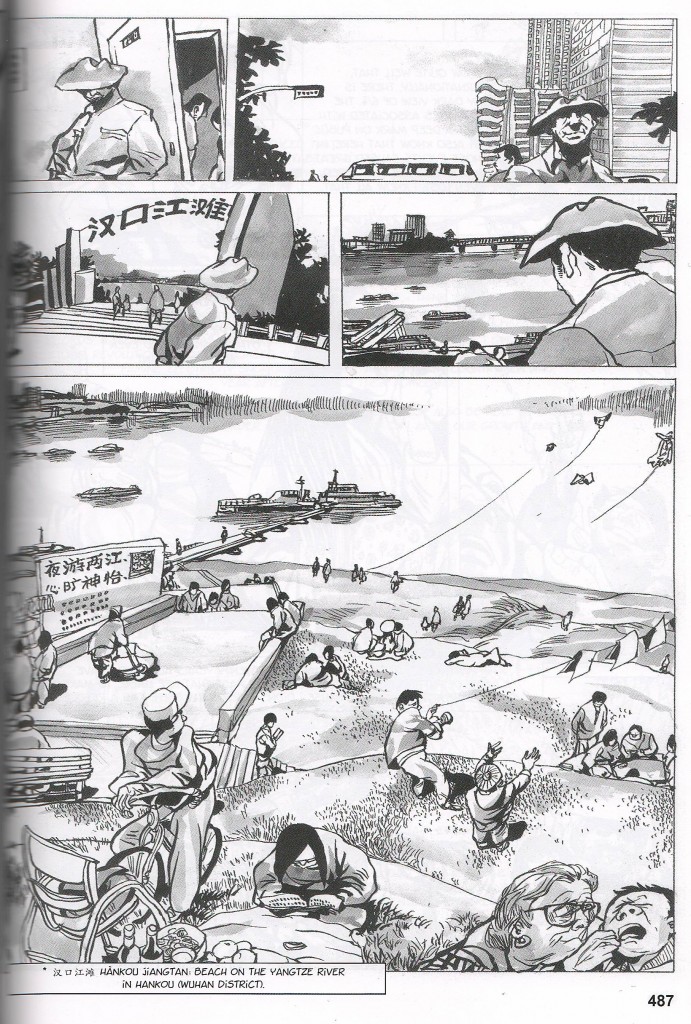

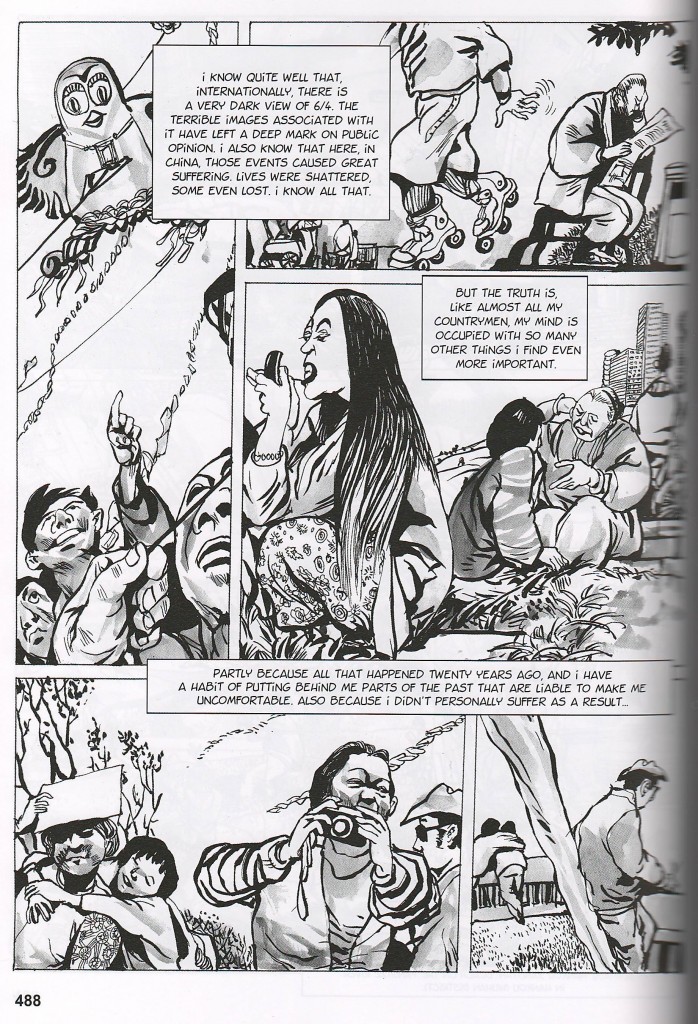

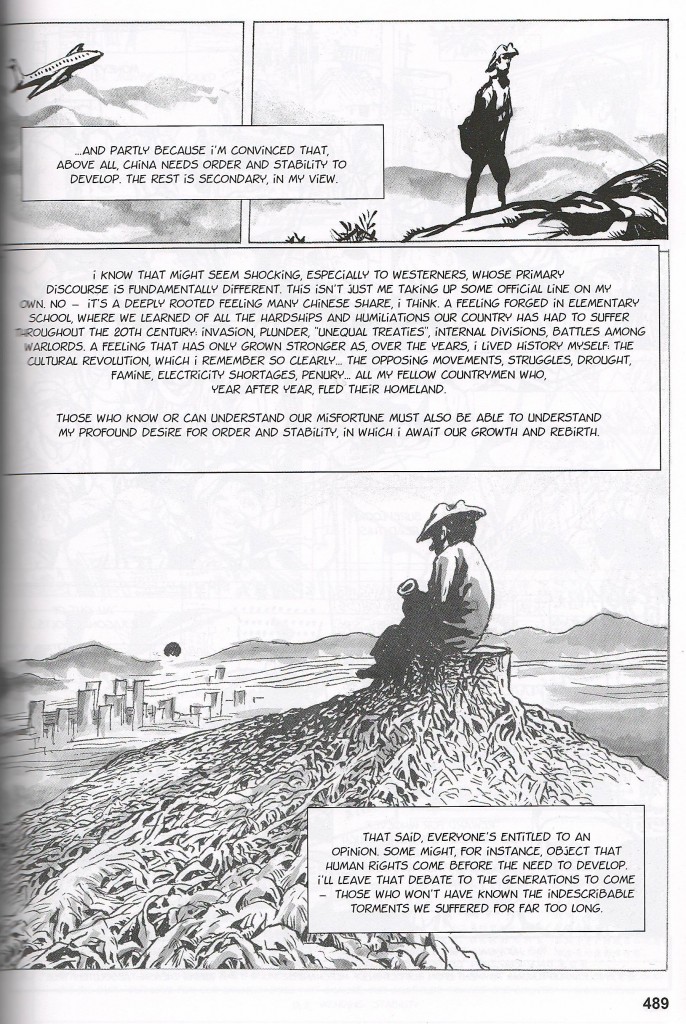

Perhaps the most interesting of response to 6/4 in comics is Communist Party member and former propagandist Li Kunwu’s A Chinese Life, co-authored with the French trade diplomat Philippe Autier (writing under the penname Philippe Ôtié) in 2010. This massive 600 page book took five years to complete, and was released with much fanfare in English translation in late 2012 by SelfMadeHero. To date it hasn’t much of a splash in the North American comics scene. Although I haven’t had a chance to read the Chinese translation, which was finally released in early 2013 and went on to win the Golden Dragon Award 金龍獎9 for that year, I am willing to bet the following passage in which Li and Autier argue about how to portray (or why not portray) 6/4 has been cut:

For a course on historiography in Asian Studies last year with Sharalyn Orbaugh, I wrote a seminar paper which centers around this passage in A Chinese Life. I’ve recently been invited to present a version of that research at the 17th International Comic Arts Forum in at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus, Ohio, Nov. 13-15. In my abstract for my paper I wrote:

My goal in writing this paper is two-fold: First, I would like to explore the ways in which the post-colonial experience of China is remembered by the generation of men and women who were born in the 1950s during the first decade of the People’s Republic of China by looking at Li Kunwu’s graphic novel, A Chinese Life (2005-2010), co-authored with Philippe Ôtié and translated into English (from French) by Edward Gauvin. In this book, Li describes his lived experience as the son of a communist cadre and villager from rural Yunnan, a teenaged Red Guard, a People’s Liberation Army propagandist and finally a cartoon journalist. This retelling is presented as a long series of mostly interconnected flashbacks occurring inside of Li’s head and is interspersed with short disjointed, depictions of the present. My second goal for this paper is to look at the ways in which the remembering of this history is complicated by the fact of being co-authored with a French writer and commercial diplomat and produced in cooperation with a French publisher. That Li Kunwu and his coauthor have addressed these concerns both in their book and also in interviews demonstrates the inherent impossibility of ‘true’ representation of marginal communities encapsulated in Giyatri Spivak’s haunting interrogation, “Can the sub-altern speak?” Foreigners and foreignness therefore play an important role throughout the novel, shaping the narrative in an overt and palpable way.

I think that the same can be said about the discourse around the June 4th Massacre: Foreigners and foreignness shape the discourse in an overt and palpable way. This is not to discount genuine expressions of sympathy for the victims of the massacre, or to excuse the perpetrators and apologists, but simply to say that we would not be interested an atrocity which occurred 25 years ago in another country if it did not speak to deeper fears about our own society and our tacit acceptance of state violence in other countries to guarantee our current standard of living.

I do hope that someday the events of June 4th, 1989 will be a topic of public debate in China. At the same time, I also hope that people in my own country will begin to engage with China on a deeper level than one we currently do.

- Or in non-academese, Panda Hater or Panda Hugger. [↩]

- In this this piece he wrote for the Huffington post for example, he refers to it as the “June 4th Massacre.” [↩]

- The website for the excellent documentary, Gate of Heavenly Peace, has a long list of publicly available resources: http://www.tsquare.tv/links/ [↩]

- Take, for example, the way the historical repression of organized labor has been pushed out of American classrooms in favor of subjects such as the Civil Rights Movement and WWII. [↩]

- The interest in “forbidden fruit” is also equally true for Chinese readers, of course: http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2013/07/19/hong-kongs-banned-book-fair-is-big-hit-with-mainland-chinese/ [↩]

- And, of course, there were equivalent periods during the Republican-era and the late-Qing and other earlier dynasties, as well. [↩]

- For a great take-down of this awful, awful film, see http://www.filmthreat.com/features/22523/ [↩]

- Admittedly, Chinese writers themselves are often the most vocal proponents of such theories. [↩]

- Awarded annually at the Golden Dragon Award Original Animation & Comic Competition 金龍獎原創漫畫動畫藝術大賽, the Golden Dragon Award appears to be one of the highest honors available to a Chinese-language comic, equivalent to the The Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards in North America, or the Angoulême International Comics Festival Awards in Europe. Since 2003, it has been co-organized by the comic book publisher ComicFans 漫友, the General Administration of Press and Publication 国家新闻出版广电总局, and the Guangdong Provincial People’s Government 广东省人民政府 and takes place at the International Comic Book Festival 中国国际漫画节 in Guangzhou. Somewhat confusingly, there is also a Golden Monkey Award 金猴獎 which has been awarded at the China International Cartoon and Animation Festival 中國國際動漫節 in Hangzhou since 2004, and the (apparently defunct) Golden Comic Award 金漫獎 organized by the Ministry of Culture in Taiwan 中華民國文化部 in from 2010 to 2013. [↩]

Pingback: Tiananmen at 25: Massive Reading Round-Up, June 3 Edition | Maura Elizabeth Cunningham